A non-hormonal male contraceptive that prevents sperm from leaving the body remains effective for at least two years, groundbreaking research suggests.

The implantable contraceptive, known as Adam, is a gel that is injected underneath the scrotum.

The Virginia-based company behind the product, Contraline, says this approach offers a convenient alternative to existing methods such as condoms and vasectomies.

The hydrogel is designed to break down in the body after a set period of time, restoring fertility.

Contraline has released findings of its study of 25 men that showed the gel successfully blocked the release of sperm for two years in the two participants who saw out the entirety of the trial.

It said no serious adverse side-effects had been recorded though the results of the study do not include data on the reversibility of the implant.

Founder Kevin Eisenfrats, told the Guardian: ‘This is really exciting because our goal since day one has been to create a two-year-long male contraceptive – that is what the demand is for.

‘And we have the first data to show that that’s possible.’

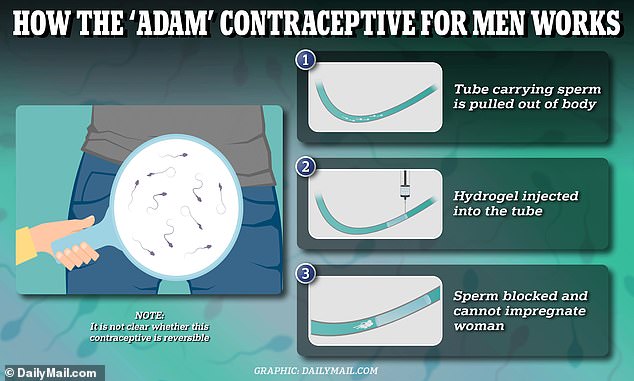

The above graphic demonstrates how the hydrogel blocks sperm from exiting the body, helping a man avoid getting a woman pregnant. Doctors are not sure whether it is reversible, but have shown the gel is effective at blocking sperm for at least two years.

A male contraceptive pill has been years in the making. Today, men have condoms or withdrawal as the only two practicable birth control options.

Researchers recruited 25 men at various points over the two year trial and injected them with the contraceptive.

The implant was inserted via a minimally invasive procedure into the vas deferens, the tube that carries sperm from the testes, under local anaesthetic.

Doctors then made a small incision underneath the scrotum to expose part of the vas deferens.

They then injected the tube with the gel before reinserting it into the body and stitching the incision closed.

All participants were monitored after the procedure and no serious adverse events were reported.

All participants also experienced a drop in sperm count, indicating the contraception was effective in preventing sperm from leaving the body.

Eisenfrats heralded these results as a ‘great proof of the concept’, with more results expected to follow.

Adam is not the first experimental contraceptive that acts by blocking the function of the sperm ducts.

This approach means that men can still experience ejaculation, because the fluid for this is produced in another area.

Eisenfrat explained, however, that some of the other male-contraceptives currentlyon trial use materials that do not break down in the body, resulting in infertility.

There are, however, concerns that such implants could cause scaring of the sperm ducts and lead to permanent sterilisation.

Results from the Adam trial have not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal and do not include real life data on whether the injection can prevent pregnancy.

According to Eisenfrats, the hydrogel has been shown to break down over time in animal trials, revealing a short period of efficacy.

‘The way to think about this is sort of like the IUD [intrauterine device] for men’, the chief executive told The Guardian.

He added that after a two-year period, men could decide whether to get another implant.

The team are also reportedly working on a procedure to enable ‘on-demand reversal’, which would use at-home sperm tests to check whether contraceptive was still effective.

For women, traditional non-hormonal intrauterine devices, also known as a copper coil or IUD, last for five to ten years, depending on the type of device used.

After an IUD is removed, fertility levels are expected to return to previous levels right away.

Some women opt for an intrauterine system, or IUS, which uses the release of the hormone progestogen to stop pregnancy.

The hydrogel designed by Contraline does not interfere with a man’s hormones.

While the results of the Adam show promise, some experts have raised concerns over how reversible the gel is and have warned that sperm could find a way around the blockage, resulting in an unplanned pregnancy.

Professor Richard Anderson, an expert in hormonal male contraception at the University of Edinburgh, warned that at present it remains unclear how long a single implant lasts and it is yet to be shown that it can be removed.

A major hurdle to male contraceptives, expert say is that they would need to interrupt the production of millions of sperm made every day.

Most of the male birth control possibilities undergoing clinical trials target testosterone, blocking the male sex hormone from producing healthy sperm cells.

Doctors say, however, the testosterone-blocking action can trigger weight gain, depression and increase cholesterol.

The female contraceptive pill — which contains synthetic versions of female hormones estrogen and progesterone— has been linked with similar side effects.