This article is taken from the February 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Half a century ago, at a conference of Asia and Pacific TV news chiefs in Hong Kong, I was deputed as the youngest delegate to escort Australian and Japanese execs around the girlie bars. Exhausted, I retired early the second night and turned on the telly in my room. There were two channels, English and Chinese.

A third, Beijing, could be glimpsed if the aerial was hung out of the window.

I saw an orchestra on the screen.

A conductor came on and gave the opening beat for Beethoven’s fifth symphony. The stentorian notes crackled through. I couldn’t believe my eyes. Grabbing a coat, I ran down to the bar, shouting, “Guys, the Cultural Revolution is over!”

Bleary heads glared at me over flat beers. “No one plays Beethoven to change policy,” growled one veteran. I pointed to the day’s date: March 26, 1977, the 150th anniversary of Beethoven’s death. Typical of the Chinese to issue a symbol instead of a statement.

Weeks passed before the media recognised that China was using an orchestra as an allegory of its new direction. Over the previous decade, Mao’s Red Guards had broken musicians’ fingers and sent the victims for “re-education” in paddy fields.

Many died. Some who played in the Beijing Beethoven broadcast had (I later heard) not held an instrument in years. Yet when the Mao gang wanted to signal change, only a symphony orchestra would do. Why an orchestra?

Fast forward four decades. I am at a conference of Asia and Pacific orchestras in Shanghai. A speaker from China says they are planning a hundred orchestras. Fifty million children are taking piano lessons. The best are given Party scholarships to study in elite American schools. Lang Lang and Yuja Wang are brand leaders. China will dominate music within a generation.

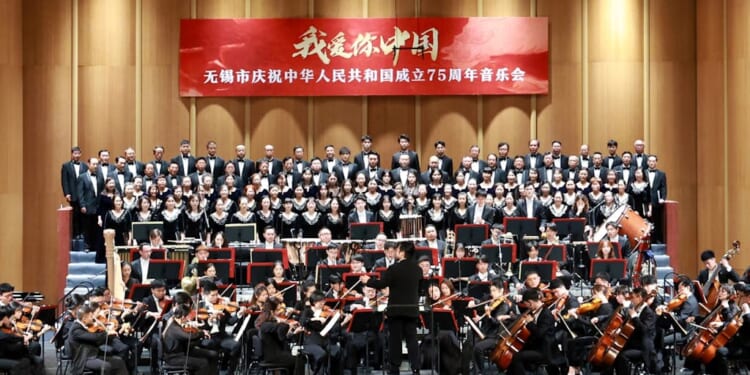

The number of orchestras there doubled from 48 to over 90 in the years 2008 to 2022. My Chinese friends confirmed this month that 80 to100 orchestras are presently registered with the relevant ministry. The latest are Wuxi City Orchestra and Huaihua City Orchestra (2025). Across China there are at least 100 more training orchestras.

Beneath these astonishing reversals — from suppression to state support, zero orchestras to hundreds — there is a canny consistency. China grasped that an orchestra is more than a payroll of musicians playing timeworn masterpieces. An orchestra is an organism that defines a city or a country, more imposing than skyscrapers or Olympic medals. It is a token of a society’s ability to cooperate in the pursuit of cultural excellence.

Its independent existence goes back less than two centuries. In the 1840s, “societies of friends” in Vienna and New York sponsored workless or disgruntled musicians to give symphony concerts. In Vienna, opera-house rebels banded together as the Philharmonic.

In New York, hungry immigrants presented the American premiere of Beethoven’s ninth symphony. Berlin and Boston caught up in the 1880s. London did not acquire an orchestra until the 1900s.

The Vienna Philharmonic became the city’s ambassador, waltzing in the New Year for 150 screen-bound nations. The Philharmonic today defines Vienna in the public mind, more than all the schnitzels, strudels, Gustav Klimts and Eurovision finals.

New York faced a challenge from Philadelphia, where Leopold Stokowski patented a sound that appealed to the nascent film industry. The NY Phil hit back with media personalities from Toscanini to Bernstein (and latterly Dudamel) whilst raiding Wall Street for a quarter-billion dollar endowment fund. Nothing says New York more than its Philharmonic orchestra.

Joseph Goebbels got the message. The Nazi propaganda minister recast a faltering Berlin Philharmonic as the Reichsorchester, a model of cultural supremacy covering for racial mass murder. Later, in the Cold War, Herbert von Karajan recast the Berlin Philharmonic as a miracle of economic regeneration — Vorsprung durch Technik. The focus changed, not the function.

In London, four orchestras refused to be welded into one flagship, each clinging to esoteric distinctions. Their focal myopia, allied to the maladministration of two concert halls, has led to a crash in the profile of symphony concerts. Until around 2000, London was an orchestral destination. These days, the Berliners and Viennese hardly bother to visit.

We have seen cities rise or fall on an orchestra’s image. Birmingham, in the 1980s, was a pus-filled scar of industrial failure. Two Liverpool lads in their twenties, Simon Rattle and Edward Smith, restored its pride with an orchestra and a symphony hall that are the envy of their nation.

In the great American rustbelt, cities like Cleveland and Detroit maintain a purposeful identity through their orchestras. Beneath the Hollywood Hills, the Los Angeles Philharmonic in Frank Gehry’s Walt Disney Hall add a gloss of civility. Imagine LA without orchestra or hall. The city would have less character than Seattle.

Which is why, compressed into TikTok clips, societies are still founding and funding orchestras. The United Arab Emirates is the latest, opening this month. Qatar already has a Philharmonic. Saudi Arabia may be next.

Is that a trophy acquisition, the new Rolls-Royce or Rolex? Hardly. Whilst oil-rich nations can afford a veritable warehouse of so-called Veblen luxuries, where demand increases as the price rises, an orchestra represents a higher pitch of virtue signalling.

It sends a message that a society, confident in itself, wishes to be associated with the most sophisticated form of music production, involving a hundred highly trained experts who work together in pursuit of an ultimate refinement.

As the Chinese know, an orchestra is, in some subliminal sense, a model of human collaboration and coexistence. Have we learned that lesson?