Liu Jinsong sits behind the counter at the maternity shop he opened 20 years ago in central Beijing, under racks of expandable jeans and leggings, waiting for customers. Mostly, he just waits.

“Our business has been decreasing so much,” he sighs, crossing his knees. “Before we did wholesale and sold a lot. Now business is really slow.”

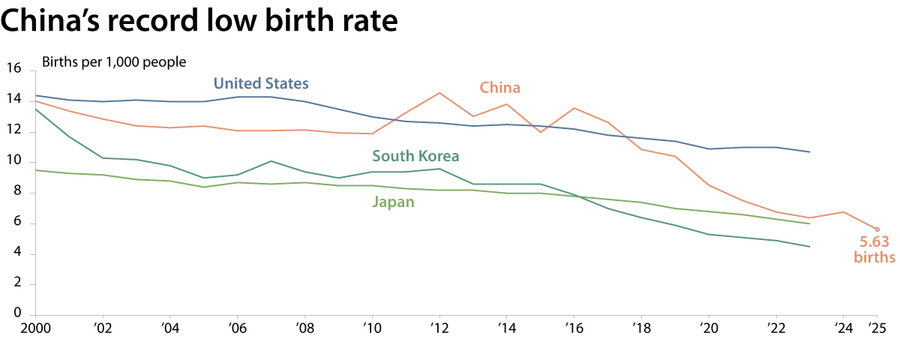

China’s birth rate hit a record low in 2025, despite a raft of government measures in recent years aimed at encouraging couples to have more children.

Why We Wrote This

Despite Beijing’s campaign to encourage couples to have more children, new data shows China’s population decline is accelerating. Some experts believe the problem lies in the government’s narrow, materialistic approach to family planning.

The number of births per 1,000 people plunged to 5.6, the fewest recorded since the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, national statistics released last week show. About 7.9 million babies were born in China last year, significantly fewer than the 9.5 million born in 2024.

The sharp reduction suggests China’s pronatalist agenda is proving ineffective, demographers say, and the country is following the pattern of the rest of East Asia – the region with the world’s lowest fertility rates.

“The decline in scale and speed was even faster” than predicted, says Yong Cai, associate professor of sociology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, who focuses on China’s birth policies.

China is likely undergoing “a large shift” that will see “a sizable number of women … stay single and child-free for their lifetime,” Dr. Cai says.

Delaying families

The reasons underlying the shift are complex, but include women’s empowerment, economic pressures, and gender gaps in the population exacerbated by China’s infamous, decades-long one-child policy.

As women make gains in education, social status, and independence, they are delaying or forgoing marriage. It is harder for them to find suitable partners, especially as most Chinese women seek to “marry up,” says Dr. Cai. The country has a large cohort of less affluent men, who face difficulty finding wives, he adds. Indeed, marriage in China is also an expensive proposition, with men expected to own a home and offer gifts to parents of the bride-to-be, and China’s slowing economic growth and high youth unemployment has made these conditions more difficult. And marriage is virtually a prerequisite for having children in China, as in other East Asian countries, given a long-standing taboo on out-of-wedlock childbirth.

The trend of delayed marriage and childbirth has reduced China’s total fertility rate (TFR) – or the average number of children a woman is expected to have in her childbearing years – to an estimated 0.98, slightly less than the 1.0 TFR reported for 2023.

As the population shrinks and ages, China’s government is making an all-out push to boost births. Policies include tax breaks, lump-sum payments or monthly allowances distributed by local governments to parents, as well as a national program offering 3,600 yuan (about $516) in annual child care funds for each child under the age of three, introduced in 2025. The government also removed an exemption to allow tax on the sale of condoms and other contraceptives.

But the top-down, sometimes heavy-handed approach that emphasizes monetary incentives is having little impact – and could even be backfiring, experts say, as it reminds the public of the intrusive one-child policy.

The right messaging

“The message right now is all about the cost-benefit calculation,” says Dr. Cai. “My criticism is … people are not going to have kids for the sake of a few extra hundred dollars. … The thinking is too materialistic.”

Indeed, so far there are few indications such incentives are working. In the 10 years since China lifted its one-child policy in 2016, its number of annual new births has fallen 40% and the number of new marriages has plunged 50%, according to a report by Gavekal Dragonomics, a research firm focused on China’s economy.

As a result, China’s TFR now matches the average for East Asia, or about 1.0. Within the region, South Korea has the lowest TFR at 0.72, as of 2023, and Japan’s is marginally higher than that of China, at 1.2.

“These numbers are considered ultra-low fertility that have profound implications for population age structure,” says James Raymo, professor of sociology at Princeton University, who researches demographic trends in Japan.

As a comparison, the United States’ total fertility rate is around 1.6. A rate of 2.1 is needed for replacement of the population.

China’s policy approach is unrealistic in that it is aimed at persuading people to have more children, rather than supporting people in being able to have the number of children they want.

“Exhorting people to give birth for the country is delusional,” says Dr. Raymo, who argues that policymakers must “think holistically about building a social and economic environment in which people can realize their desired family structure and size.”

And that lesson is all the more important as most developed countries, from Canada and Argentina to Germany, are well below the 2.1 TFR mark. United Nations forecasts show the global TFR could drop to 1.8 by 2100.

“What’s happening in East Asia is a sign of what’s coming for most of the world,” Dr. Raymo says.