Police have launched an urgent probe into the practices of surgeons at a hospital in Yorkshire, following the death of 11 patients after routine heart operations.

The BBC said today documents suggest that patients treated at Castle Hill Hospital suffered avoidable harm—which medics failed to disclose on their death certificates.

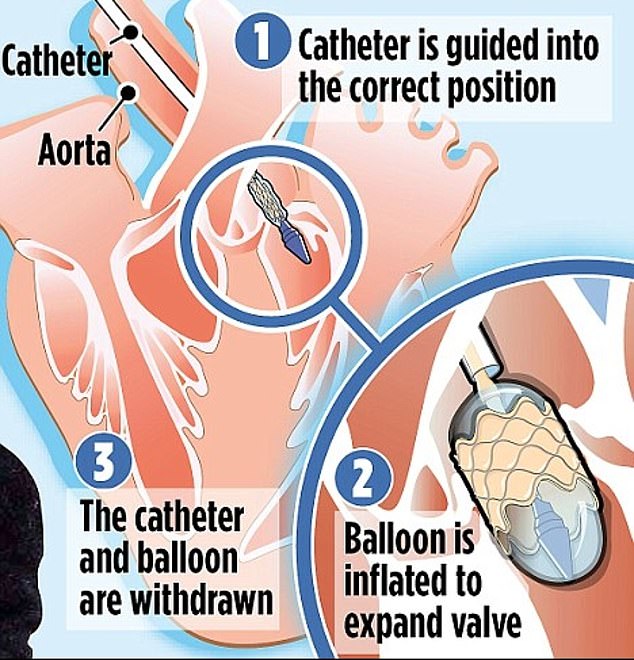

The documents raise alarm bells about the care of patients who underwent surgery for a transcatheter aortic valve implant (TAVI)—a common procedure to replace a damaged valve.

This operation usually takes around two hours, but one woman spent six hours in surgery, over the course of which she lost five litres of blood under local anesthetic.

Her procedure has been described as a ‘disaster’.

This ordeal was not mentioned on her death certificate, which simply stated she died of pneumonia. Her family were also not informed of the complications.

The police investigation is still in the very early stages and no arrests have been made.

After staff raised concerned that the department’s TAVI mortality rate was scarily high—three times that of the UK average—managers commissioned reviews to try and work out what was going wrong.

TAVI, first performed on the NHS in 2007, is safer and less invasive than conventional surgery, but often more expensive. For this reason, it is reserved for older patients deemed too frail to survive open heart surgery

These details were not made public at the time, with patients completely unaware of the alarmingly high mortality rates.

In 2020, the Royal College of Physicians led a department-wide investigation, in which the TAVI team was operating, following the death of two patients.

A year later in 2021, seven cardiac consultants said that they were ‘very concerned about the safety and transparency of the TAVI service’, in a latter to the hospital’s chief executive—following the death of four more patient in less than six months.

A third review into the death of all 11 patients involved was completed early last year—revealing the chilling mistakes of the surgeons involved.

The review criticised the medical team’s ‘clinical decision-making’ at every stage of the treatment of a 74-year-old patient and also found that crucial details were missing on the death certificates of a number of patients.

The TAVI procedure is most commonly performed on older patients, who have been deemed unsuitable for open-heart surgery.

The procedure involves inserting a replacement valve via a catheter through a blood vessel, usually in the upper leg or chest.

The catheter is then used to guide the replacement valve over the top of the damaged one. This is usually performed under local anesthetic—meaning the patient remain conscious.

The review also flagged how no mitigation had been made for a female patient, 84, who had an elevated risk which led to a complication ‘that may have been avoided among more experienced operators’

The technique has been shown in multiple studies to be both safe and highly effective.

Dorothy Redhead, 87, from Driffield, underwent the surgery in summer 2020, having complained of breathlessness which doctors put down to a heart condition.

According to her daughter, Christine Rymer, Ms Redhead had hoped that it would give her a better quality of life, as a keen gardener and active member of the community.

But, the operation was a ‘disaster’, ultimately resulting in her death just one week later.

Pre-operation checks indicated that Ms Redhead had a blocked artery in her right leg, meaning that the catheter should have been inserted into the left.

The manufactures of the TAVI device also agreed that access via her right artery was unsuitable.

But, on the day of the procedure, medics wrongly inserted the catheter into the patient’s right leg. Instead of stopping at the blockage, when they realised their mistake, medics tried to push the TAVI into her heart three times.

This error put significant strain on the 87-year-old’s body, and tore her femoral artery—a major blood vessel in the thigh.

Patients who undergo open-heart surgery typically remain in hospital for seven days, while those who receive TAVI leave within just three

At this point, Ms Redhead had been on the operating table for six hours, losing a dangerous five litres of blood.

An anaesthetist who was called in to help said that the team’s mistake and subsequent decision to continue with the procedure ‘resulted in a disaster’.

‘A completed change of plan without weighing the risks vs benefits for the patient, but having a ‘have a go’ approach because they can salvage a damage surgically almost did this patient in’, the anaesthetist continued.

However, the vascular surgeon on Ms Redhead’s case disagreed that this was a ‘serious incident’.

‘I see no grounds for this to be decaled an SI’, the surgeon wrote. ‘These were recognised complications which were anticipated as of significant risk’.

However, the hospital decided to go ahead with the investigation. They initially found that the team had worked well, and decided that whilst Ms Redhead’s death provided areas for improvement ‘these would not have prevented the incident from occurring’.

Ms Redhead’s family were not informed of the complications and her death certificate also made no mention of the procedure.

Her cause of death was listed as ‘hospital -acquired pneumonia and severe aortic stenosis’—the condition that Ms Redhead was referred for.

However, the Royal College of Physician’s report strongly disagreed, stating that the TAVI procedure led to the patients death .

Ms Redhead’s daughter, who was unaware of what her mother had been through told the BBC: ‘None of that was told to us. None of it.

‘It just feels as if mum was a guinea pig, which is not nice to think about’.

The most recent report looked at 11 cases in total, all linked to disasters on the operating table following a TAVI procedure.

Ten of these deaths occurred between October 2019 and March 2022, with the remaining death in May 2023.

Highlighting one death, the consultants—who had previously raised the alarm about the safety and transparency of the TAVI service—said they had been ‘alarmed to read’ that the coroner had not been informed of a serious complication during the operation.

The cause of the death was recorded as a heart attack.

After raising concerns about Ms Redhead’s death, Dr Thanjavur Bragadeesh, the clinical director of the cardiac unit, was asked to step down as part of a wider leadership reshuffle.

He told the BBC that the failures identified in the probe show he was ‘right to raise concerns about the TAVI procedure.

The Humber Health Care Partnership – which runs the hospital – said: ‘We understand families may have questions and we are happy to answer those directly.’

According to the BBC, mortality rates for the unit remain above the UK national average, despite the hospital making improvements following the report.