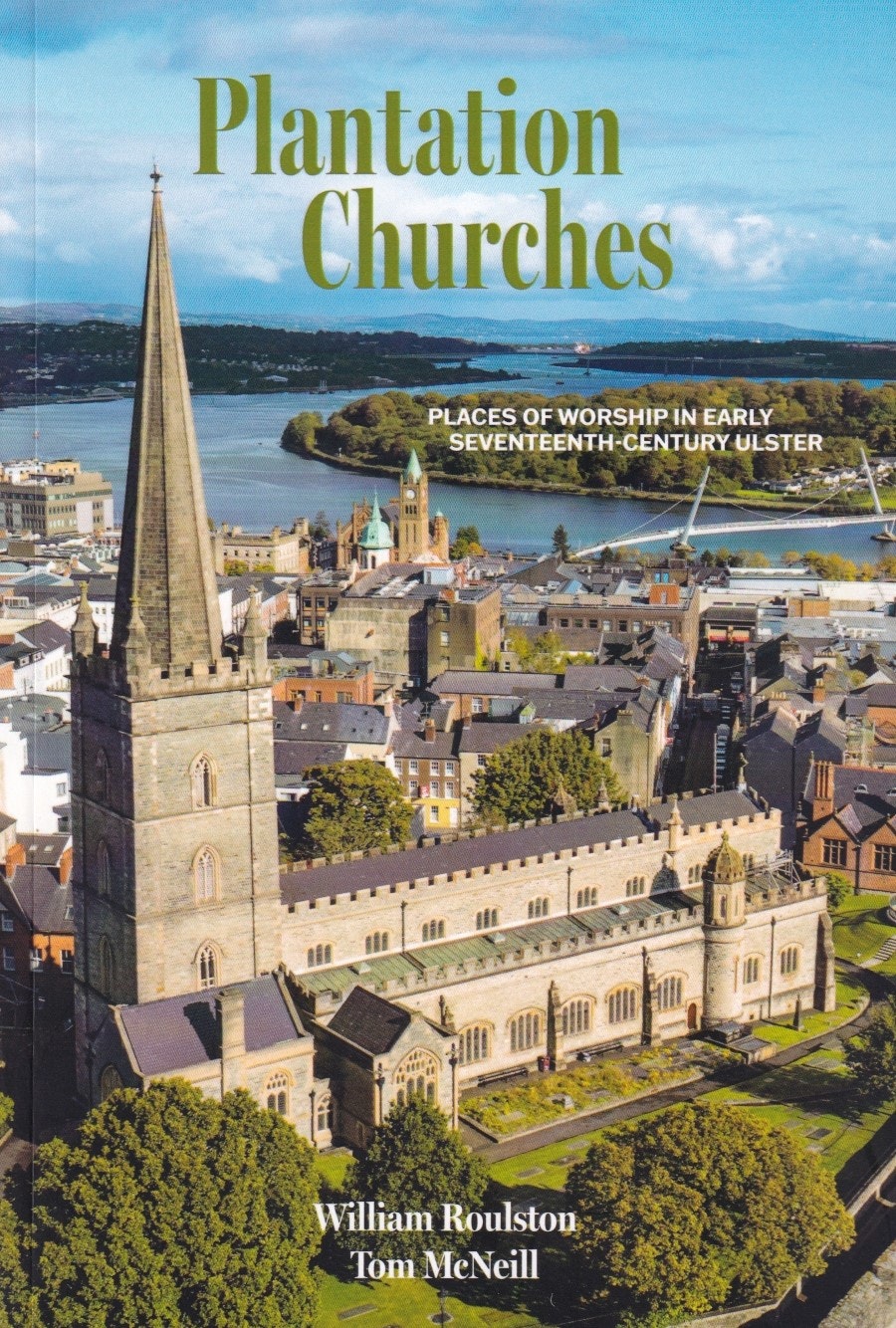

Plantation Churches: Places of Worship in Early Seventeenth-Century Ulster

by William Roulston & Tom McNeill

(Newtownards: Ulster Historical Foundation, 2025)

ISBN: 978-1-913993-73-3 (softback)

180 pp., 38 col. & 12 b&w illus., with 3 b&w maps

£22.99

The early 17th-century scheme of the Government of King James VI & I to colonise the New World, in what was known as the Plantation of Virginia, had commenced, when in 1607 huge tracts of land in the Province of Ulster in Ireland became escheat to the Crown following the “Flight of the Earls” (the former Gaelic Chieftains O’Neill and O’Donnell and their retainers and families) to the Continent.

This emergency, not unconnected with the security of the Kingdoms, led to the “Plantation” of Ulster to be carried out by numerous individuals, but in the case of a considerable area lying west of the River Bann, bounded by the sea and Lough Foyle to the north, by County Donegal to the west, and by Counties Tyrone and Armagh to the south, settlement of that was forced on the then 55 livery Companies of the City of London to colonise. The Londoners were extremely reluctant to get involved, but were leant on very heavily by the Government, and so, with threats of fines, imprisonment, or worse, grouped themselves into 12 associations, each led by a “Great Company”, in order of precedence Mercers, Grocers, Drapers, Fishmongers, Goldsmiths, Skinners, Merchant Taylors, Haberdashers, Salters, Ironmongers, Vintners, and Clothworkers. Each Great Company contributed with “Associated Companies”, apart from the Grocers and Merchant Taylors, who remained without Associates, financing the development of their Estates entirely by themselves: the Vintners, however, had 9 Associates; the Ironmongers 6; and the Fishmongers 5. These 12 groups were each allotted a “Proportion” of the land, which they were obliged to “plant” with loyal settlers, and build fortified manor-houses, each with a “bawn” (a fortified court with flanking towers at each corner for defence), and a settlement with houses as the “capital” of each Proportion.

Supervising the whole business was The Honourable The Irish Society, consisting of senior men of the City of London, and it was charged with building, fortifying, and populating a new walled city and a fortified town, with places of worship in both. A Deputation from London was sent to inspect the lands under armed guard, but the existing County of Coleraine was judged too limited in too many respects, so the City demanded land on the far side of the River Foyle in County Donegal to provide the Liberties of the new city, territory on the opposite side of the Bann in County Antrim to provide the Liberties of the new town of Coleraine, and a chunk of County Tyrone containing virgin forest to provide wood for the enormous works of construction required.

Thus the County of Coleraine disappeared, and its enlarged successor came into being as the County of Londonderry. It should be noted that there never, at any time, was an Irish “County Derry”, despite the delusions of announcers on the BBC (notably Radio 3) and others, although the Diocese always was and is that of Derry (to which Raphoe was later attached). The new city was named Londonderry in its Charters, and was the last fully fortified walled town to be built in all Europe, the works carried out under London masons. Sir Josias Bodley (c.1550-1617), Director-General of Fortifications and Buildings in Ireland, brother of Sir Thomas Bodley (1545-1613 — founder of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford), approved (and probably helped to prepare) plans for fortifying Coleraine by constructing a thick earthen rampart some 4 metres wide, with a deep ditch, around the fledgling settlement.

It was also essential to provide places of worship for the Anglican Church, and ensure there were clergy to serve them. Thus many old churches had to be repaired or even rebuilt, and new ones erected. The new city of Londonderry (the governance of which was modelled on that of the City of London, hence the “Guildhall” for municipal business and ceremonies) was also to be provided with a cathedral for the Bishop of Derry, and this was completed in 1633 by William Parrott (fl.1622-42), who seems to have been closely connected with the Merchant Taylors. Parrott worked under the general supervision of Captain Sir John Vaughan (1564-1643), military commander of Londonderry until his death, who was probably the leading personality in the creation of the city from c.1608. A tablet in the cathedral tells us that “If Stones could speake then Londons Prayse should sounde who built this Church and Cittie from the Grounde Vaughan Aed”, and dated 1633 in the 9th year of the reign of Charles I.

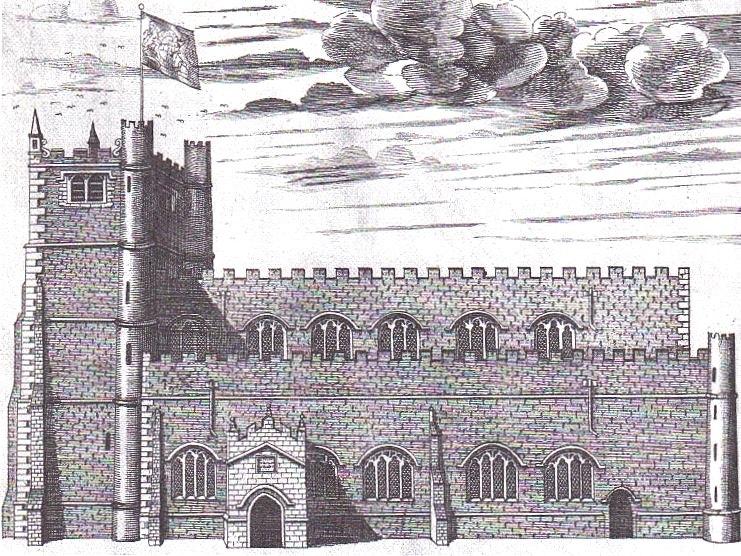

Terrible damage had been done to ecclesiastical buildings in Ireland. In the 1530s there had been various enactments in the Irish Parliament for the suppression of religious houses, and in 1541 under 33 Hen. VIII, c.1, Henry VIII was declared King of Ireland (the Bill was presented in Irish as well as in English: prior to that time, the Kings of England had only been Lords of Ireland). Thereafter suppression of monasteries, friaries, and other establishments proceeded apace, the Irish, despite their supposed allegiance to Roman Catholicism, also joining in the general looting and destruction of the architectural fabric to be used as quarries for new buildings. The closing years of Elizabeth’s reign saw the Nine Years’ War, which culminated with the landing of a Spanish Army to support the Irish in County Cork in 1601 and the subsequent defeat and submission of the Irish Lords and their Spanish allies to English forces. Those upheavals did not favour the survival of ecclesiastical buildings, as a drawing by Richard Bartlett (fl.1595-1603) of St Patrick’s Cathedral, Armagh, of c.1602 rather powerfully shows. To be a cartographer in Ireland was a very dangerous occupation: Bartlett, for example, was tortured by the Irish in Tirconnell, who then “took off his head, because they would not have their Cuntrie discover’d”.

It is interesting that the style of the new church in Londonderry was still Gothic, owing much to the conservative tradition of the Worshipful Company of Masons of the City of London which was not to succumb to the imported Classical styles to any great extent until the Restoration period and the ascendancy of Sir Christopher Wren (1632-1723). It is certainly interesting that the architectural style of the new church was deliberately backward-looking, far-removed from the Palladianism favoured by the Stuart Court at the Queen’s House, Greenwich (1616-35), the Queen’s Chapel, St James’s (1623-5), and the Banqueting House, Whitehall (1619-22), all by Inigo Jones (1573-1652), and all associated with King Charles and his Roman Catholic Queen. It should be remembered that architectural styles had profound associations and resonances at one time, and it is not insignificant that Palladianism did not re-emerge as a favoured style until the advent of the House of Hanover in 1714, when the Second Palladian Revival exercised a veritable tyranny of taste during the reigns of the first Georges. That there was a political strand in the Second Palladian Revival of the 18th century cannot be doubted.

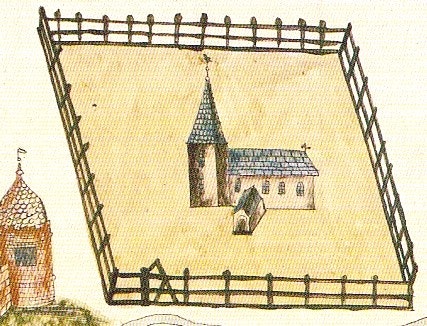

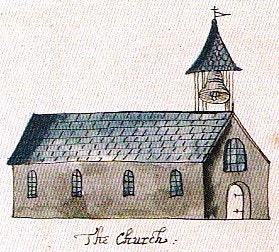

Thomas Raven (c.1572-1640) was rather luckier than Bartlett, and carried out a marvellous survey of the Londoners’ properties in County Londonderry 1622, giving us some idea of what the settlements actually looked like. Many houses were timber-framed, and the churches were shown, often very basic single-cell structures, with minimal architectural pretensions. I give two examples from Raven’s survey here, the first on the estate of the Vintners’ Company at “Balleaghe” (Bellaghy, now better-known for its associations with Seamus Heaney [1939-2013], which was known for a time as “Vintnerstown”), and a second on the estate of the Merchant Taylors’ Company at Macosquin, with a pretty little timber belfry on a simple rectangular preaching-box with semicircular-headed window- and door-openings. Strangely, the authors of the book, themselves distinguished historians, have mistakenly identified this last image as the church at Muff (now Eglinton) on the estate of the Grocers’ Company, but that is incorrect. It seems that captions were inadvertently transposed.

The church of St Mary, of the parish of Camus-juxta-Bann at Macosquin, much altered from the time of the Raven survey, now has a tower and a rudimentary chancel, but parts of the walls are survivors from the pre-Plantation building there, and there is a lancet-opening on the north side (almost invisible now) which may have been a lychnoscope, or “leper’s squint” in what had been the monastic church of a Cistercian foundation known as the Abbey of the Virgin of the Clear Spring, an establishment dating from c.1172. A plan of the layout of the settlement at Macosquin of c.1615, probably by a surveyor named Costerdyne, shows the church set at an angle to the road before it, and that is still obvious even today, so it is evident that the Londoners sensibly made use of what surviving ancient fabric was available when erecting or repairing churches.

Of course there were many individuals who received grants of land in Ulster, including Hugh Montgomery of Ayrshire (c.1560-1636—1st Viscount Montgomery of the Great Ards from 1622), who managed to get a foothold in County Down 1606, just before the Jacobean Plantation scheme was even mooted. He carried out works at the former friary at Newtownards, repairing the church for worship, and adding his own residence to it. Among the marks he added is the very Scots door-surround to the tower, and the thumping funerary monuments within the building.

Some idea of a simple early 17th-century Ulster church can be gleaned by studying St John’s, Islandmagee, County Antrim, possibly erected under the ægis of Sir Moyses Hill (before 1555-1630), who held a lease of the peninsula from Sir Arthur Chichester (1563-1625). It is a charming little Jacobean church, snugly set in a walled graveyard, set high with views west over Larne Lough, with five-light windows set in the east and west ends, and three-light windows in the side walls. Part of the fabric may date from the 1590s. Also closely connected with individual patronage was Derrygonnelly Old Church, County Fermanagh, erected in 1627 by Sir John Dunbar (1606-66): the showy west door-surround, featuring diamond-pointed rustication, has above it the arms of Dunbar and his wife, Jane Katherine Graham.

One of the more interesting churches associated with English and Scots settlers is the Donaghmore parish church of St Michael, Castlecaulfeild, County Tyrone, which was erected in the 1680s under the auspices of the redoubtable Revd George Walker (1643×8-90), who had been appointed Rector of Donaghmore in 1674, and who was later closely associated with the defence of Londonderry during the famous Siege, and later killed at the Boyne when going to the aid of the mortally wounded Frederick Herman von Schönberg (1615-90 — 1st Duke of Schomberg from 1689). However, the building contains elements from the earlier church which had been erected by Sir Toby Caulfeild (1565-1627 — 1st Baron Charlemont from 1620) around 1622, but was destroyed in the ferocious uprising that began in 1641 which obliterated a great deal of the fabric created as a result of the Plantation. Among those early 17th-century re-set elements is the extraordinary traceried window, a survival of Gothic, but very much of its time too.

Although the Plantation heralded the end of Gælic Ulster, and the removal of the old Gælic system of chieftains, one great family managed to remain in place, and does so to this very day: they were and are the MacDonnells of Antrim. Randal MacSorley MacDonnell (d.1636 — 1st Earl of Antrim from 1620) managed to avoid the embroilments which caused the flight or arrest of most of the Ulster Chieftains by 1610, and ingratiated himself with The Honourable The Irish Society and the Stuart Court, so much so that Parrott designed a major enrichment of his chapel at Dunluce Castle, where the chapel was kitted out in considerable magnificence and his priests provided with gorgeous vestments, all at some expense too. MacDonnell also built or repaired several churches in his domains for the use of the Anglican Church of Ireland, while also restoring the Franciscan friary at Bonamargy, where he himself was to be entombed. Indeed the building was used by the Third Order of Franciscans until the middle of the 17th century, despite the legal prohibitions, threats, and determined clamp-downs, all of which demonstrate the immense clout held by a powerful Roman Catholic magnate owning enormous tracts of land. Such a balancing-act required extreme cunning, especially in such fraught times. The friary was also used as a burial-place for the McNaghtens, of which family John McNaghten was secretary to Randal MacDonnell. Today, the former friary ruins lie near the main road to Ballycastle from the south, beside a golf-course, so the site has lost much of its atmosphere, but is still well worth a visit.

A book about Plantation churches is long overdue, and this is a worthy, scholarly start, but the subject deserves greater coverage, many more illustrations, better maps (finer draughtsmanship and the intelligent use of colour would have greatly improved the rather meagre offerings printed here), and a more lavish presentation, for there are many riches which could be revealed, as I well know, having been over much of the ground myself. Let us hope Drs Roulston and McNeill can be persuaded to proceed in that direction.

Many years ago I wrote short monographs on the estates of the Fishmongers’ and Drapers’ Companies, and a London reviewer expressed the hope that I would write a major tome on the estates of all the Companies and the general involvement of the City as a whole. I started to do this in the late 1970s, and after much labour and time slogging it out in Company archives and in the records held at Guildhall Library, City of London, I reckoned I had the makings of a huge book. I prepared a carefully composed outline and submitted this to a respected University Press. I was amazed and enraged when I had a curt letter informing me that Forestry in Northern Ireland would not be of interest to that august institution. They had obviously not even bothered to read my outline, merely spotting the word “Plantation”, and jumped to absurd conclusions. Doubtless the “experts” of that University Press thought the Plantation of Virginia was something to do with cigarettes.

Eventually I managed to persuade Phillimores of Chichester to publish my work, and it appeared in 1986 as The Londonderry Plantation 1609-1914: The History, Architecture, and Planning of the Estates of the City of London and its Livery Companies in Ulster, a massive book which, though out of print, now fetches high prices, and which received very positive reviews when it first appeared. Some years later I was approached by The Honourable The Irish Society to write a book about that organisation, which still exists to run what is left of London’s holdings in Ulster: the result was The Honourable The Irish Society and the Plantation of Ulster; 1608-2000: The City of London and the Colonisation of County Londonderry in the Province of Ulster in Ireland. A History and Critique, which Phillimores also published in a very fine edition in 2000.

I have always taken the view that careful, well-researched, dispassionate history based on sound evidence is the best antidote to destructive mythologies, uninformed untruths, and destructive narratives. Given the fact that invincible, bucranial ignorance is now well-entrenched in University Presses, in Universities themselves, and in almost every institution imaginable, shedding light where there is darkness gets more difficult by the day.