This article is taken from the June 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Ben Cobley has written a good — I dare say a necessary — book. It could have been an even better one. The author subjects the “progressive” mind to a harsh scrutiny, in the course of which he reveals much of the received wisdom of our day as neither wise nor willingly received. But he is less illuminating on the ideas that have animated progressive thought over the past two centuries — above all, of course, the idea of progress itself.

Not that Cobley intended to write an intellectual history of progressive movements or indeed a work of scholarship of any kind. The Progress Trap is a polemic against the foes of its subtitle: “The Modern Left and the False Authority of History”. And an excellent polemic it is, too.

In one blast after another, Cobley slays the dragons of decolonisation, the Hydra of historical destiny, the Scylla of morality as sociology. He exposes the tactics of progressivism: the hegemony of experts, the appropriation of divinity, the hostile takeover of capitalism. He shows how the ubiquity of identity politics creates a social hierarchy that advances the progressive agenda. He explains how the technocratic state generates a self-righteous bureaucracy, which enforces compliance in the public services and is squeezing the life out of the rest of us if we try to resist it.

If this twilight of the progressive idols sounds slightly exhausting, that is because Cobley takes no prisoners. The Progress Trap would be more persuasive if its hectoring tone of j’accuse! were less relentless. Swift’s Modest Proposal and Voltaire’s Candide are both satires aimed at progressives avant la lettre. That they are still read today is, however, solely thanks to the admixture of irony, mockery and grotesquerie.

Instead, the author constantly belabours his opponents with the blunt instrument of totalitarian comparisons. Mao, Stalin and Hitler are all freely invoked, as though online ostracism or “cancellation” were the equivalent of physical liquidation in the gulag. Our “culture wars” are not remotely akin to the Cultural Revolution. The Führer would have been surprised to learn that “Hitler’s thinking has strong parallels with progressive politics”.

Such exaggeration may be a pardonable display of youthful exuberance, but there’s a deeper problem with the book. In homage to Newton’s Third Law of Motion (“to every action there is an equal and opposite reaction”), Johnson’s law of politics states that “to every activist movement there is an equal and opposite reactionary one”.

Whilst the progressive hardliners richly deserve their comeuppance, Cobley’s critique does not confront the economic havoc, ideological vehemence and crude violence of the backlash they have provoked. By not taking the reactionaries either literally or seriously, The Progress Trap is already out of date.

It is true that Cobley mentions Trump a few times in his final chapter, with a nod to Farage. But this is in the context of “How should we respond?” The “we” here is assumed by the author to be readers no less appalled by progressive triumphalism than he is. Much is made of the discomfiture of the wise fools who assumed Trump could not return to the White House.

But I suspect that most of those reading this review are just as worried that our erstwhile protector is now a predator who claims that he runs the world. People usually become conservatives because they have something to lose, and anyone who has investments has lost a great deal since the MAGA crowd moved in.

Mark Carney, the new Canadian prime minister, may be a smug progressive, but I’d trust him with my money rather than the lunatics who have taken over the asylum that the White House now resembles.

And yet Cobley treats Trump, too, as “a progressive of a different kind”. He divides progressive theories into two kinds: open and closed, or “progress as freedom” and “progress as power”. The open kind embraces liberals, social democrats and many conservatives in the West, who believe they are on the right side of history but are willing to accept that things may not turn out as they expect.

Closed progressives range from trans fanatics and social media narcissists to Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping. Woke progressives are, as Cobley demonstrates, adept at exploiting open societies to close down opposition to their particular cause. They are at the very least a nuisance and, when they cannibalise our culture so that younger generations are disinherited, far more than that. But it is the man of destiny who believes in the inevitability of his own apotheosis that should keep us awake at night.

This is where the fabric of The Progress Trap begins to fray at the seams. If the American President and the American Pope are both “progressives”, then we need a different terminology. Otherwise we fall foul of Hegel’s “night in which all cows are black”.

After the Reform UK landslide in the local elections, Cobley tweeted: “As soon as the reactionaries start doing well, they become progressive.” It’s true that some of Nigel Farage’s statist policies have been associated with the left, rather than the right. But this doesn’t make him “progressive”. Dame Andrea Jenkin, Reform’s new Mayor of Greater Lincolnshire, summed up the party’s aim succinctly as a “reset to Britain’s glorious past”. They are reactionaries, and Kemi Badenoch’s Tories are not. This is a fundamental distinction.

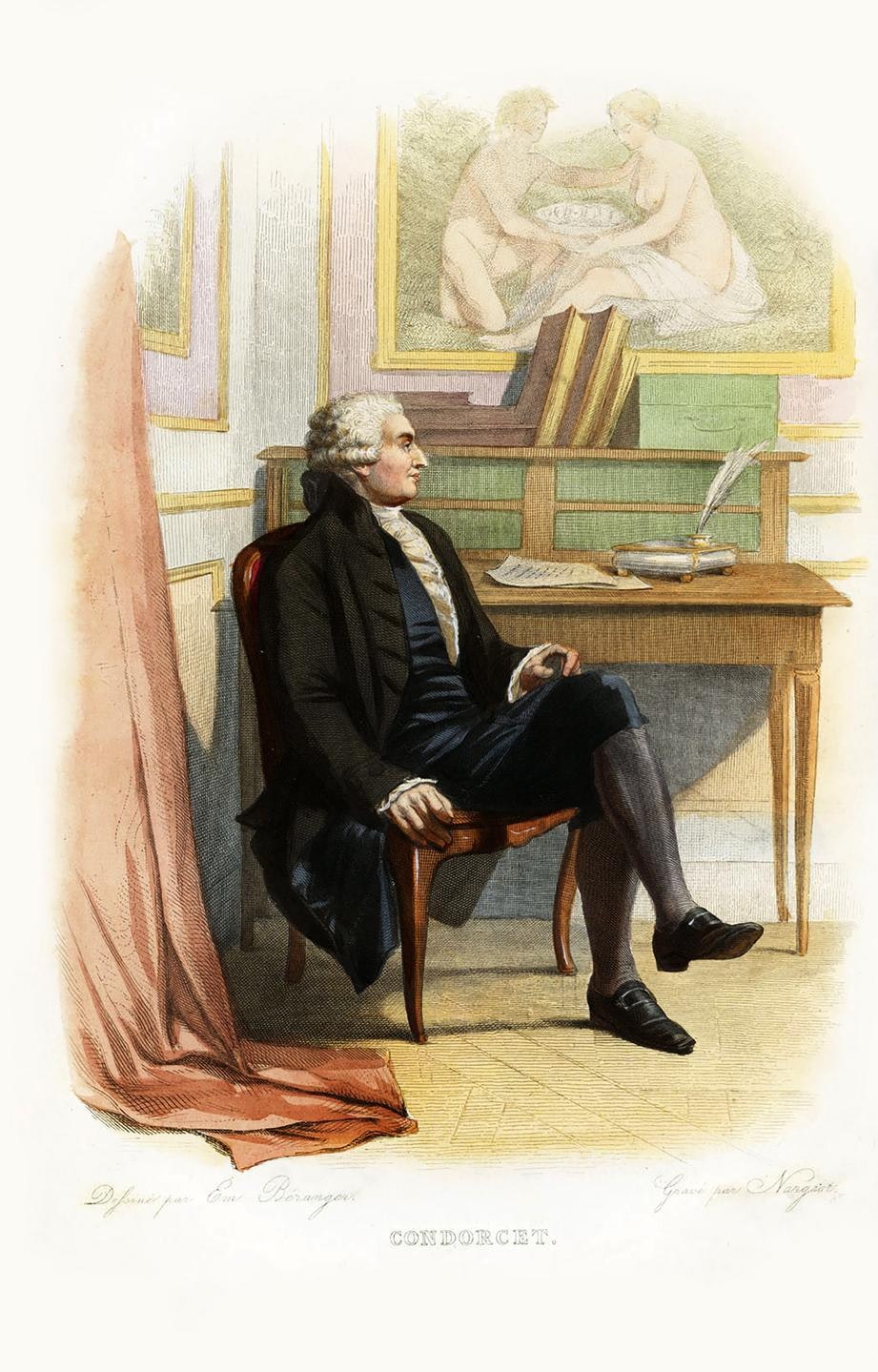

Let us return to the sources. The thinker we have to thank for the elevation of “progress” into the telos of history was Nicolas de Caritat, Marquis de Condorcet (1743–94): mathematician, social reformer and political philosopher. His Esquisse d’un tableau historique des progrès de l’esprit humain was published posthumously in 1795 and immediately gave the idea of “progress” a vogue which has endured ever since.

Cobley mentions Condorcet but only in the same breath as Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He doesn’t explain that these two luminaries of the Enlightenment represent opposing sides of the debate about progress.

Rousseau was deeply pessimistic about the advance of civilisation, and he has plenty of disciples today who hark back to a mythical golden age. Condorcet was adamant that progress was a blessing for humanity: it was based on the rise of what we would call the knowledge economy, embracing natural, moral and political sciences.

Condorcet predicted ten historical stages, but these were purely speculative and can be safely ignored. His Sketch was, as its title implies, drafted at high speed by a fugitive from the revolutionary secret police. Yet his outline of a free and democratic society with equal rights and duties has influenced posterity — so much so that we are still unwittingly in thrall to his vision.

Condorcet’s key idea is that history is driven by the progress of reason and knowledge. The history of humanity is the history of its emancipation from the bondage of ignorance. The term “progressive” should surely be reserved for this tradition, excluding those who also claim that history is on their side but have entirely different goals.

Admittedly, some of those who proudly proclaim their progressive credentials don’t measure up to Condorcet’s ideals. The Marquis himself was denounced by Robespierre and would certainly have gone to the guillotine if he had not died shortly after his arrest. In America, the original progressive movement, which counted Teddy Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson amongst its supporters, was associated with, amongst other obnoxious things, racist and eugenicist laws. Today’s woke progressives are no less intoxicated by their own self-righteousness, as Cobley so eloquently shows.

Yet Cobley himself concludes by reinstating progress as an ideal. He asks: “Would discarding the assumption of progress perhaps open the way for actual progress?” Invoking the false authority of history is not the same thing as doing justice to what Max Weber called the demands of the day.

Conservatives should reclaim Condorcet’s tradition, which belongs to them no less than to liberals. They too may echo Martin Luther King: “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

Bad ideas often adopt a progressive guise, but the appeal of human self-improvement is evergreen. Progress is too important to be left to the progressives.