This article is taken from the March 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

In a trendy art gallery in Potsdam, on the green edge of Berlin [1], a gaggle of German journalists have gathered for the opening of an extraordinary exhibition. At first glance, In Dialogue looks like a refreshingly conventional display of figurative painting: portraits, landscapes, citysca pes … Yet when you look a little closer, you realise there’s something odd about it — something strangely disconcerting, like the vague memory of a bad dream. And then you read the captions, and you realise what’s amiss: these pictures were all painted under the watchful eye of one of the most repressive dictatorships of the Soviet era, the German Democratic Republic [2].

In 1990, after the GDR was absorbed into the West German Bundesrepublik, East German art was left in an awkward limbo. From the foundation of the GDR in 1949 to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the only art on public show was art sanctioned by the regime. As the crimes of the GDR came to light (hundreds killed fleeing to the West, thousands persecuted by the Stasi), German curators were understandably reluctant to celebrate artworks which had been used to promote this tainted socialist state.

When I first travelled to Eastern Germany in the early 1990s, I found East German artworks locked up in the basements of museums. East German curators were embarrassed by them; West German curators didn’t know what to do with them. Like virtually all state institutions, the GDR’s major galleries had been controlled by hardline communists. The West Germans who had replaced them meant well, but they knew little about East German art.

In spite of all the state restrictions — their diverse and enigmatic paintings are much more potent than West German artworks

East Germans had had their fill of socialist realism during the Cold War — that was the consensus. For 40 years, they’d been bombarded with propagandistic pictures of happy, heroic proles. Now at last they were free to see the avant-garde Western artworks they’d been deprived of — the Pop Artists, the Abstract Expressionists … Meanwhile, East German art was hidden away.

As reunification receded into history, this 40-year chasm in East German art collections became increasingly conspicuous, and lately big public museums, such as the Museum der bildenden Künste in Leipzig, have been filling that gap, showing that not every artist in East Germany was a Communist Party shill.

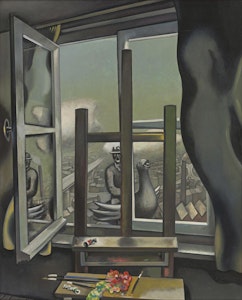

The communist regime may have favoured banal daubs of muscular, messianic manual workers, but many East German artists were a lot more nuanced. Only rarely were they overtly critical, but their oblique critiques were much more powerful than agitprop. Rather than confronting the regime head-on, their subtle pictures evoked the torpor of this paranoid one-party state.

One man has been a key architect of this important reappraisal — billionaire businessman Hasso Plattner. Born in Berlin in 1944 and raised in Bavaria, Plattner made his fortune in software, but he’s equally renowned in Germany as a champion of East German art. In 2017, Plattner opened the Barberini Museum in Potsdam, a beautiful Italianate building — brand new but built in baroque style, in harmony and sympathy with the historic buildings that surround it. The Barberini’s opening show, Behind the Mask, drawn from Plattner’s own collection, was a fascinating display of East German art which confounded our simplistic western preconceptions.

I came away from that groundbreaking show with a fresh appreciation of this maligned, neglected genre — eager to see more of these artists, who’d been shut off from the West for 40 years. It seems I was not alone. Thanks to pioneers like Plattner, the East German art revival gathered pace. In 2019, at the Kunstpalast in Düsseldorf, one of (West) Germany’s leading galleries, I attended the opening of Utopie und Untergang, a lavish retrospective of East German art, opened by German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier. Was this conclusive proof that East German art had finally come in from the cold?

Not quite. Nowadays, East German art is a lot easier to find in German museums than it used to be, but it’s still only a marginal presence in most German galleries, overshadowed by West German artists of the period such as Joseph Beuys. That’s what makes this new show, at this new gallery, so timely and influential. Half a lifetime since reunification, Germany is still split between East and West, politically and economically. With more and more East German voters shunning West German parties, Germany can no longer afford to ignore the culture of this controversial, contested epoch. Plattner’s sleek museum provides the forum that this overlooked art requires.

Das Minsk was built by the East German regime in the 1970s, in that stark modernist style beloved by communists the world over, to house a cultural centre devoted to the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (Belarus). Stylishly restored by Plattner’s foundation, it reopened in 2022. A short walk from the Barberini, it houses his huge collection of East German art.

In Dialogue features dozens of arresting paintings from the Hasso Plattner Collection, but this insightful, intriguing exhibition, curated by British expat Daniel Milnes, is more than an assemblage of greatest hits. Its starting point is a book by East German art critic Henry Schumann, published in 1976, in which he interviewed 20 artists living and working in East Germany. In the West, such a tome would be no big deal — indeed, our bookshops are overrun with them — but in a regime which exerted fierce control over what its citizens wrote and said (and thought), this book became a cultural landmark.

Yet what these East German painters painted is much more interesting than what they said. For, in spite of all the state restrictions — or maybe, in some way, because of them — their diverse and enigmatic paintings are much more potent than most West German artworks of the same period. How come?

In West Germany, artists aped America: minimalism, conceptualism, all the latest fads and fashions … Painting was seen as old hat, an archaic antiquated art form. Artists were free spirits. They could say anything, do anything. They could let it all hang out. In East Germany, conversely, state-sponsored artists aped the social realists of the USSR, and their paintings were dull and dreary.

What In Dialogue reveals is that there was also an East German underground, artists operating under state restrictions but still pursuing their own agenda. It was in this artistic no-man’s land that creativity thrived. It’s an illustration of that old adage: the pearl is the disease of the oyster.

For artists, living in the GDR was no fun at all, but while West German artists produced flashy iconoclastic artworks whose appeal was brash and fleeting, East German artists toiled away at their easels, in poverty and isolation, painting discreet and complex pictures whose appeal will endure and prosper, long after the tyranny which tormented them has been forgotten.