The Origins and History of the Order of Free Gardeners

by Robert L.D. Cooper

(Eaton Socon, St Neots: Lewis Masonic, 2024)

ISBN: 978 0 85318 656 4 (hardback)

152 pp., 17 col. & b&w illus.

£27.00

One of the curious aspects of scholarly investigations in these islands is a palpable reluctance to investigate topics such as Freemasonry: the subject is studiously avoided by many, most supposedly dispassionate historians whinnying with fright at the mere mention of it. Serious scholars, uninterested in the usual conspiracy-theories or the universal sport of bashing the Craft, have long realised that Freemasonry is of major importance, especially in considerations of the 18th-century European Enlightenment, and, in the face of deep suspicion and palpable resentments, have managed to publish thoroughly researched papers and books on a topic that has scared off prissy and pusillanimous “researchers” content never to venture beyond well-tilled fields.

Some years ago, when, having had the temerity to investigate fields unploughed by others, I was subjected to ridicule, disbelief, and hatred for daring to write about subjects which others had either ignored or failed to recognise as important and neglected areas for research, I was gratified when one perceptive critic hazarded the opinion that the “fury against me … was an implicit admission” that I was right. I was comforted to a certain extent by the fact that Freemasonry had been viciously attacked by several Popes, sundry Ayatollahs, Italian Fascists, Spanish Falangists, the Inquisition, Vichy France, the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, Soviet Communism, ill-informed and bucranially ignorant British journalists, and the more ludicrous sections of England’s Loony Left: with such enemies, I reflected, there must be something of value in the Craft. Pope Clement XII (r.1730-40), who was noted for his political naïvety, attacked Freemasonry’s natural bias, secret oaths, religious attitudes, and much else in the Constitution In eminenti (28 April 1738), a Bulla of the Mandamenta class, that is an Act of Condemnation: what the Papacy found particularly worrying was Freemasonry’s indifferentism, which to Masons was actually Tolerance.

Widespread ignorance, absurd perceptions, baseless suspicions, malicious rumours, and sloppy reporting in heavily biased media are unhelpful, especially when one of the most significant threads running through the Enlightenment was provided by the Craft. Take the work of Mozart, for example, the great musician who made the 18th century sing for ever in our ears: not only did he write many works specifically for Masonic ceremonies (the Maurerische Trauermusik [Masonic Funeral Music, KV 477 or 479a] of 1785, for example, is a case in point, an extremely condensed and powerful work, stuffed full of all sorts of allusions, though those would escape the deaf and deadened sensibilities of most today), but much of his later output would also be unthinkable without Freemasonry, which seems to have satisfied the composer’s innermost self far beyond what conventional religion could ever provide.

Robert L.D. Cooper, who held the position of Curator of the Grand Lodge of Antient Free and Accepted Masons of Scotland for many years, has wielded the sword of truth in demolishing and debunking the uninformed scribblings of fantasists dabbling in the supposed “histories” of the Knights Templar, the Craft of Freemasonry, the St Clair Family, and, most significant of all, his splendid demolition-job on the ridiculous effusions and tiresome babblings that have done so much to create widespread misunderstandings of, and dangers to, Rosslyn Chapel, situated north-east of Penicuik in West Lothian, Scotland. This extraordinary late-mediæval ecclesiastical building is actually the only completed part (the choir and east end) of what was to be a large, cruciform collegiate church, the main interest of which is the superabundance of very fine late-mediæval vigorous and inventive sculptural decorations and embellishments, astonishing survivals given the iconoclastic savagery to which most pre-Reformation buildings in Scotland were subjected in the 16th and 17th centuries. This building, therefore, was all about the welfare of souls in the hereafter, an overpoweringly deep concern of the later Middle Ages, requiring constant intercessions from the living, and therefore vast expenditure (called chantries) on buildings, chapels, clergy, monuments, and tombs. Such earthly interventions were expressly condemned by the Reformed religions, and even Purgatory was regarded as a “vain opinion” by the English Parliament, so the whole apparatus connected with the fate of souls after death fell into disuse where Roman Catholicism was no longer the dominant faith.

And that brings me to a consideration of why Scotland appears to have been so important regarding the evolution of what is known as “speculative Freemasonry”. It would seem that Masonic organisation and ritual evolved as responses to stern Reformation principles, and appear to have been attempts to fill the void caused by the abolition of colour and ceremony by a somewhat dour Calvinistic Church, and were brought south by the Stuart Court from 1603. Fraternities in Scotland arose from the working lives of those who created them, and were intimately connected with the practical skills of craftsmen and working people. Those Scots “societies”, “fraternities”, or “orders” included the Free Wrights (carpenters), Colliers (an overtly political organisation, associated with the coalfields), Fishermen, Gardeners, Hammermen (those who worked with metal, including blacksmiths, etc.), Horsemen, and Masons. It is interesting that, quite early in its history, Freemasonry admitted men to its Lodges who were not stonemasons, and this tendency became pronounced in the 18th century as the Craft spread worldwide.

As Cooper points out, the interesting little town of Haddington, in East Lothian, a Royal Burgh so created as early as the time of King David I (r. as Earl of Cumbria over southern Scotland from 1107, and as King of Scots, 1124-53), possessed all the usual crafts and trades, nine of which obtained incorporation status. These were the Baxters (bakers), Wrights, Masons, Hammermen, Cordiners (shoemakers), Tailors, Wobsters (weavers), and Fleshers (butchers): the Baxters received official recognition in 1550. The Gardeners, however, never received incorporation status because most members worked and lived outside, so their calling could not be considered as a Burgh Trade, but from the Gardeners’ Interjunctions of 1676 it would seem that they may have taken leaves from the Masons’ example, for the latter had an additional level of organisation quite separate from that of Incorporation, namely the Lodge.

Lodges of “Ancient Free Gardeners” were known to exist in Arbroath, Falkirk, Haddington, Linlithgow, and many other places, and appear to have been in contact with Lodges in Germany, importing seeds and roots and distributing them among their members at prime cost. Lodge members co-operated with and guided those who were admitted to the Lodges, educating them in the skills of gardening and instructing them in matters of probity and behaviour.

Although Cooper firmly states that “Free Gardenery should not be considered in any way Masonic”, and should “never be included in the ‘family’ of Masonic orders”, there are striking parallels in terms of symbols and regalia. The Compasses or Dividers, for example, an architectural and masonic implement, is associated with Virtue, the measure of Life and Conduct, the additional Light to instruct in Duty and keep Passions within bounds. Its association with the Pyramid and the rays of the Sun is also a potent element, and this essential tool of the architect and stonemason is also found connected with the Gardeners. Similarly, the Square, an angle of 90 degrees, enables great exactness to be achieved in building, and, indeed, in the layout of gardens. It is also a symbol of moral probity, and is one of the three Great Lights of Freemasonry. Masons meet “on the square”, with a moral meaning (to act honourably) enhanced by the chequer-board patterns of Lodge floors. To those two important and meaningful symbols the Gardeners added the pruning-knife.

The very iconography and symbolisms associated with Freemasonry are far too complex to be even outlined in a short review: however, the Temple of Solomon, the perfect building which was erected by the Wisdom of Solomon, the Strength of King Hiram’s wealth and power, and adorned by the Beauty of Hiram the Builder’s workmanship, supposedly under Divine Guidance, was and is of fundamental significance to the Craft. It was destroyed by the Babylonians, but after the Jews were liberated they built a second Temple under Zerubbabel, and descriptions of this have played a hugely important part in the iconography of the Temple and the Lodge. According to some authorities, this Temple was in fact a restoration of the Solomonic Temple, which had not been completely destroyed. Huge works of beautification and even Hellenisation occurred under Herod the Great (r. c.37-4 BC), work beginning in 19 BC, continuing until AD 63, keeping the original dimensions of the plan, but enlarging the courts by extending the already vast platform of the Temple Mount. For an understanding of this last and greatest of the Jewish Temples we are indebted to the words of Flavius Josephus (AD 37-c.98) and to the Talmud (actually the Rabbinical texts known as the Mishnah).

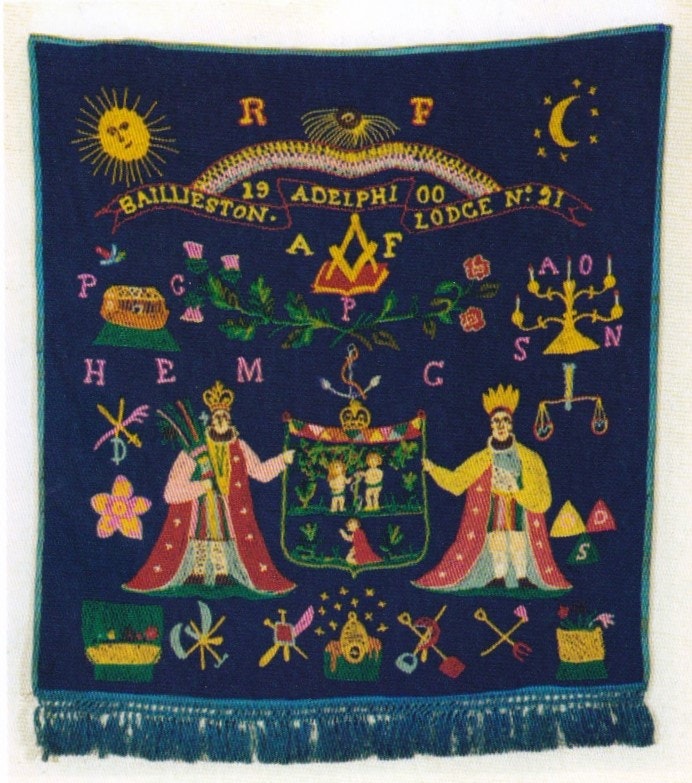

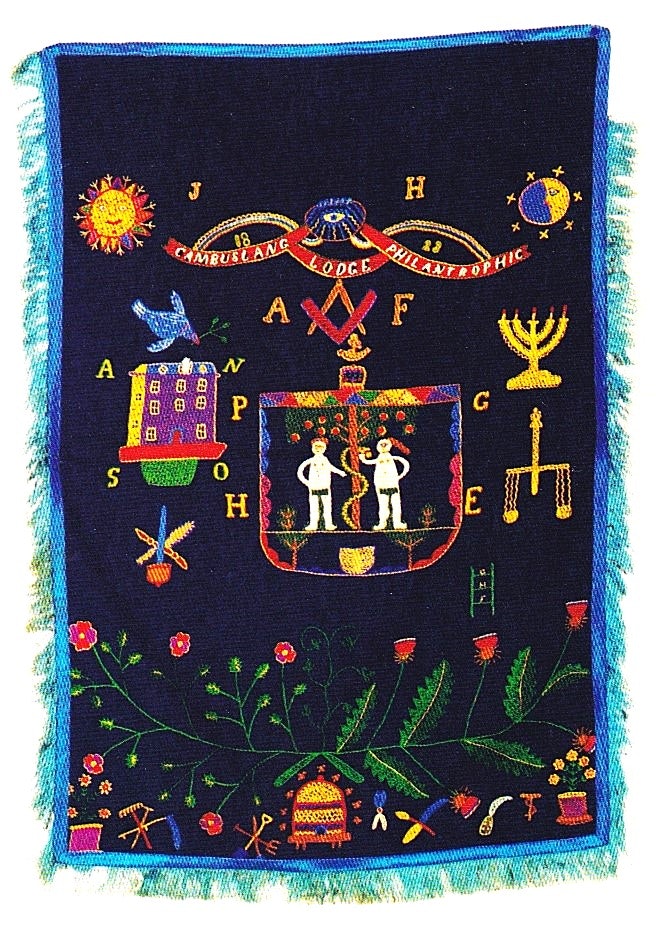

It was therefore inevitable that the Gardeners would turn to the Old Testament for their Lost Exemplar as well, and they ventured even further back, to the Garden of Eden, so their iconography often includes Adam and Eve in the Garden with the Tree and the Serpent. Other signs that occur on the aprons worn by the Free Gardeners include the letters P, G, H, and E, so to the rivers Pison, Gihon, Hiddekel (or Tigris), and Euphrates, all flowing out of the Garden of Eden, and the capital letters A, N, and S can also be found, standing for Adam, Noah, and Solomon. Aprons sometimes are embellished with bucolic representations of Noah’s Ark; a dove with olive-branch in its beak; the sun and the moon; tools used by gardeners (spades, axes, forks, hoes, pruning-knives, and shovels); the All-Seeing Eye; and beehives. Plants associated with Virtues are often represented: the Rose of Sharon and the Lily of the Valley (unassuming Beauty), Hyssop (Modesty), and Cedars of Lebanon (Stateliness and Majesty); while the sins Adam brought into the world are suggested by the Poppy, Hemlock, Deadly Nightshade, Briars, Thorns, and Weeds of all kinds.

In Scotland during the latter part of the 17th century, formal gardens of the nobility began to be copied by lesser nobility and landed gentry, so it is unsurprising that the beginnings of the Fraternity of Free Gardeners coincide with the interest in and application of Renaissance architectural and gardening geometries and themes to the layouts of the landscapes around country mansions, influenced in part, perhaps, by the work of John Reid (1655-1723) in his The Scots Gard’ner of 1683. As I have pointed out elsewhere, some of the most astonishing artefacts in the form of highly elaborate sundials grace Scots gardens: this is all the more strange in a land not noted for its clear skies, and suggest that such objects were intended to point to knowledge of higher learning and esoteric matters far beyond the merely ‘functional’ need to tell the time. Indeed, the compound of architect/mathematician, astronomer/diallist derives from Vitruvian/Renaissance ideals and the notion of the Geometer as the Guardian of complex Truths, Knowledge, Sciences, and Mysteries, which explains why those who were not stonemasons or gardeners (even the nobility) might wish to join the Fraternities in order to gain Enlightenment and become “non-operative” Brethren.

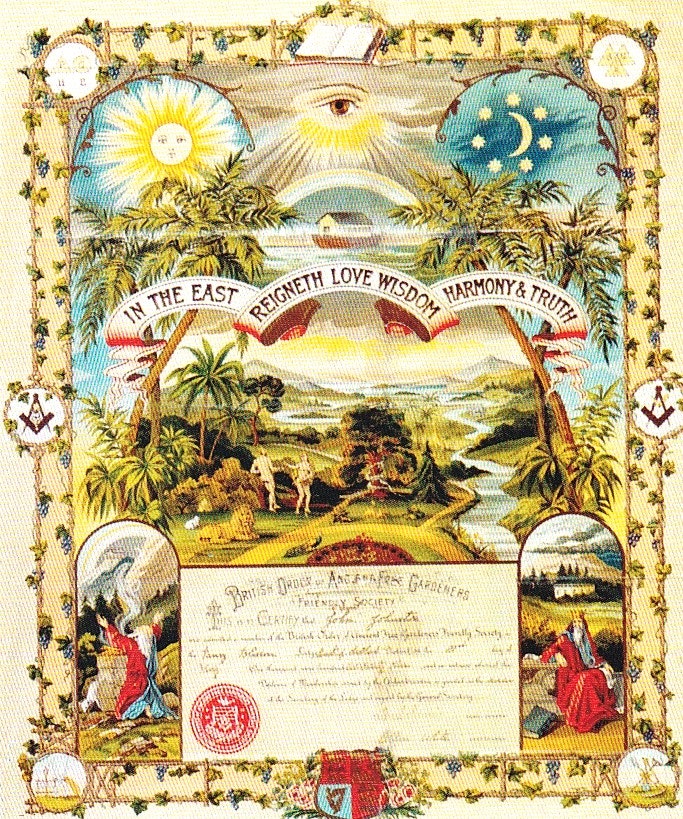

Cooper explains much in this erudite little book, going into “Grips”, “Signs”, “Rituals”, and other matters not unfamiliar from studies of Freemasonry, but too complicated to be gone into here. He provides some tantalising images, such as a certificate of the British Order of Free Gardeners dated as late as 1947, with a panoramic view of the Garden of Eden (complete with Rivers, Adam, Eve, the Tree, and the Serpent) in the centre, Noah’s Ark safely afloat, the Sun, All-Seeing Eye, and Moon, and much else.

In many instances the Free Gardeners declined in influence and numbers, many ending up as Friendly Societies until finally wound up, largely because of the problems of associating Lodges with such Friendly Societies, all of which Cooper explains. Even in Haddington, where the Fraternity had been quite a force at one time, with its own Lodge situated in the Gardeners’ Arms, the pub ceased to be a pub some time ago, and the whole historic area has been threatened with redevelopment. The Gardeners’ symbols were prominently displayed on the front of the building.

This is an introductory book on a subject that deserves to be better known, but what on earth possessed the publishers to bring it out with no index at all, thus severely reducing its usefulness? There are endnotes to each chapter which are nuisance: they would have been far better as footnotes, where the reader could consult them without having to rifle through the pages for information to read. Publishers seem to be averse to footnotes, preferring to inconvenience and annoy readers by making their books a pain to access: they seem to be under the delusion that footnotes suggest inaccessibility and something too “academic”. A bit more common sense, proper placing of notes where they are both readable and useful, and provision of a good index would help many a book published today, not least the one under review.

It is to be hoped that Robert Cooper will be able to expand his research into a much larger volume, far more profusely illustrated (with long explanatory captions under each picture, because the captions under the few illustrations in this book are less than informative). One would hope that it would include an illustrated glossary of terms, symbols, and signs; a really full bibliography; and a proper, comprehensive, all-embracing professionally compiled index.