This article is taken from the June 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

The French don’t like to remember defeats. There is a running joke in Asterix and the Chieftain’s Shield, in which everyone vehemently denies the existence of Alesia, where Vercingetorix surrendered to Caesar. In the cavalry museum in Saumur the only mention of Waterloo in a fine exhibition on Napoleon are a couple of sentences in the last cabinet marked “other campaigns”. And no one knows much about the first winner of what we now think of as the French Open tennis championship in 1891. Perhaps because he was British.

We know his surname and initial because that is on the honour roll at Roland Garros, where the tournament is now played, and that H Briggs was a member of the Stade Français tennis club but little more. He won the final of the event, played on sand courts on L’Île de Puteaux, an island in the Seine.

The official report of the first French Championships cattily says that Briggs’ style of play was “ungraceful and risky” and that he had first picked up a racket only two months earlier. This does not say much for the French competitors. They didn’t let the laurels out of their grasp again for a very long time. French men won the next 36 titles.

In large part that was because they banned players who lived overseas from competing until 1925, when it became properly open, if only for amateurs. Other majors opened up rather faster. Wimbledon, which began in 1877, had its first overseas players in 1884 when three American men entered. One of them, James Dwight, reached the semi-finals the next year.

William Glyn, from Durham, reached the final of the first US Championship in 1881, but he was living in Staten Island, whilst Mabel Cahill, winner of the fifth and sixth women’s titles, was a Dubliner living in New York City, but, when Laurence Doherty won in 1903, he was a proper foreigner. Two years later, Randolph Lycett, a teenager from Birmingham, reached the semi-finals in the singles and won the doubles at the first Australasian Championships. Its first overseas singles champion was the American Fred Alexander in 1908.

Like Asterix’s village and the Romans, the French Championships continued to hold out against the invaders. Perhaps it was because the World Hard Court Championships were also held in Paris from 1912 to 1923, save one year when they were in Brussels, and were a fully international event.

After the US won all five tennis gold medals at the 1924 Olympics in Paris, France agreed to open up its Championships to all comers, like the other majors. This year, therefore, is the centenary of the creation of tennis’ “grand slam”.

The term wasn’t used for another eight years, when Jack Crawford, an Australian, won his own country’s Open, followed by the French and Wimbledon titles, leading American journalists to suggest that if he completed the full set in New York it would be like winning all the tricks in bridge. He was denied by Fred Perry, who recovered from two sets to one down in the US final, winning the last two sets 6-0, 6-1.

The first grand slam fell to the American Don Budge five years later and has been achieved only four more times by Maureen Connolly, Rod Laver, Margaret Court and Steffi Graf.

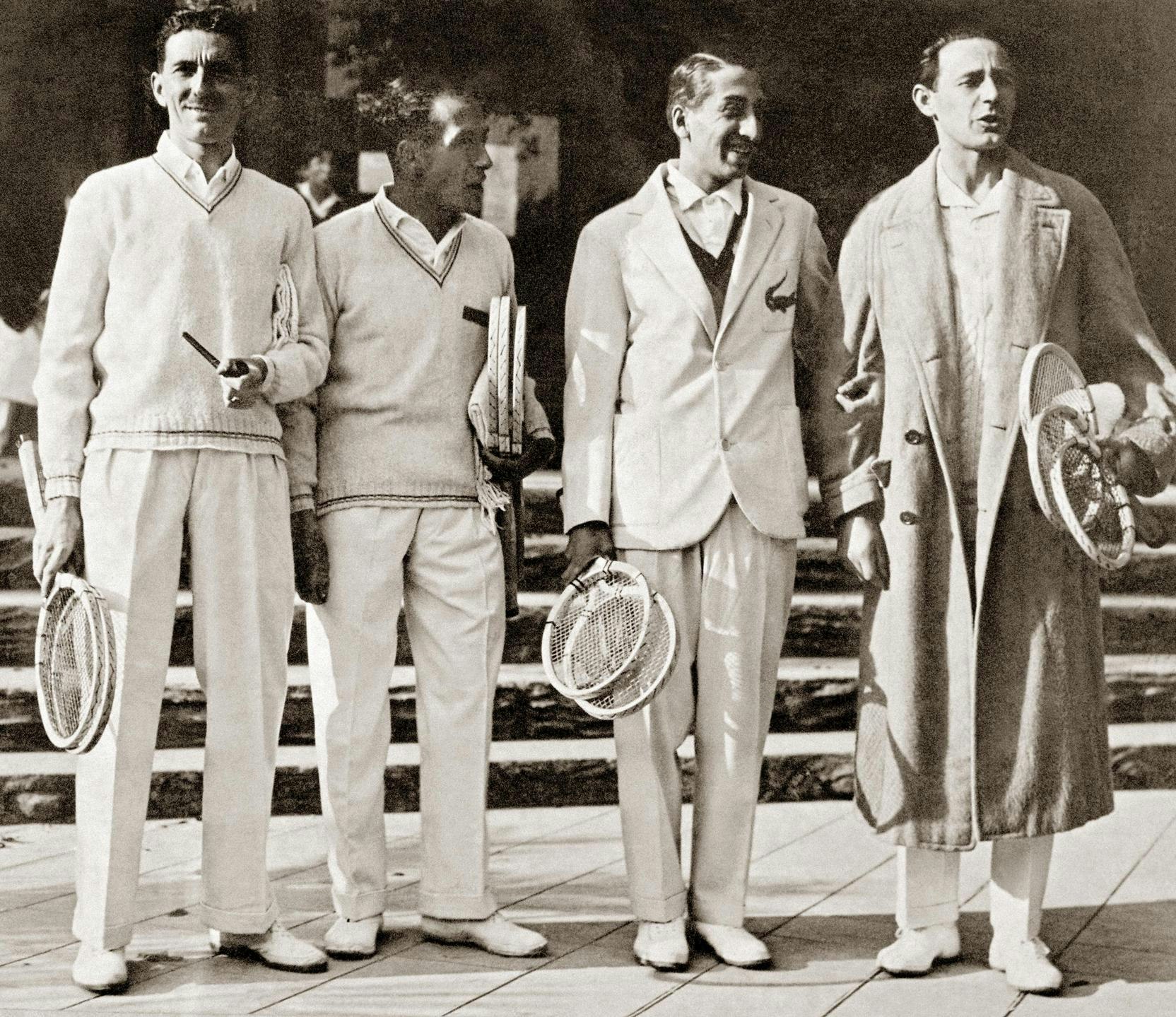

When the French went open, however, the kings of clay were still the Four Musketeers. Jean Borotra, “the bounding Basque”, Jacques “Toto” Brugnon, René “the Crocodile” Lacoste and Henri Cochet won ten French Open singles titles, eight men’s doubles and six mixed doubles. That inaugural Open in 1925 had men from 14 countries, but the final was won by Lacoste in straight sets over Borotra.

Those two teamed up in the doubles, beating their fellow musketeers in five sets in the final. Brugnon then won the mixed doubles with Suzanne Lenglen, who also won the women’s singles and doubles for a French “nettoyage complet”, as they might call a clean sweep.

A pair of American men spoilt a second nettoyage in 1926 but the musketeers continued to win the singles every year until 1933 when Crawford ended a home streak of 36 straight titles since Briggs’ anomaly. Their unbeaten run in the women’s singles had ended at 25 with Lenglen’s sixth title in 1926.

All empires come to an end. British men won the first 30 Wimbledons, American men won the first 22 US Opens. All nations have known long winless periods, too. There were 77 years between Perry’s last Wimbledon title and Andy Murray’s first; there has not been an American male winner in New York since 2003; the last Australian man to win his Open was in 1976.

But the French drought in Paris has felt very long. Since 1932 there have been two home male champions: Marcel Bernard in 1946 and Yannick Noah in 1983. And only three “French” women have won it since the war, none of them actually born in France.

Noah was the third recipient of La Coupe des Mousquetaires, created in memory of those glory boys and presented at Roland Garros, the complex that was opened in 1928 to honour the quartet’s victory in the previous year’s Davis Cup. The trophy and the venue remind us of when Paris finally opened its doors to the world a century ago and beat it. The country is long overdue some new heroes.