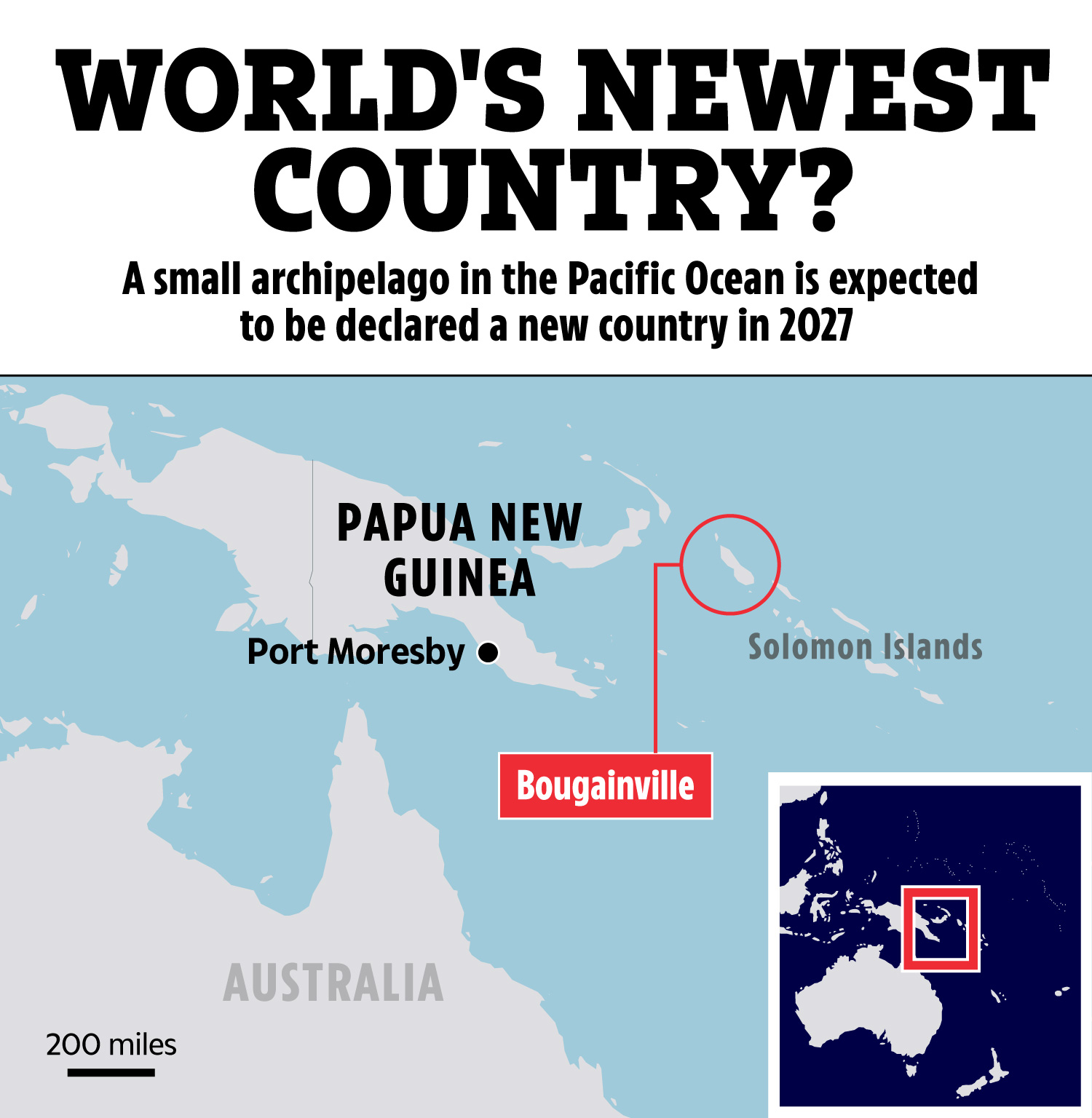

A SMALL archipelago in the Pacific Ocean could soon become the world’s newest country – and a major geopolitical flashpoint.

Currently part of Papua New Guinea, the people of Bougainville voted overwhelmingly for independence back in 2019.

But Bougainville’s path to independence has been long and difficult, with many political and economic obstacles still blocking the way.

The islands are home a potentially lucrative copper mine, and its strategic location in the Pacific makes it a point of interest for regional powers.

A leading expert on the region has said that Papua New Guinea is deeply reluctant to let go of the islands despite the historic vote.

Australia‘s former High Commissioner to Papua New Guinea Ian Kemish told The Sun: “The simple fact is that the national parliament has no wish at all to see Bougainville go.

“Both sides have been avoiding confrontation, but there’s a lot of tension left in this.”

The islands were rocked by a lengthy war over its status in the late 20th century that turned into the region’s deadliest conflict since World War II.

Leading figures in Bougainville want the islands to have full independence by 2027.

This will have to be ratified by the Papua New Guinea parliament, and getting this approval has proved to be a sticky process.

But the region’s President Ishmael Toroama, a former rebel fighter, has insisted that independence for Bougainville is a matter of when, not if.

“Bougainville is for independence. It is only a matter of time,” he said this year.

The islands can be found east of mainland Papua New Guinea – which itself is just north of Australia.

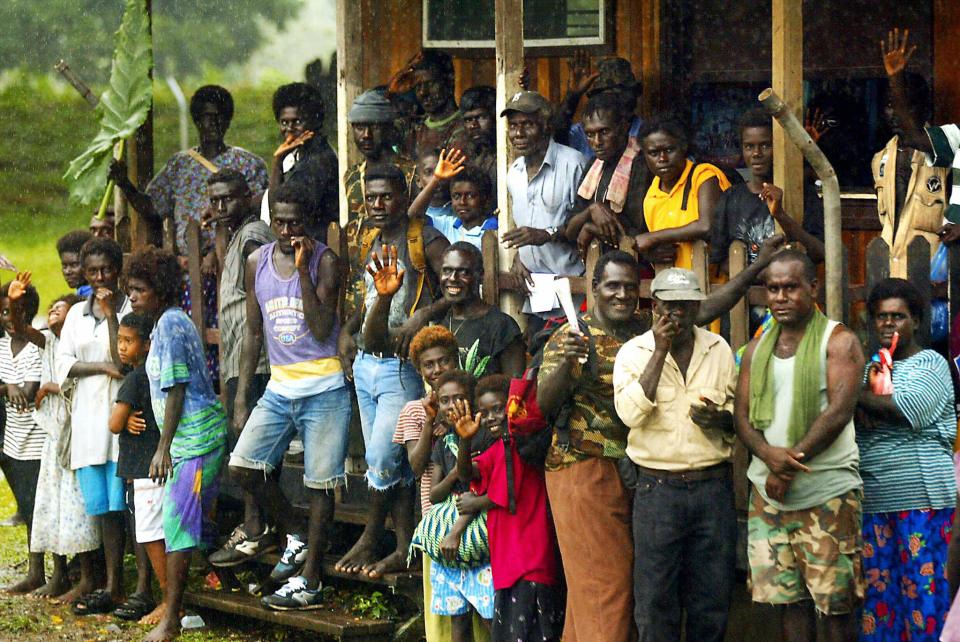

Home to around 300,000 people, Bougainville will have one of the world‘s smallest populations once it becomes a country.

Running a booming economy would be one of the key challenges an independent Bougainville will face, Kemish told The Sun.

The Panguna mine, a focal point in the brutal civil war that raged between 1988 and 1997, is often cited as a potential asset – although it has been closed for decades.

Kemish said: “For Bougainvilleans, it will be extremely hard to resurrect that mine.

“And they’d need that mine or something else to run an economy.”

Bougainville’s copper reserves are estimated to be worth billions of dollars.

Not only this, but the island’s strategic location could make it an ideal spot for a US military base as Washington seeks to contain China‘s expansion.

For Toroama, there’s a deal to be made.

If Donald Trump could be persuaded to throw his weight behind the stalling independence process, Bougainville could give the Americans a golden offer.

“Well, the Panguna mine is here. It’s up to you,” Toroama is reported to have said.

However, Kemish is sceptical that the Trump administration would show any interest in the region.

“I don’t really believe that it’s going to be of much interest,” he told The Sun.

“But there is a broader point. From a geopolitical point of view, an independent Bougainville could be useful to either the US or China.”

The territory is made up of several islands, the largest of which is Bougainville Island itself.

The Soloman Islands, another small Pacific archipelago nation, lie just to the east of Bougainville.

At 3,623 square miles, the country would be one of the world’s smallest upon its independence – just slightly larger than Cyprus.

Papua New Guinea became independent from Australia in 1975, with Bougainville becoming an autonomous region of the country the following year.

An independence referendum was promised to Bougainville in 2001 as part of a peace agreement that brought the bloody civil war to an end.

Bougainville had declared independence in 1975 as the Republic of the North Solomons, but this was internationally unrecognised – and the territory was absorbed into Papua New Guinea the following year.

But tensions quickly flared up on the islands, with the mine representing a key point of contention.

“People remember the conflict and they don’t want to go back there,” Kemish told The Sun.

“No one is quite sure how many people died, but it’s certainly thousands.”

It would be nearly another two decades after the fighting stopped before the landmark referendum was held.

Bougainvillians were offered either full independence or greater autonomy within Papua New Guinea in the 2019 vote.

An overwhelming 98 per cent of voters opted to put the islands on the path to statehood.

New countries don’t emerge often. The most recent freshly independent nation to join the UN was South Sudan, which broke away from Sudan in 2011.

Bougainville timeline

1975 – Bougainville declares independence as the Republic of the North Solomons

1976 – Bougainville is re-absorbed into Papua New Guinea

1988 – Civil war breaks out

1997 – Fighting comes to an end after mediation

2001 – Peace deal reached, including commitment to a referendum on independence

2019 – Bougainville votes for independence in the referendum

2027 – The target date for independence

The 2019 Bougainville referendum was not legally binding on the government of Papua New Guinea, meaning it is not necessarily obliged to follow through.

Independence would have to first be approved by Papua New Guinea’s parliament, and this is still yet to be granted.

Kemish told The Sun “I think there’s an underlying concern that if they let one bit go, other bits will want to follow.

“They feel the territorial integrity of the nation is at stake.”

An agreement called the Era Kone Covenant outlining steps towards independence was reached between the authorities of Papua New Guinea and Bougainville in 2022.

However, the timetable set out in the covenant included ratification of independence by 2023, which has not come to pass.

This throws the 2027 finalisation deadline into doubt.

The Bougainville and Papua New Guinea governments are reported to have been at odds over how the ratification process should work.

One sticking point is believed to be whether the parliamentary vote should require a simple majority to pass, or a two-thirds supermajority.

Advocates of independence fear the Papua New Guinea parliament is stalling.

While the islands may have potential with their natural resources, more than 87 per cent of the islanders work in agriculture – according to the Australian High Commission in Papua New Guinea.

Its strategic location and resources would likely draw attention from both China and the US as they look to further their interests across the Pacific.

“On one hand, the national government doesn’t want to push this to an outright no,” Kemish said.

“But on the other hand, the Bougainvillieans don’t feel ready to unilaterally declare independence.”