Like millions of Britons of a certain age, my childhood was made more joyous by Johnny Morris, the presenter of the TV programme Animal Magic.

A farm manager with an extraordinary gift for storytelling and mimicry, Morris’s talent was spotted by a BBC producer (in a pub, apparently). And in 1962, the corporation found the perfect formula, in which Morris played the role of a keeper in Bristol Zoo who vocalised what the animals were ‘saying’, while brilliantly making the words synchronise with the filmed facial movements of the creatures.

It was all glorious nonsense, though it somehow seemed completely real to me, as it must have done to countless other children of the era.

But after 21 years, the BBC dropped the series, in part because this sort of anthropomorphism became frowned upon, as, indeed, did the idea of animals in captivity. In a sense, David Attenborough replaced Johnny Morris.

I have been thinking about this part of my childhood because last week Google DeepMind announced that it was putting its phenomenal computing power and AI programmes behind a project – DolphinGemma – to enable humans to understand and even share the ‘language’ of those marine mammals, with their signature whistles, squawks and buzzes.

Google DeepMind says it will decode these patterns in order to ‘establish a shared vocabulary with the dolphins for interactive communication’.

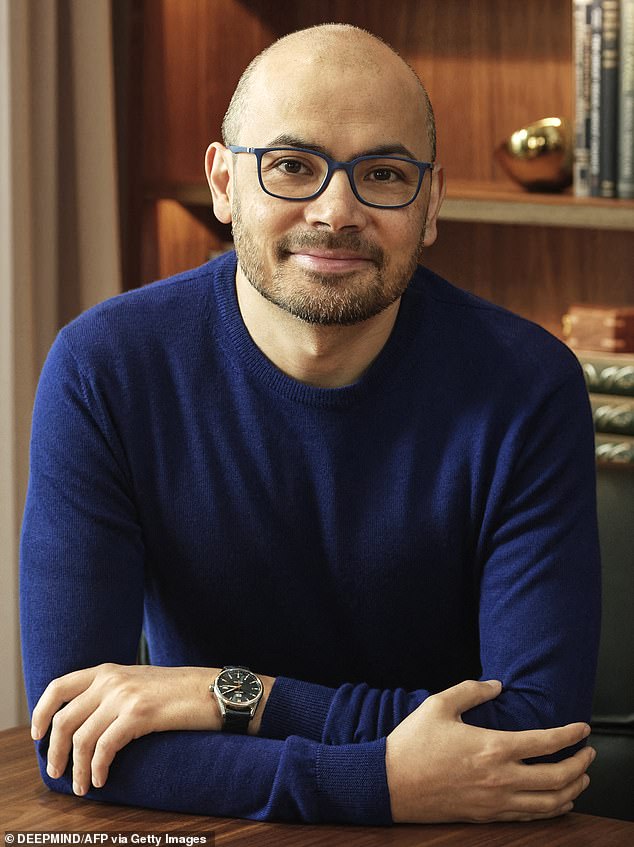

The founder of DeepMind, Sir Demis Hassabis – born and bred in London – tweeted: ‘In the future soon, we will be able to communicate with many intelligent animal species . . . can’t wait to better understand what my dog is saying!’

I know Demis quite well and have learned that when he puts his resources behind something, it has astonishing results. For example, when in 2020 his AI team created AlphaFold, which cracked the fiendishly difficult problem of predicting how proteins would fold into 3D shapes, I emailed him to suggest this might one day win a Nobel Prize. Last year, Demis was, indeed, awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry (and that richly deserved knighthood).

Johnny Morris, the presenter of the TV programme Animal Magic, could talk to the animals to the joy of countless children in the 1960s

DeepMind, founded by Sir Demis Hassabis, announced it is putting its AI programmes behind a project called DolphinGemma to enable humans to understand the marine mammals

An uncomprehending machine will be able to talk dolphinese to dolphins, and the dolphins will be able to talk back

All the same, I also appreciated the humour of the person who responded to Demis’s tweet, with a cartoon from Gary Larson (creator of The Far Side).

This showed a white-coated boffin with a weird device over his head and ears and the explanatory words: ‘Donning his new canine decoder Professor Schwartzmann becomes the first human being on Earth to hear what barking dogs are actually saying.’

All the voice bubbles from every single barking dog, across the neighbourhood, are saying the same single word: ‘Hi!’ At least ‘Hi’ is a word we can all understand. But philosophers have a more fundamental issue with the idea of establishing a common language with animals.

This was put in characteristically gnomic form by the Austrian-born British philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein in his posthumously published work Philosophical Investigations: ‘If a lion could speak, we could not understand him.’

What Wittgenstein meant was that language – how we humans communicate with each other – is based on shared concerns, experiences and culture.

And, he suggested, a lion’s world is so radically different from ours, that – even if we could ‘translate’ its words – we would be completely unable to understand what it was trying to ‘say’.

Or, to use Wittgenstein’s own phrase, there would be no real communication because lions do not have ‘any conceivable share in our world’.

It is significant, I suppose, that this brilliant man, who still exercises a mesmerising power in his field, chose a wild animal.

Demis’s reference to his pet dog will resonate with many, because we do, after all, seem to have pretty good communication with ‘man’s best friend’. Although I did not feel that there was much of a meeting of minds with our dog Luna when, last night, I and my daughter repeatedly failed to get her to come back indoors after her evening stroll, even when offering all manner of treats.

Since Wittgenstein (1889-1951) is not around, I raised what Demis and Google DeepMind have claimed with some of our leading philosophers who work in this field.

Professor Edward Harcourt of Oxford University pronounced himself sceptical about the dolphin project, after noting that ‘people do already talk to animals and they understand, as most obviously with dogs’.

But, as for the presumed ability of Google’s Large Language Models to decipher the whistles and clicks of dolphins, he said: ‘Where does that get us? An uncomprehending machine will be able to talk dolphinese to dolphins, and the dolphins will be able to talk back, but does that further our understanding of what is going on? I don’t see why it would.’

And who better to contact than Professor Constantine Sandis, author of Wittgenstein On Other Minds. He sent me the following: ‘It is tempting to think that animals talk to themselves in their own languages and that if only we could decode them, we could come to communicate with them in a Doctor Dolittle kind of way.

‘And if such communication is possible, then surely AI can help us achieve it. If AI can offer up translations of spoken human languages, then why should it not also be used to decode those of animals?’

But Professor Sandis then pours cold water: ‘While AI is vital in helping us to understand animal behaviour and the reasons for it, if only because of the sheer speed with which it can organise huge volumes of data to better detect patterns between animals’ sounds and movements in their interactions with us, you’d be barking mad to think that AI can translate pet sounds into human languages.’

However, farmers (as Animal Magic’s Johnny Morris had been) will surely hope that Google DeepMind does not start to turn its attention to ruminants and the like.

Few passages of literature can have been more powerful in converting readers to vegetarianism than that in Douglas Adams’ science fiction comic novel The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy, where Arthur Dent is taken by his extraterrestrial mates to the Restaurant at the End of the Universe.

There, they meet the meat. A large cow approaches the table, sits back on its haunches and says: ‘Good evening. I am the main Dish of the Day. May I interest you in the parts of my body?’

Arthur is appalled: ‘That’s absolutely horrible . . . the most revolting thing I’ve ever heard.’

And when Arthur tells Zaphod Beeblebrox, ‘I just don’t want to eat an animal that’s standing there inviting me to’, he gets the unanswerable retort from his companion: ‘Better than eating an animal that doesn’t want to be eaten.’

Obviously, this is fiction, and Adams’ invented ‘animal-speak’ was as misleadingly anthropomorphic as Johnny Morris’s on Animal Magic.

In a sense, those who portray animals as exactly like us are as unimaginatively human-centric as those who cruelly suppose that only we have feelings and that therefore creatures can be treated like inanimate objects.

On the other hand, I can’t think that there will ever be a future in which humans learn to speak ‘dolphinese’ – or, if we did, that the dolphins would see any porpoise to it.