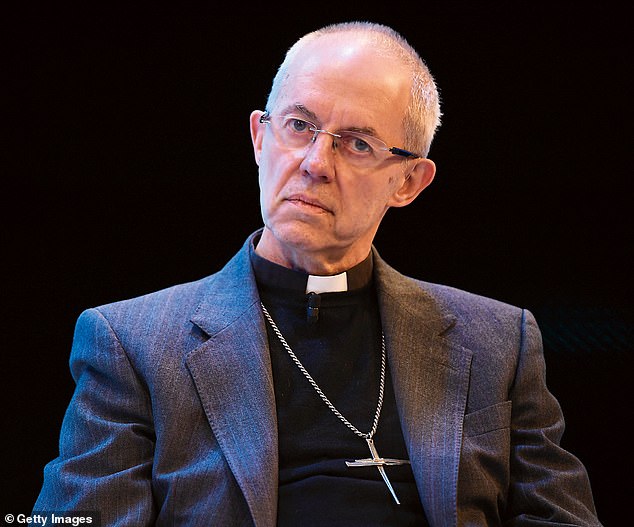

The Bishop of Newcastle, Dr Helen-Ann Hartley, is quietly furious. I’m interviewing her immediately after the former Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby spoke to the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg, telling her he forgives the serial sex abuser John Smyth, the man who lost him his job.

It was Hartley who last November initially called for Welby’s resignation – the only bishop out of 108 to do so – after he was criticised in a report into the Church’s handling of Smyth, a British barrister and Christian camp leader who abused boys and young men in Britain and Africa over three decades. Now, barely four months later, Welby is, in Hartley’s words, ‘attempting to begin some rehabilitation process’.

‘I think it was baffling, and yet again it’s caused trauma to those abused,’ she says.

‘I know that because I’ve been contacted by a number of victims and survivors, not just of Smyth but of other cases of Church abuse.’

Dr Helen-Ann Hartley, Bishop of Newcastle, in December 2024

And what about Welby publicly forgiving Smyth, who died in 2018? Surely as a Christian he had to agree to forgive the abuser? ‘I think that’s for victims of Smyth to do. That’s for god,’ she says. ‘It may be the Archbishop’s opinion, but it’s one that he should have kept to himself.’ It is plain speaking like this that has made Hartley possibly the most controversial bishop in the Church of England.

The Bishop’s House, in the Gosforth area of Newcastle upon Tyne, is distinctly un-palace-like: there’s a short tarmac drive up to a nondescript side door in what was a 17th-century farmhouse. This is where Hartley has her office and there she is by the door as my taxi pulls up. She is dressed simply in slacks and a cardigan, and looks younger than her 51 years. She is almost showily unshowy, eschewing even the dangling cross that some people of the cloth like to display on occasions.

What brought her to national attention was her reaction to the publication last autumn of the Makin Review. It detailed how John Smyth, who ran Christian camps in the UK and Zimbabwe and was ‘the most prolific serial abuser to be associated with the Church of England’, used his position to beat and strip naked more than 100 children and young men.

The report criticised Archbishop Justin Welby, who worked at the camps as a teenager, for not doing enough to hold to account those responsible for the Smyth cover-up.

‘Makin was overwhelmingly horrific,’ says Hartley, as we sit in her cluttered office. ‘People’s lives have been forever impacted and it almost makes you want to walk away from the Church. It shone a light into the abyss. And once you’ve looked into the abyss, you know you’ve changed for ever. I saw the depths of the problem of religion, while at the same time, on a personal faith level, holding on to the hope of religion.’

It seems preposterous that she – one of just nine female bishops, the youngest Diocesan bishop in the Church, who had been in her role for barely a year – was the only one brave enough to speak out against the lack of accountability at the top. But she was.

Following the report’s release, in an interview with the BBC’s religion editor Aleem Maqbool, she called Welby’s position ‘untenable’. ‘I think, rightly, people are asking the question: “Can we really trust the Church of England to keep us safe?”’ she said to Maqbool. ‘And I think the answer at the moment is ‘‘no”.’

‘What you need to know,’ she tells me, ‘is that [after the report came out] there were lots of phone calls and WhatsApp messages flying around between bishops.’ Those bishops said they thought, like Hartley, Welby should step down. ‘So I thought, if I actually say he should resign, I know that there are XYZ bishops who will come out and say, “We support Bishop Helen-Ann’s intervention.”’

But that didn’t happen. ‘There was a wall of silence,’ she says. That must have felt lonely, I say. ‘It did. I hadn’t naively expected “well done” or “thank you”, but any sense of support was from other people, not from my episcopal colleagues.’

A Church Times columnist subsequently accused Hartley of making a naked bid to be Welby’s successor. She sighs. ‘That wicker basket thing over there in the corner is stuffed full of letters and cards,’ she says. Most of it is support, she adds, ‘then there’s, “You’re doing Satan’s work and obviously you’re doing it for your own advancement.”’

The controversy is the second that Hartley has confronted. The first concerned the former Archbishop of York, John Sentamu, who lived and still preached in the diocese.

A victim of historic abuse at the hands of the Reverend Trevor Devamanikkam in Bradford in the 1980s had come forward in 2013 to tell Sentamu about his ordeal. Sentamu, in the Church’s words, ‘failed to act’.

Devamanikkam took his own life in 2017 while awaiting trial on charges of sexual abuse. After the Church’s 2019 inquiry criticising Sentamu, Hartley took action. ‘For me there were no qualms. I had to ask him to step down from public ministry.’

The Archbishops of Canterbury and York, Welby and Stephen Cottrell, did not agree. Towards the end of last year, Hartley received an email containing a joint letter from the two Primates. ‘It said that we need to find a way to get Sentamu back in to public life, in to ministry. And that letter didn’t sit well with me.’ In fact, she saw it as coercive.

She has previously spoken of the culture of ‘power, privilege and entitlement’ at the top of the Church and the operation of ‘old boys’ networks’ invested in protecting the institution. Did she read that letter as saying, ‘you need to do this for the sake of the club’?

I ask. ‘Yes’, she says. And it’s a club she clearly thinks needs to be broken up.

Hartley came to the Church through her mother and father, both of whom were priests. She was born in Edinburgh, the daughter of a minister who was the son of a minister, who was himself the son of a minister. She took degrees in theology at St Andrews University and Princeton Theological Seminary, followed by a master’s and then a doctorate of philosophy at Oxford. She imagined a career in academia. Then, to no one’s surprise but her own (she hadn’t wanted to be seen as a nepo priest), she told her parents she wanted to be a vicar. She was ordained in 2005.

It certainly felt like even more of a boys’ club then. In 2007 Hartley was asked to be the chaplain at the installation of the new Bishop of Oxford. One of her jobs was to find somewhere to put his crozier – the hooked stick that resembles a shepherd’s crook – while he was preaching.

‘I had to wander around the back and prop it up. I remember walking past a bishop who does not support the ordination of women. He looked at me holding this crozier and he said, “Hmmm, suits you!” And at that stage there were lots of conversations about “Are women ever going to be bishops one day?” And here I was carrying this bit of kit. And I remember feeling, “Oh, what?” Because it was the tone of voice and the way it was said – you sort of think, “Oh, that’s a bit…” After the service he made a beeline for me and apologised.’

Hartley is confident sexism does not hold a place in the modern Church, even though there are parishes in her own diocese that don’t recognise her as a bishop. ‘The Church of England,’ she tells me, ‘is a broad church where a lot of people can find a home.’ But some Anglican parishes are ‘exempted’ from allowing women priests. Isn’t that a problem?

‘Look’, she replies, ‘if I really got worked up about it, I would be consumed by negative thoughts all the time. I choose to be realistic, I choose to be hopeful and I choose to hopefully set an example. I have met some male colleagues who have changed their mind about the ordination of women because of meeting me and seeing me.’

What many people will see today as she leads the Easter service in Newcastle Cathedral is a devout woman unafraid to speak her mind, who shares her life with her musician husband Myles, whom she met as a postgraduate student in Oxford in the late 1990s. Other members of the diocese will catch sight of her running 10k races or jogging in Gosforth. She says it clears her mind.

One thing that might have made her different is the fact that she hasn’t spent her whole working life in the hierarchical and male-dominated confines of the Church of England. In 2014 she and Myles moved to New Zealand where she took up a teaching post in a theological college. The New Zealand Anglicans were already appointing women bishops and, when the diocese of Waikato – including many of Maori descent – pressed Hartley to go for the job, she got it. Hartley spent three happy years in the post before what the Maoris call ‘turangawaewae’ – the call of home – pulled her back to England. ‘I learned a lot about myself and my faith through it,’ she says, adding, ‘Among the bishops, there needs to be transformation.’

How does she think that might happen?

‘It might be helpful for some of my colleagues to spend time in a part of the communion where there is no established dynamic.’ By which she means taking some time out from ‘the club’, stepping out of the hierarchy.

By now my taxi back to the station has arrived. And on the way to meet it I’m thinking – even though it probably won’t happen – the first female Archbishop of Canterbury? Suits her. Because whatever else she may be, the woman ushering me out of her palace is no coward.

TIMELINE OF A CHURCH OF ENGLAND SCANDAL

1970 John Smyth starts volunteering at UK evangelical Christian holiday camps for children from UK public schools. Justin Welby first attends in 1975.

1977 A boy at one of the summer camps is physically abused by Smyth. He later describes how he was beaten with a plimsoll after stealing a chocolate bar from a shop.

1978 Staying with Rev Mark Ruston, Welby is heard having a ‘grave’ conversation about Smyth. Smyth indicates a boy should self-harm due to his sexuality, leading the victim to attempt to take his own life.

1981 A victim recalls Smyth using a flag in the garden of his Winchester home to denote abuse taking place in the shed. If the flag was up, nobody was to approach. A church chaplain warns Welby: ‘One of the boys had a chat with me,’ advising Welby to steer clear.

1982 A victim attempts suicide rather than face another beating. Rev Mark Ruston compiles a catalogue of abuse. He sends it to seven recipients, not including Welby.

1984 Smyth moves to Zimbabwe and then South Africa in 2001, abusing at least 85 boys in Africa.

2013 Victims come forward to the Church. Welby is informed in August, months into his role as Archbishop of Canterbury. He has an opportunity to report Smyth but fails to do so.

2017 A Channel 4 News investigation, in which Smyth is tracked down by reporter Cathy Newman, makes the allegations public. Hampshire Police start making their own enquiries.

2018 Smyth, now wanted by British police for questioning, dies before he can face justice.

2021 Welby meets survivors four years after the Channel 4 investigation first airs.

2024 On 7 November the Makin Review states that Smyth’s ‘abhorrent’ abuse of 100-plus children and young men was covered up by the C of E for years. On 12 November Welby resigns.