It is the most unoperatic of operas: an austere two-and-a-bit unbroken hours of (for the most part) gloom-laden low voices and an exceptionally laconic orchestra, equally subfusc, often thinned to a single line accompanying the not outrageously tuneful soliloquies of one character or another ― who, this being a Russian historical drama, generally seem to be furiously competing in the World Lying Championships.

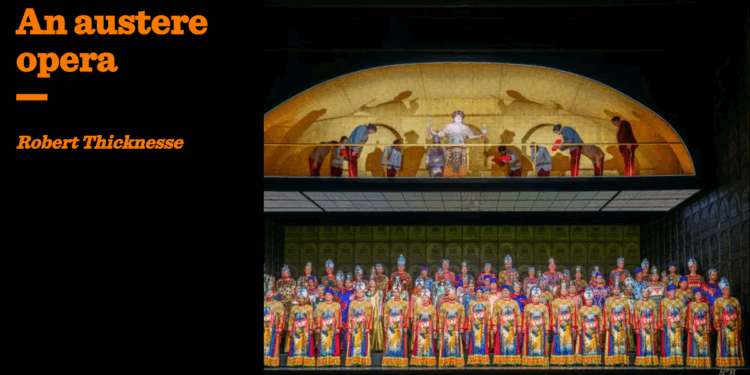

And yet it’s pretty compelling, even in this intense but somehow over-controlled and not very exploratory staging by Richard Jones, seen first in 2016. Yes, there are outbursts of massive choral and orchestral colour and pageantry, and a pliant, suffering populace alternates between neighbourly gossip and placidly waiting for the next dreadful thing to happen, but not a lot of showbiz to distract from Mussorgsky’s extremely terse seven-scene drama of 1869, reduced from a 24-scene play by Pushkin that draws heavily on Macbeth and Richard III.

Until quite recently, everyone performed the expanded and much more spangly version that Mussorgsky wrote when this original was rejected by the Mariinsky Theatre — and then usually in the gussied-up version by Rimsky-Korsakov, who laboured mightily to make his dead friend’s bracingly original, spare, skeletal music into something acceptable to bourgeois taste. That’s the version we all grew up with, until the formerly sainted (now anathematized) conductor Valery Gergiev began to champion this schematic, black-hued version, with its no-way-out momentum and general air of doom.

If that doesn’t sound a wildly attractive prospect, the next issue is the music: fabulous in its starkness, something that conductor Mark Wigglesworth really works on here with a lot of quasi-Expressionist orchestral effects so that sometimes it has the feel of a neurotic Hitchcock score as unearthly string susurrations warp into nightmarish, metallic tremolos. But it’s really hard to make this score work as drama — sometimes it feels like there are more pauses than notes in it, and not many conductors can engineer the required tense, breath-holding angst out of those, until the music speeds up and fills out, and gains a more traditional kind of momentum, as the later scenes accelerate towards Boris’s end.

And so, after the fun of the jangly Coronation with its deafening cacophony of bells, the early scenes are definitely heavy going. Pimen, the old monkish scribe, starts all the trouble with his tendentious history and the teeny nudge he gives his young acolyte Grisha to start getting his act together as the Pretender — impersonating the Tsarevich Dmitri whom Boris reputedly bumped off to get to power — who will bring foreign invasion and a decade of disaster to Russia (so that worked out well…); we get a dull sort of Powerpoint version of history, without much charisma. The boisterous drunken mendicant Varlaam (Alexander Roslavets) gives the scene at the border inn (as Grisha tries to skip out to Lithuania) a bit of energy, but things only begin to perk up in Scene Five when at last we get to see Boris, in human form, with his children ― a touching scene, finally with some high voices and violins unleashed from their bottom string, struggling out of wormy turmoil into the stately and lovely tunes that Mussorgsky saves up for these moments.

And here, back again, is Bryn Terfel, who has sung every performance of this staging. The voice isn’t as full as it was, but Bryn gives us a lot more sighing and groaning to pad out the expression, and is affecting and sympathetic as this man crushed by guilt for his terrible mistake, and the bad times that have suddenly descended on Russia (bad weather, famine). It’s valedictory from the start, even the nearest thing he has to an aria, a very Shakespearean soliloquy straight from Pushkin, where he bitterly understands the vacuity of power. The snaky boyar Shuisky feeds Boris paranoia-inducing stories of the Pretender, and in the opera’s most famous scene the raving Boris is traumatised by visions of the dead child … this is all very effective, but one does long a bit for the horror-histrionics of a Chaliapin, rather than Terfel’s — or I suppose Jones’s, really — interiorized torment.

Now things are moving, with Boris berated by the crowd outside the Kremlin and denied comfort even by the annoying Holy Idiot, who wails the theme-tune of Russian history: “Night is falling, the enemy comes…”. The orchestra roils away with anguished energy. Back indoors, Pimen (Adam Palka) delivers the final straw, (fake?) news that the slain child’s tomb has started working miracles. Boris dies, brokenly but nobly as the orchestra subsides from its alarming outbursts and terrifying, swooping tremolos back to thread-like texture for the hopeless end.

There are a lot of strong voices: all those saturnine basses, and Jamez McCorkle’s forthright Grisha, that reinforce the inexorable feeling of the work. But frankly this all feels more like a ritual than a drama, and lacks the resonance to break out of its locale into something universal. We don’t all have to be mavens of Russian history by any means but Boris, with Mussorgsky’s later Khovanschina, is very central to the matter, being written in a tiny window of opportunity under Alexander II when history was suddenly not the wholly-owned property of state security, and, channelling the older texts of Nikolay Karamzin, and Pushkin’s Shakespeare-filtered retelling, is a useful glimpse into the paranoid, exceptionalist heart of Russian self-conception ― more a state of mind than an opera, perhaps.

As it happens, there was a staging of this version ― at ENO years ago, by Tim Albery, magically conducted by Ed Gardner ― that really nailed its musical and dramatic power, revealed it as the grim commentary on the human condition that it can be. Here neither the crowd nor Boris himself really grab the heart of the drama, so we’re caught between stools. And surely it’s about time we got the full-fat version again, with its devilish anti-hero Cardinal Rangoni, machinating the Polish princess Marina Mniszech into teaming up with Grisha for a no-shit invasion of Russia, the Idiot finally returning to the blasted wasteland to sing his miserable song again, and the bloody mayhem Boris kept at bay for a bit ― in the Russian view, as good as it gets ― poised to descend yet again.