The inflation which followed the Covid lockdowns is widely attributed to the disruption of supply caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This drove up oil and gas prices as Western countries scrambled to reduce their dependence on Russian supply, bringing in increasingly tight sanctions. The wheat market too felt the influence as fears grew of disruptions to the important Ukraine harvests.

I challenged this explanation in my IEA study of five Central Banks.1 It showed that whilst inflation did take off in the USA, the UK and the EU, it stayed under good control in Japan and China. As these are both large energy importers it creates some doubt in the idea that energy prices were the main driver. I could have added Switzerland as another country that imports a lot but did not experience high inflation. It is also the case the inflation hit 6.2% in the UK – three times target – before the invasion. In the Euro area it reached 5.9% before Putin moved his army. This again implies there were other causes for the inflation.

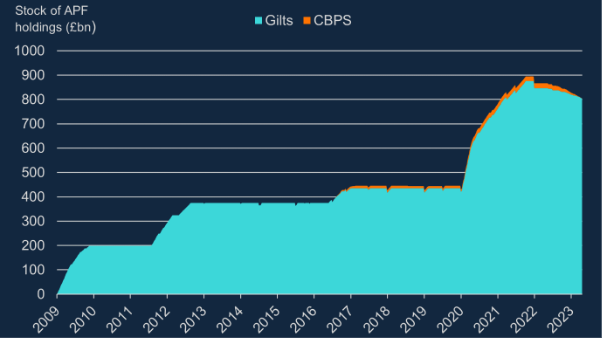

I drew attention to the different monetary policies pursued by the leading Central Banks. The US, UK and ECB embarked on major Quantitative Easing programmes. Japan did not accelerate or change its QE volumes, which had been a regular part of its monetary policy. China and Switzerland did not undertake QE. The big swelling of balance sheets by the Central Banks allowed substantial purchases of bonds, to drive their prices higher and their yields lower. The Fed more than doubled its balance sheet from $4.18tn in January 2020 to $8.94tn by April 2022.

The Central Banks concerned deny this caused the inflation. This is curious. The idea of buying up government bonds was to create an inflation in the price of bonds. They defended their actions as a necessary course once base interest rates were close to zero. It was designed to lower longer term rates, which are determined by the price of bonds rising to lower the interest charge. It was also bound to be the case that the inflation in bond prices spread to other assets. Given the scale of the aggressive buying, sellers of the bonds were likely to go to buy shares or property or other riskier assets which were offering a better income than the expensive bonds. This in turn created upwards pressure on these asset prices. It was only a matter of time before some of the bond buying created extra demand for goods and services, as individuals and institutions decided to spend some of the windfall profits they were making on selling their bonds. This was more likely to be inflationary given the big interruptions to supply created by Covid lockdowns and the slow and partial recovery in supply as lockdowns were relaxed.

Quantitative Easing had been a partial remedy to the situation after the banking crash. There the collapse of credit was creating a shortfall in demand, so monetary easing could supply some extra demand to facilitate recovery. After Covid, where some of the problem was shortage of supply, simply pumping up demand with more money could be inflationary.

The late reaction to the inflation

The leading Central Banks forecast inflation would stay low despite their policies. It rose. They then said it would be a temporary phenomenon caused by dear energy, so they would look through it. It rose further. They then decided they needed to undertake a traditional response to inflation. They embarked on a rapid series of interest rate rises. The US, UK and ECB decided to accompany this by designing Quantitative Tightening polices. These were designed to bring their balance sheets back down by reducing the amount of bond they owned. They had financed the bond purchase by creating commercial bank reserves or deposits with the Central Banks, so QT entailed reducing these reserves as the bonds were repaid by the issuing state or as they were sold to the private sector. The three offending Central Banks chose different routes to undertake QT from the range of options before them.

The Central Banks’ options to implement Quantitative Tightening

The easiest and gentlest form of QE, which all three adopted, is to allow the portfolio to run off as bonds are repaid. Each Central Bank had bought a range of bonds of different maturities. When the state repaid the debt they had under QT the Banks had been reinvesting the money in another bond. The UK decided to make no further reinvestments whilst the US and ECB decided on a total for QT reduction in bonds. If a lot of bonds matured around the same time they would reinvest the excess over their target.

The tougher form of QT is to add to the repayments some direct sales of bonds in the market. The Bank of England decided on this approach. This decision had further consequences, increasing the losses on the transactions, forcing the Treasury to make payments to offset the losses, and arguably over-tightening by reducing commercial bank reserves more rapidly.

Central Bank losses

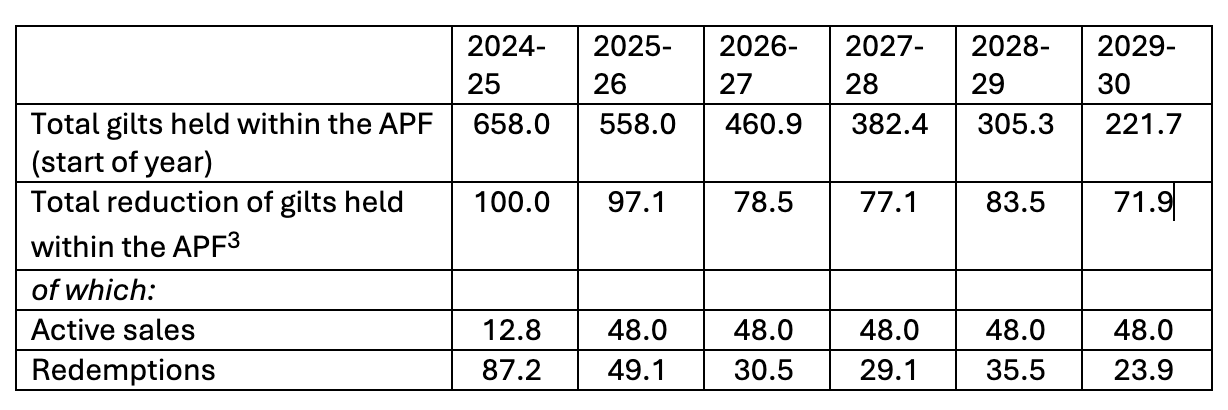

The OBR’s autumn 2024 forecast of losses looks as follows:

Table 1: APF annual runoff assumptions (in £ billion), forecast (October-September year basis)2

The OBR go on to explain:

The OBR go on to explain:

Contributions from the APF to PSND have risen by an average of £1.9 billion a year compared to our March forecast due to a higher forecast for Bank Rate and gilt yields, and now add a cumulative £78.1 billion to PSND across the forecast period. The higher expectations for Bank Rate and gilt yields, combined with the latest runoff path, imply a cumulative net lifetime loss of £115.7 billion, which is £11.5 billion higher than we estimated in our March 2024 Economic and fiscal outlook.8 This is not a comprehensive assessment of the overall fiscal impact of the Quantitative Easing (QE) programme, which supported the economy, asset prices, and financial markets at various points of stress over the past 15 years. These wider economic and fiscal benefits would need to be considered in any comprehensive assessment of the impact of QE.4

Quantitative Easing to be followed by Quantitative Tightening was designed to make the Central Banks the world’s worst bond dealers, more or less guaranteeing a loss on their transactions. Where the Central Bank paid more than the repayment price for the bond, as they often did, there was a guaranteed loss if they held it to redemption. The OBR is now forecasting total losses from end 2022 of £240bn, a lifetime loss of £116bn on top of losing the £124bn of already booked profits. As they switched to increasing their short-term variable rate borrowing, their commercial bank reserves, when short rates were around zero there were also likely to be substantial losses when base rates went up. The European Central Bank decided it would take action to limit these losses. It told commercial banks part of the money they deposited with it was a requirement of money policy and would receive no interest rate reward. The rest would receive a lower deposit rate than the Bank’s base rate and their higher lending rates, like a commercial bank. The Fed and the Bank of England decided to carry on paying the full base rate on reserves. The Bank of England had changed its policy in 2006 away from paying no interest on bank reserves.

The three Central Banks were in different position over the losses. The Bank of England does not worry about them, as they are reimbursed pound for pound by the Treasury. They acted as Agent of the Treasury in making the acquisition, as they had sought approval of the government and had required a full indemnity for the actions. The Federal Reserve Board as custodian of the world’s main reserve currency pointed out that it cannot go bust however big the losses might be, as a Central Bank can always create money to pay the bills. It decided to create a matching asset for the losses called future profits and place them on the balance sheet. In due course it will resume making profits and will gradually reduce the accumulated losses. The European Central Bank is a federated structure, owned by the Central Banks of the member states which it otherwise directs and controls. It therefore decided that the bulk of the losses would be the responsibility of the member states’ central banks. If they felt their accumulated losses were a problem, they could ask their governments to recapitalise them, as the UK does for the Bank of England. They are also keeping the losses under better control by not selling bonds in the market and by reducing the interest cost of owning them.

Deputy Governor of the Bank’s chart for the shift from QE to QT

When the Bank decided it had cut rates as much as it could but still wanted more stimulus, they proposed Quantitative Easing to the Chancellor. Every pound of bond buying since has been done with the express prior permission of the Treasury and with a full guarantee. This means the Bank’s only independent power is still the right to fix base rate.

Some politicians defending the Bank’s independence think that it transfers responsibility for inflation from government to the Bank as the prime target of Bank rate policy is to keep inflation to 2%. This decade has shown that the Bank can make big mistakes with inflation. The public blames the government. Labour in office over the banking crash did intervene to get an emergency cut in rates when the Bank and other leading central banks were keeping the rates too high. They were right to do so, though it was too late to stop the Great Recession.

The Bank of England invades fiscal policy

Life is not as simple as many would have it. They think an independent Central Bank uses interest rates to keep inflation low. An activist government decides spending, tax and borrowing. Most accept the need for some fiscal rules, as they see there are limits to how much a state can borrow. The two keep to their own tasks. The Bank could warn if there is too much borrowing, with rate rises to deter it. The government could borrow more to offset the impact of high interest rates on growth up to the limits of tolerance of markets. It is best if they do talk to each other to get some balance, yet the doctrine of independence can limit these exchanges.

Now that the Bank is running QE programmes followed by QT programmes, it is invading budgets and fiscal policy. In the QE period the Bank sent the Treasury £124bn of accumulated profits on borrowing cheaply and enjoying bond income. It also facilitated a huge increase in state debt at very low rates. Now government faces the refinancing costs of this debt, as rates have gone up a lot.

Worse still, the Treasury has to reimburse Bank losses. The OBR forecast at autumn budget 2024 predicts £240 bn of losses from the full wind-down of the bond portfolio. This is a mixture of losses on bond sales in the market, losses on repayment of bonds bought above their payback value, and the running losses on the interest charges. This means the state has to find, say, £20-40 bn a year to pay the Bank, which comes from taxpayers or additional borrowing. As a result of the debt surge and high inflation post Covid, the government also needs to find much larger sums to service its debts.

These twin pressures leave the government short of money to pursue its priorities.

The fiscal rules

The UK’s fiscal rules have stopped Chancellors spending more or taxing less to the extent they want. They have failed to rein in deficits or help boost growth. They are changed a lot, but all share the same big weakness. They are based on targets for 5 or 3 years hence. They are judged based on OBR forecasts that are understandably wrong. The OBR may be too pessimistic limiting Chancellor scope to boost the economy. The government will often want to use optimistic assumptions about what will be happening in five years’ time. They can feed in unrealistic spending plans for later years. This has been made worse by the big upwards move in interest costs and costs of the Bank.

The Truss bad month

The Truss budget was out to boost growth by tax cuts. Unfortunately she also added a very expensive though temporary subsidy for energy users, which gave help to all, not just those on low incomes. Markets thought the borrowing too high.

The prices of government bonds fell, pushing up interest rates on the debt. This was widely blamed on the budget though most of the rise had nothing to do with it. Bonds fell in the days before the event as the Bank on the eve of the budget put up base rates, signalled more rate rises to come and announced a big sales programme of bonds. The Bank wanted a big fall in bond prices bringing dearer money. On the Monday after the budget it emerged that many pension funds owned bonds they could not afford through levered funds called LDI. They had to sell some to pay calls on their exposed positions, this hit the market badly.

Shortly after the Bank of England reversed from threatening bond sales to buying, so the market recovered. The Bank’s own pension fund had a large LDI position so they understood the problems they had created.

Longer interest rates rose above the Truss levels the following year. They went even higher after the Rachel Reeves budget. No growth is especially bad for public finances. It usually leads to more borrowing to make up for lower tax revenues.

Bank of England losses disrupt budget finances

If the Bank of England lost less, or if it simply reported losses without Treasury compensation, the Chancellor would have more money to spend. Given free choice, a Chancellor is unlikely to think sending the Bank more capital to pay for bond losses is a key priority. It is curious no recent Chancellor has challenged this invasion of fiscal policy. It has been calculated simply stopping the Bank selling bonds in the market instead of waiting for repayment is costing taxpayers £13.5 bn a year. We need to probe the Bank’s rationale for this conduct, bearing in mind the ECB and Fed are not doing this.

The Bank says there is no monetary purpose to QT

This is an odd view. They say QE and QT are not symmetric. Whilst QE was designed to push up bond prices and lower rates, QT is apparently not going to push down bond prices and raise rates. They say they pace the sales and signal well so the market can absorb them. They then acknowledge there could be a small upwards effect on interest rates.

It is difficult to believe this. Selling more on such a big scale must have some negative impact.

The fact that the Bank says there is no monetary effect or does not want one means there is no reason for the government to hold back over asking to slow the sales. The Bank has its independence in Monetary Policy, not fiscal policy.

How do they judge how much to sell?

The Bank freely admits there is no clear basis for deciding how much bond to sell. They rightly see it as how many reserves to keep in the system for the commercial banks. They say they do not know how many reserves are needed.

They also believe there is currently a large surplus so big that sales are appropriate. However, they demonstrate their uncertainty by also creating a repo facility to allow banks to add reserves if there is a shortage. This again argues that slowing the pace of balance sheet reduction is not harmful.

The Bank argues it needs a smaller balance sheet in case of another crisis

This is in one sense a council of despair. They need to slim in case they help create another monetary crisis. As the Bank can expand its balance sheet any time it likes whatever the starting level this is not compelling. We have just seen that these Central Banks are not normal banks or businesses so they can get away with balance sheet expansion in certain conditions and can look to their state sponsor to recapitalise if that matters.

The dangers of QT

This aimless policy must be seen as a monetary tightening by the Monetary Policy Committee. Their blithe assumption that is has little or no monetary effect, coupled with their belief that their only monetary tightening tool is to raise interest rates, is misleading. Other Central Banks see the relationship between reigning in QE and rate moves, with the Fed reducing the pace of QT as part of its modest early relaxation alongside a rate cut. Every sale of a bond to the private or banking sector removes funds from them that could be spent or used for more lending, so it subtracts from potential activity. QT has naturally coincided with low rates of monetary growth, just as QE led to rapid rates of money growth.

QT can represent a triple tightening. There is the withdrawal of cash as the bonds are sold. There is the lower price of bonds meaning higher interest rates as a result of sales. There is the impact on state finances of sending the bill for the losses to the Treasury, reducing scope for fiscal stimulus.

Recommendations to the Bank of England to review their practices

The Bank’s MPC needs to take money growth more seriously. The MPC should have to report on the rate of money growth and on the velocity of circulation of money as part of its analysis of inflation. They need to be included in the model for future inflation forecasts.

The MPC needs greater diversity of thought around the table, including at least one or two members who think money matters and who think broad money growth has an influence on future inflation.

The MPC needs to review its Quantitative Tightening policy, asking why it is out of line with the ECB and Fed, and see what it can learn from their practices.

It needs to examine the extent of the impact of QT on growth and activity, interest rates and liquidity in the banking system.

Policy recommendations for government and Bank

As the policy to buy and hold bonds has always been a joint policy where the Treasury can say no, and as there is a full Treasury guarantee for the losses, there needs to be an urgent meeting of Treasury and Bank with a view to ending the sales of bonds in the market which generate large losses. This is an unnecessary intrusion into fiscal policy.

The two also need to review other ways of reducing losses including differential deposit and loan rates for the Bank of England to cut interest costs on reserves. The two should agree a lower profile of losses to the ending of the bond portfolio.