Two bullet holes from the bad old days still scar the black metal doorway of Ishmail Schbaita’s busy corner shop in Copenhagen.

The migrant gangster who haphazardly fired the shots from a 9mm pistol during a drugs turf war has long disappeared from this once-dangerous suburb of Norrebro in the Danish capital.

He was deported as Denmark cracked down on rising crime caused, to a large degree, by the uncontrolled wave of 1.3 million migrants, which swept into Europe ten years ago, changing the face of the Continent for ever.

Denmark was not immune to the consequences of thousands of foreigners settling on their patch. But its Left-leaning government, which came to power in 2019, promised to curb migration to ‘protect Danishness’ – and acted on the pledge…

The country famously banned the burka, the garment fully covering the face and body worn by devout Islamic women who’d been brought to the country by their husbands. New rules came in compelling all newcomers and their children to learn Danish or lose asylum-seeker benefits.

A stone’s throw from Mr Schbaita’s shop, residents of a notorious housing estate, Mjolnerparken – which had been categorised officially by Denmark as a ‘ghetto for non-Westerners’ – were moved around the country to stop a ‘parallel’ foreign society growing up.

‘Now the area is 99 per cent safer,’ Palestinian-born Mr Schbaita, 62, told us last week as he sat outside his shop in the evening sun during a rare spring heatwave. ‘There are few bullets or gangs. Many who lived in the ghetto have been dispersed. The criminals in Mjolnerparken have been deported. Denmark did what it promised us.’

Indeed, the country is considered a model for successful control of immigration.

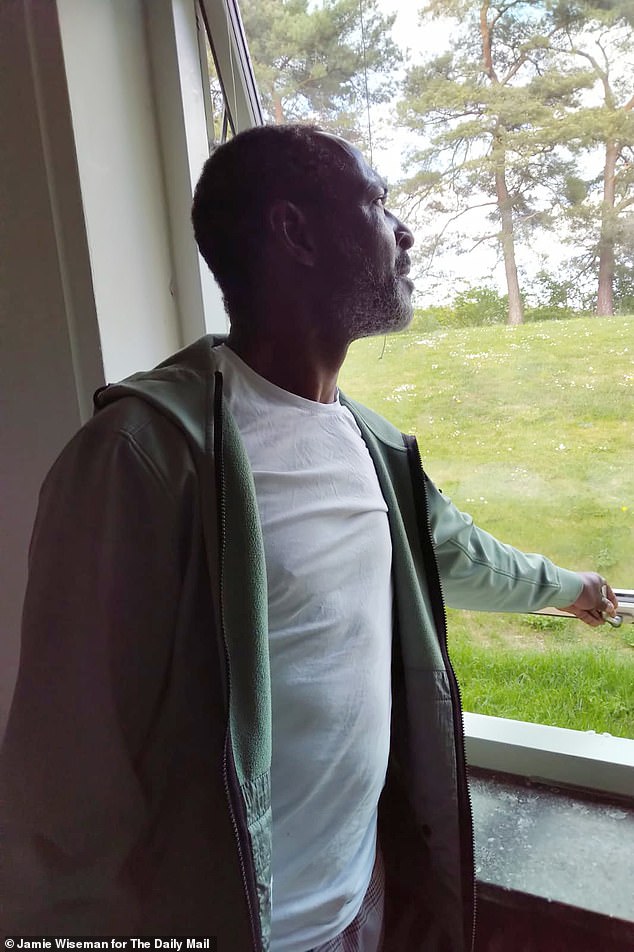

Cameroonian lawyer Ndam Carlson Agwo, 48 ,speaking to Sue Reid at the deportation centre

A 23 year old Kurdish migrant (no name) who arrived in Denmark as an unaccompanied minor, pictured speaking to Sue Reid

Ndam Carlson Agowo spends his days collecting returnable plastic bottles to earn pocket money

It is a stark lesson for Labour. Immigration dominated last Thursday’s local elections when the party, with its dismal record on border control, suffered an astounding defeat at the hands of Nigel Farage’s Reform, which has pledged to deport foreign criminals if it ever wins control in Westminster. And it is clear Denmark’s hardline stance is now firmly on Sir Keir Starmer’s radar.

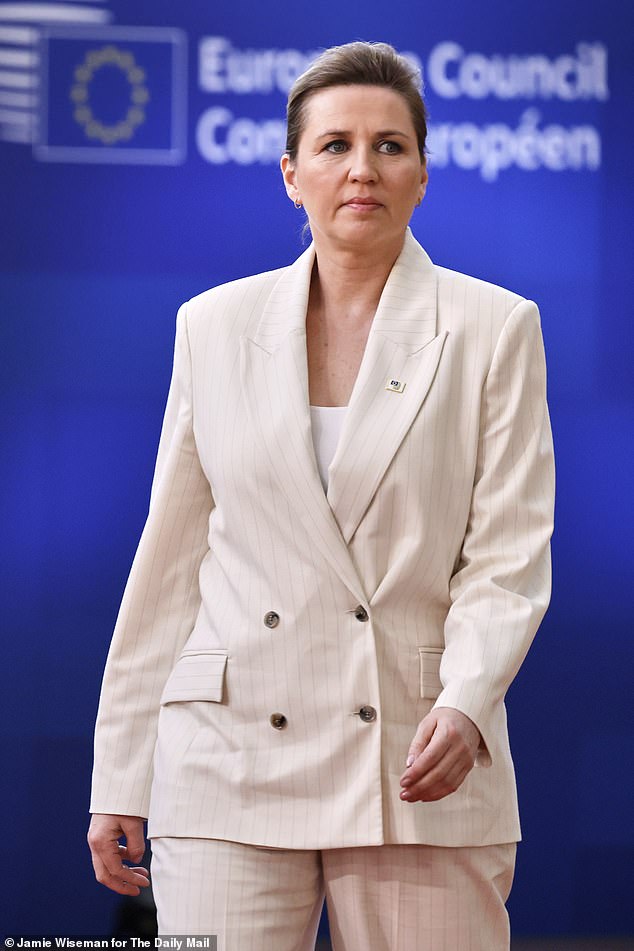

In February, the Prime Minister met his Danish counterpart, Mette Fredericksen, in Downing Street to hear about her approach. Her government had recently insisted that out-of-control immigration had become a ‘threat to the daily life of Europe’ and that she would like to bring numbers down to near zero.

At the heart of the policy is a determination to protect the livelihoods of working-class Danes, to safeguard their jobs and to stop schools and welfare systems from being overwhelmed by newcomers.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating. Government statistics show that in Danish schools, the lower the age of pupils, the more Danes there are in the class.

This is an indication that the proportion of young ethnic minority families here is falling – and it is the reverse of what is happening in much of England’s education system where last year 37 per cent of pupils were from a minority ethnic background.

A side benefit for Ms Fredericksen’s Social Democrats is that her policy has effectively pulled the rug from under the feet of her Right-wing political opponents who have similar views to the Reform Party. The Scandinavian example shows that even a Left-leaning government can get a grip on immigration if it uses common sense.

Danish immigration minister Kaare Dybvad Bek has made it clear: ‘We stand very hard against giving migrants the right to remain here. If you’re rejected as an asylum seeker, you have a very low possibility of staying in Denmark.’

Asylum applications have dropped by almost 90 per cent over the past decade. Last year they plummeted to 2,333, while the UK total hit a record 108,138.

A man who collects bottles from the bins to recycle for cash speaks to the Mail’s Sue Reid

Denmark’s Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen’s government had recently insisted that out-of-control immigration had become a ‘threat to the daily life of Europe’

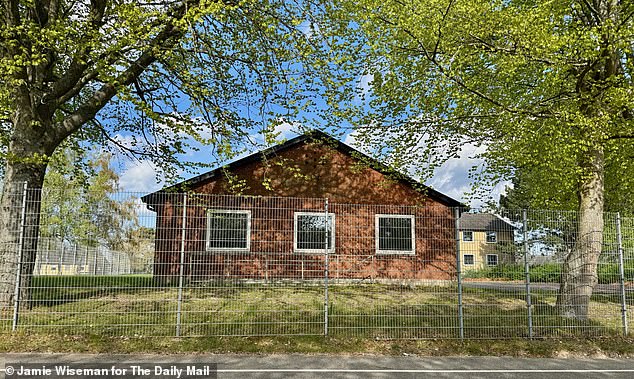

The Sjaelsmark deportation centre, an hour outside of Copenhagen

Ndam says he will face jail and possibly death if he is sent back to Cameroon

Ndam pictured showing Sue some of the bottles he collected for his pocket money

And yet there’s no doubt that Denmark, with a population of just six million, once had a huge problem – asylum requests here reached 21,316 in 2015 as the rush of migrants entered Europe at the invitation of German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

However, it appears to have controlled numbers by quite deliberately introducing a hostile environment for migrants. Asylum-seekers refused the right to stay are denied benefits. They get food, served three times a day, at the country’s two deportation camps, one of which was visited last week by The Mail on Sunday.

They are sent to the camps to await removal by the Danish Returns Agency, which gets extra funds for results.

Controversially, Denmark’s border force has powers to confiscate items such as jewellery and watches from incoming migrants to help fund the cost of their stay. ‘The officials will even remove the gold carried by a widow whose husband gifted it to her in case he died in battle and she needed to escape to Europe,’ one politician on the Danish Left complained to me in Copenhagen.

Migrants who tire of Denmark and return home voluntarily are given a £4,500 sweetener to leave. And if a migrant’s country of origin is deemed ‘safe’, such as Syria after the recent fall of President Bashar al-Assad, even a successful asylum seeker can lose Danish residency and face being returned home.

Crucially, the ‘ghetto law’ has led to government regeneration of inner-city neighbourhoods which had to cope with large migrant influxes after 2015.

Places such as Mjolnerparken have been transformed into hipster areas with trendy boutiques, vegan coffee bars, workspaces and new-build housing blocks.

A wildly successful overseas PR campaign was also launched on social media. The message from Copenhagen was that migrants were not welcome and this quickly put off many from even attempting to enter the country.

Denmark banned the wearing of niqabs (pictured) and burkas in 2018 following security incidents

An overhead view of the Sjaelsmark deportation centre for illegal migrants in Denmark

The 48-year-old was chased out of his country for supporting democracy

Signs outside for the Sjaelsmark deportation centre

Cameroonian lawyer Ndam Carlson Agwo pictured in his legal gown and wig

Denmark crucially publishes league tables of criminal convictions based on the perpetrators’ national origins, something the UK does not do, although Home Secretary Yvette Cooper recently agreed to publish such data by the end of this year.

These tables offer incontrovertible evidence that offences, particularly by foreign-born gang members, became an increasing problem after 2015. It is a hard truth but it has bolstered public support for cutting migration.

Last week, an hour’s drive outside Copenhagen, we visited an area that has both a deportation centre, called Sjaelsmark, for migrants on the way out of the country, and a reception holding centre, Sandholm, for those waiting to come in.

The residents of both camps catch buses and bicycle into the nearby town of Allerod during the day, as they wait for Danish officialdom to decide on their futures.

It was in this pleasant town that we met and talked to some of the migrants themselves.

Many were whiling away their time by gathering discarded plastic bottles and drinks’ cans from bins and the street, then taking the rubbish to shops, which weigh what they have gathered and pay them for what they have picked up. The system keeps the town clean and gives the camp residents pocket money ‘for alcohol and cigarettes’, I was told by one young African carrying a bag full of refuse on his way to a shop collection point.

‘It also gives us something to do.’ His day’s haul was worth about £11, he estimated with a grin.

There is no doubt about the migration crackdown’s efficiency. But this has been achieved only by adopting tough measures – and, inevitably, some individuals get caught in the net who perhaps don’t deserve to.

Ms Frederiksen has said she would like to bring immigration numbers down to near zero

New rules came in compelling all newcomers and their children to learn Danish or lose asylum-seeker benefits

People in the ‘hip’ district of Norrebro in Copenhagen – which was once considered a ghetto

Denmark has controlled its numbers by deliberately introducing a hostile environment for migrants

Migrants wave to a smuggler’s boat in an attempt to cross the English Channel, on the beach of Gravelines,in northern France

Denmark publishes league tables of criminal convictions based on the perpetrators’ national origins

An inflatable dinghy pictured carrying migrants makes its way towards England in the English Channel

At a bus stop, we met an Iranian woman of 28 who could not speak Danish or English and had been living in the Sjaelsmark deportation centre for six months.

She cannot be returned to her nation’s tyrannical Islamic regime because it is not deemed to be a safe country, and so she is in limbo. ‘I have nothing. I go nowhere,’ she said.

Another Sjaelsmark resident was an Iraqi Kurd of 23, who arrived in Denmark as a 13-year-old unaccompanied migrant during the massive influx of 2015.

‘I was a child when I walked through the Balkans to get here,’ said the man, who suffers physical and mental health problems. ‘Now I need drugs every day from the doctor to get my head straight. Please can I have a cigarette?’ he asked, putting out his shaking hands for my packet.

Former MEP Soren Sondergard, a Left-wing immigration expert, cited a Syrian family – an accountant father and psychiatrist mother with two children – whom he met recently. They, too, came to Denmark during the 2015 migration wave.

To qualify for citizenship, a migrant has to work for four-and-a-half years in a full-time job. This meant that the couple had to choose which of them should get citizenship in a quirk of the rules.

‘The husband works full-time as a driving instructor. The mother is a part-time kindergarten helper because one of them must care for the children. The result is that only he has been able to get his papers,’ said Mr Sondergard.

Then there is Ndam Carlson Agwo, a 48-year-old, English-speaking Cameroonian lawyer, who has been in Denmark for two-and-a-half years but was earmarked for deportation last month and brought to Sjaelsmark.

Many migrants facing deportation collect plastic bottles to sell for cash to spend in the local shops

Former MEP Soren Sondergard, a Left-wing immigration expert pictured after talking to Sue

Ndam’s room in the deportation centre, with a single bed and small sofa

The Danish Parliament Building in Copenhagen

Carlson, as he likes to be known, is a divorcee with three children who fled to Europe after an arrest warrant was put out for him by Cameroon’s authoritarian government. His crime was to have given legal advice to arrested activists from the ‘marginalised’ English-speaking community who are involved in a civil war against the Francophone government.

Today, Carlson has one small room with an iron bed in the deportation camp. It has a notice outside the door warning of rats. He has been there for a month ‘looking at the ceiling and waiting’.

Every day at 2pm, he goes down to the main building of the huge former military camp and peers at a notice on the wall. It has the names of those who must catch the bus that day for deportation.

‘I was told on Monday I may go at any moment,’ he explained. ‘I have my suitcase packed. I cannot go back to Cameroon.

‘I am in mental agony thinking about it. They will put me in prison and leave me there.

‘I had no idea that liberal Denmark does not help asylum seekers any more, even desperate people like me,’ he added in his fine English accent. ‘It is hard for me to accept that.’

But accept it he must, for Denmark is resolute. The country is living through a remarkable success story, one in which the government believes borders matter and the Danish should choose who comes to live here.

It is a system other European countries grappling with their own immigration problems, including the UK, look at in envy. And who can blame them, as more and more come to our doors and knock – only to be let in.