Living next to a golf course could increase your risk of developing incurable Parkinson’s disease by a staggering 126 per cent, a study has suggested.

American experts found people living within one mile (1.6km) of a course were far likelier to be diagnosed with the condition than those living at least six miles (9.7km) away.

The team suggested the higher rates of Parkinson’s were linked to increased exposure to the pesticides used to keep the pitch aesthetically pleasing to golfers.

They suspected people living in these areas were being exposed to these chemicals via contaminated water supplies and potentially through the air.

A separate analysis by the authors found people whose household water came from an area with a golf course had double the chance of Parkinson’s compared to those who didn’t.

Using health data from 6,000 people they found the risk was highest in those living one to three miles (1.6km-4.8km) from the course.

However, independent scientists not involved in the study have urged caution over interpreting the results.

In the study, researchers looked at the addresses of 419 Parkinson’s patients from Minnesota and Wisconsin.

American experts found people living within one mile (1.6km) of a course were far likelier to be diagnosed with the condition than those living at least six miles (9.7km) away. Stock image

They then matched these people on sex and age to 5,113 healthy people.

Analyses revealed Parkinson’s patients were far more likely to be living near a golf course or have their water come from an area containing one.

Writing in journal JAMA Network Open, the authors said multiple pesticides known to be used on golf courses had been linked to disease.

‘For years pesticides including organophosphates, chlorpyrifos, methylchlorophenoxypropionic acid, 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid, maneb, and organochlorines known to be associated with the development of Parkinson’s disease, have been used to treat golf courses,’ they wrote.

Charities, like Parkinson’s UK, also state that current evidence suggests exposure to pesticides increase the risk of the disease in some people.

The authors of the new study—while acknowledging their research had limitations—said it suggested reducing pesticide use on golf courses could protect people from Parkinson’s.

‘Public health policies to reduce the risk of groundwater contamination and airborne exposure from pesticides on golf courses may help reduce risk of PD in nearby neighbourhoods,’ they said.

However, British experts have urged caution.

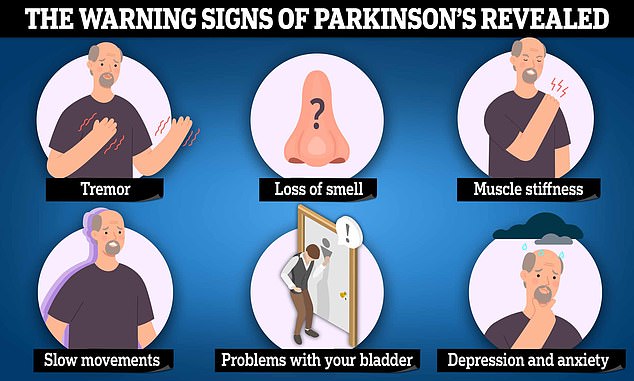

Symptoms of Parkinson’s include uncontrollable tremors, slow movements and muscle stiffness

Professor David Dexter, director of research at Parkinson’s UK, said a critical limitation is that the study didn’t solely look at people who had lived at golf courses for long periods.

‘Parkinson’s starts in the brain 10-15 years before diagnosis and the study didn’t only use subjects who permanently lived in the area,’ he said.

‘This would not only affect participants’ exposure, but also suggests their Parkinson’s could have started before they moved around a golf course.’

He added that while the study had linked the disease to pesticide contaminated water, the scientists hadn’t directly tested the water supplies to prove they were present.

‘This lessens the validity of the claim of pesticide exposure because the studies have not been carefully controlled,’ he said.

Dr Katherine Fletcher, research lead at the charity, also said other factors might have contributed to the Parkinson’s cases.

‘This study supports the association between pesticides and Parkinson’s,’ she said.

‘However, it’s quite reductive and doesn’t take into account how someone might have been exposed to pesticides at their workplace or whether they have a genetic link to the condition.’

Actor Michael J Fox (pictured here) was diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease at just 29 years old. He now advocates for more research into the condition

She added the results are also unlikely to be directly relevant to people in Britain.

‘In Europe and the UK, the use of pesticides are strictly controlled, and some, like paraquat, are banned, due to concerns about their wider health and environmental impacts,’ she said.

‘So, the risk of exposure to these for most people is extremely low.’

The latest research follows another study this week that linked regularly eating ultra-processed foods to nearly tripling the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease.

About 90,000 Americans and 18,000 British people are diagnosed with Parkinson’s every year.

It is caused by the death of nerve cells in the brain that produce dopamine, which controls movement.

Experts are still working to uncover what triggers the death of these nerves.

However, current thinking is that it’s due to a combination of genetic changes and environmental factors.

It leads to people suffering from tremors and stiff and inflexible movements that can eventually rob them of their independence.

Patients can also, as a consequence of their disease, suffer from other problems like depression and anxiety.

Parkinson’s has no cure and is progressive so will inevitably get worse with time.

However, treatments are available to manage symptoms and maintain quality of life for as long as possible.

Risks of developing the condition broadly increases with age, with most patients are diagnosed over 50.

Patients can also respond differently to treatments—some find drugs offer a solution whereas for others they fail to work.