This article is taken from the May 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

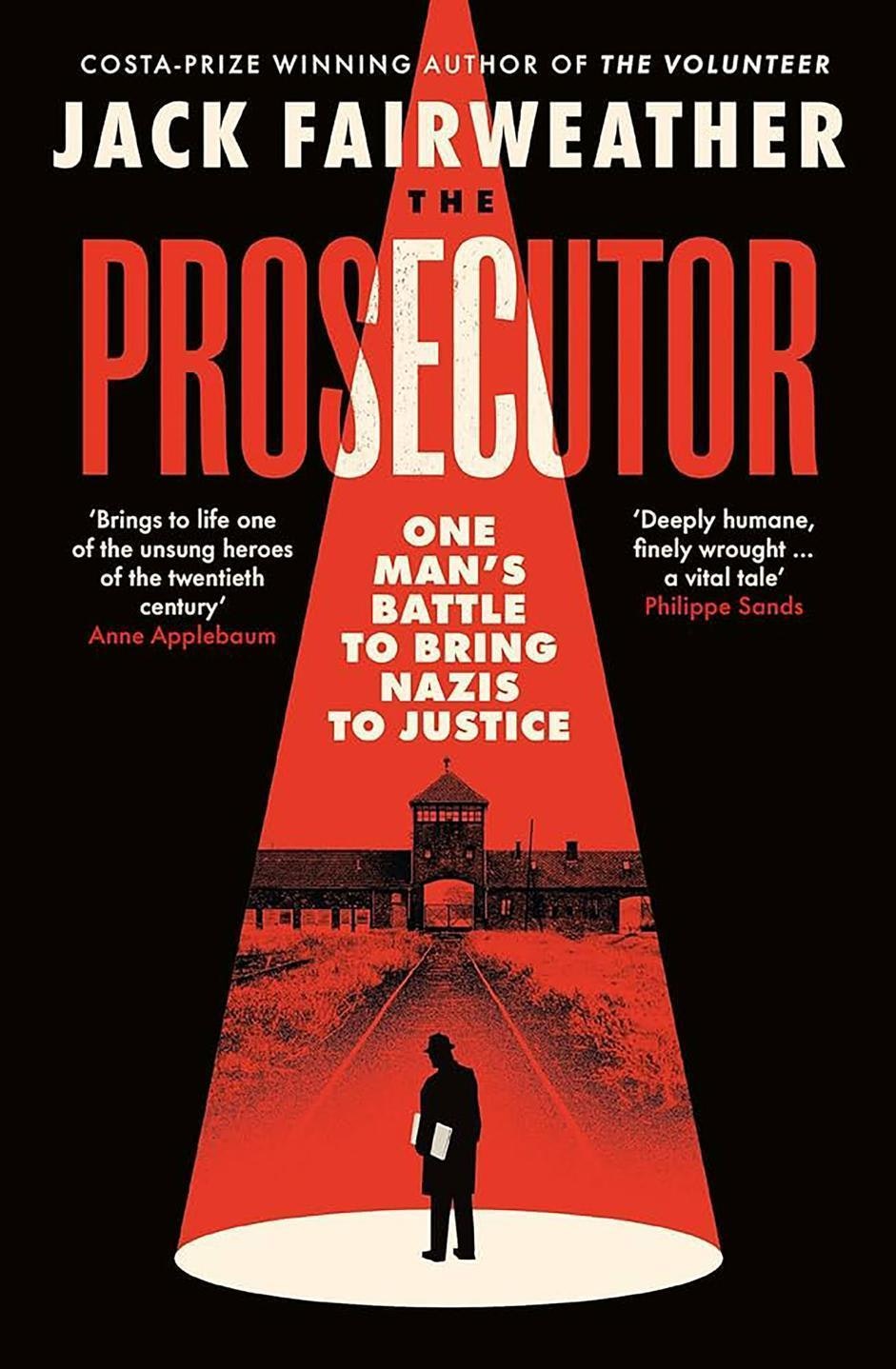

Despite the number of holocaust-related titles that now appear in the book trade, there is usually (in my experience as a publisher of history titles) one specific book that becomes a beacon, or flagship for the genre. The Prosecutor could very well be seen as that in the years to come. I tip my hat to historian and award-winning writer Jack Fairweather for focusing on the life of the gay, socialist, Jewish lawyer Fritz Bauer, a toxic combination for living in Nazi Germany. Bauer’s life is a remarkable story.

We are fully conversant with the appalling genocidal crimes of the Nazis before and during the Second World War: the systematic persecution and subsequent destruction of the Jewish population throughout Europe, which would result in the deaths of millions in extermination camps that processed murder on an industrial scale. This is viewed through the prism of Bauer’s survival, escaping Nazi Germany to become a refugee in Scandinavia, then returning to his native country to become a campaigning post-war prosecutor.

He would galvanise government support at local and national levels to lift the lid on the thousands of ex-Nazi administrators and military personnel seeking anonymity. In so doing, Bauer and his loyal band of legal experts sought to hold their countrymen to account for their part in the Final Solution — whether they were active participants or simple bystanders witnessing the horror in silence.

The Prosecutor initially takes the reader on a page-turning adventure. The bulk of the narrative sets out to tell Bauer’s long journey to investigate, then prosecute a number of figures within the Nazi apparatus and publicise their trials to maximum effect, despite the inevitable backlash. The Nuremberg Trials immediately after the end of the war in Europe had supposedly put to bed the culpability of who was directly responsible for Nazi Germany’s role in the Second World War. Bauer’s work now challenged this assumption.

As the Cold War developed throughout the 1950s, two Germanys evolved to serve either side — the allied-sponsored FDR (Federal Republic of Germany) in the West and the Soviet backed GDR (German Democratic Republic) in the East.

Within this balancing act, the crimes of the Nazi era could have been conveniently brushed under the carpet to serve a greater strategic purpose, with the value of Nazi-era spies overriding their previous criminal activity. Bauer methodically trod a treacherous political path and in doing so challenged the accepted government policy of letting “bygones be bygones”.

The Holocaust did not happen in an uncoordinated fashion outside Germany’s borders. Bauer peeled away the official narrative to reveal to West Germans that it was, instead, a detailed policy, supported throughout all layers of the Nazi administration and endorsed by the general population. His countrymen now looked into a mirror of Bauer’s making.

Fairweather was given full access to Bauer’s personal papers and permission to interview his surviving associates and family. He paints a vivid picture of a man in a hurry to bear witness to mass murder, who by publicising it hoped to prevent any repetition. I was pleasantly surprised to read accounts of post-war events I thought I had a handle on.

One such is the trial of Adolf Eichmann, an officer in Hitler’s paramilitary arm, the Schutzstaffel, who performed a key role in the Wannsee Conference in early 1942. In a single meeting, Nazi administrators mapped out the structure of the Final Solution to the “Jewish Question”: industrialised murder.

Bauer would play a significant role in locating Eichmann in South America and lobbying the Israeli secret service to bring him to justice. By the time of Eichmann’s execution in 1962, more than half of West Germans viewed it as justified. Bauer would continue to push for a national debate on the genocide. It was one thing to see the Holocaust as an evil act but quite another for a whole country to see itself as enabling it.

His ambition to bring the debate to a national and global stage would be achieved in the final years of his life in the late 1960s, as he sought justice for those who had perished in one of history’s greatest centres for mass murder — Auschwitz. In bringing his life and work back to public attention, Jack Fairweather has achieved something quite remarkable.