Clinging to the fringe of a sweeping plateau at the southernmost tip of Syria, a cluster of six quiet farming communities has emerged as an unlikely, but hotly contested, geopolitical fault line.

Above the Yarmouk Valley in Daraa province, 25,000 villagers find themselves squeezed between two regional superpowers.

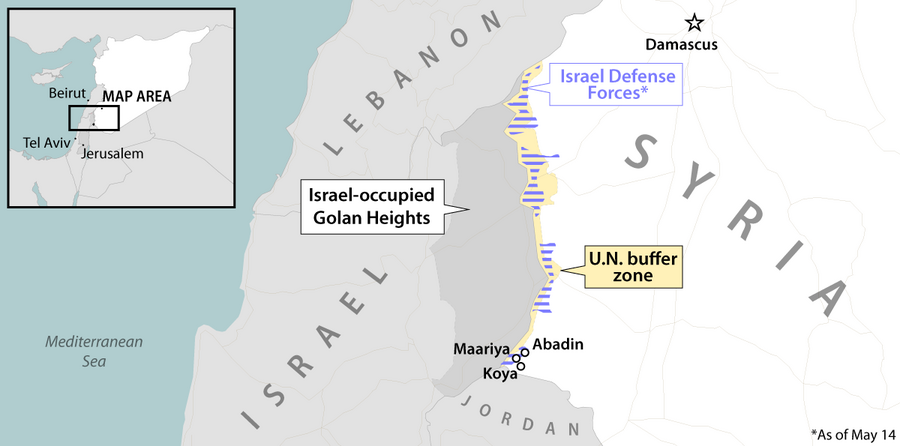

On one side is Israel, whose troops have seized a United Nations-designated demilitarized zone and pushed into a sliver of Syrian territory that includes the villagers’ homes and farms. Its aim is to push forces loyal to Syria’s new Islamist-leaning government far from the borders of the strategic Golan Heights, which Israel occupied in 1967.

Why We Wrote This

With Israel now occupying slivers of additional territory in southeast Syria, simple farming villages find themselves cut off from the rest of their country and struggling to live on a geopolitical fault line between Turkey and Israel.

On the other side is Turkey, which in recent years has adopted an increasingly adversarial stance toward Israel, and which this week signed a security alliance with Syria and Jordan. The prospect of Turkish soldiers operating from Syrian military bases south of Damascus is adding to Israel’s alarm.

Because Israel has stationed troops here, the Syrian army, police, and government-aligned militia cannot enter, leaving villagers cut off from the rest of the country and fending for themselves.

Israeli reconnaissance drones hover overhead. Israeli soldiers regularly stage nighttime raids on people’s homes.

But the people here say they simply want to farm.

“We did not attack you. Why are you coming to us?” Farouq Ahmed, a community leader in the village of Abadin, recalls telling an Israeli officer. “We don’t have weapons, we don’t have Islamists. What have we done to you? We just want to live.”

Israel’s move into Syria

When former President Bashar al-Assad fled Damascus last December, Israeli forces crossed the U.N. buffer zone and moved east, deeper into Syrian territory. In March, they began to advance further, encroaching here on this triangle of Syrian land between Jordan and the Golan Heights.

In late March, the advance sparked armed resistance from local residents who, relatives say, were defending their lands – leading to Israeli airstrikes that killed nine people.

Syria’s interim president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, is seeking to ease tensions with Israel and give assurances to the West. He has opened diplomatic back channels with Israel and, in a meeting Wednesday with President Donald Trump, expressed Syria’s eventual willingness to join the Abraham Accords.

Yet the Israeli occupation here persists. Tensions remain high.

“People are being impacted economically, socially, psychologically. Entire communities are being besieged, pressured, and cut off from their livelihoods,” says Tarek Khalil, a Daraa lawyer who has been documenting Israel’s territorial violations. Pointing to a new hilltop position that Israeli forces have established at the edge of Abadin, he says, “If Israel keeps entering and storming villages, this will add fuel to the fire.”

Yarmouk Valley’s farmland

At the center of tensions are hundreds of acres of land in the Yarmouk Valley that these farming communities rely on, but which are now off-limits, the other side of the Israeli lines. The valley is rich with fields of wheat and barley, zucchini, tomatoes, and peas; groves of lemons, olives, and pomegranates; and thousands of beehives.

Farmers can no longer irrigate their crops, and shepherds can no longer reach their pastures. They are obliged to keep their flocks penned up, spending hundreds of dollars each month on animal feed. Shepherds are selling herds at a third of their market price.

“The Yarmouk Valley is our only source of living. We are willing to risk our lives for this valley,” says Hani Mohammed, a farmer in the village of Koya, whose daughter was wounded by shrapnel in an Israeli drone strike last month. “If we lose this valley, we will die of hunger.”

In tough times, residents would normally sell off a few acres of their land, but now they can’t find any takers, even at a discount.

“When you say the village’s name, people say, ‘No, I won’t buy here. Maybe tomorrow Israel will come and take all of it,’” says Mr. Ahmed.

“We did not attack anyone”

Villagers say they want to go back to the terms of the 1974 U.N. Disengagement Agreement, which demarcated lines for Israeli and Syrian forces that were observed until earlier this year.

They are seeking support from the United Nations, Turkey, Gulf countries, Jordan, and anyone else who could help secure an Israeli withdrawal from their land.

“We did not attack anyone and we do not call for an attack on anyone,” says Yassin Damara, a community leader in the border village of Maariya. “We want to live in cooperation … and affection with all our neighbors, even Israel.

“But,” he cautions, “not at the expense of people’s rights and lands.”

Residents say the armed groups who used to operate in the region left shortly before Mr. Assad’s fall and have not returned. The only arms they have, they insist, are hunting rifles used to protect their crops from wild boar.

The men killed fighting Israeli forces, “did not go to Israeli land to fight Israelis on their lands. Israel came to their towns and they rose up to defend their lands and country,” says Mr. Damara.

Israeli forces reportedly continue to raid homes suspected of storing weapons, and have dropped leaflets warning residents about “gunmen.”

Abadin resident Islam Hussein’s husband, Khalil Aref, a fowler and hunter, was arrested by Israeli authorities last month, leaving her to fend for their three young daughters without the household’s breadwinner.

“We always considered that we are in our valley and they are in their valley,” she says of Israelis. “We never interacted.

“Now I want to know what charges my husband faces and for him to be freed, to return to his family.”

A willingness to fight

Some residents strike a more defiant tone.

“We want this to be resolved peacefully and ask international organizations to constrain Israel,” says Mr. Mohammed, the farmer in Koya. “But if these incursions are repeated, we are willing to go into action and fight. We are just awaiting Sharaa’s word.”

“They have pushed us to the point of Palestinians: where dying defending your land is better than living and losing everything.”

That call to action is likely not to come.

Damascus has gone at length to ease Israel’s concerns, with Mr. Sharaa acknowledging Syria and Israel have established indirect talks to “calm” the situation so that “it does not reach a level that both sides lose control.”

The Syrian military and government-aligned forces refuse to enter this contested zone to avoid any conflict with Israel.

But observers worry that, amid economic hardships and wilting farms, the vacuum left by the state may be filled with the extremist groups that Israel is trying to prevent from emerging.

“There are no extremist groups here, but with poverty, desperation, and hardship, the concern is that Israeli military violations may push people to extremism,” says Mr. Khalil, the human rights lawyer. “That will be a lasting negative impact of this occupation.”