Who wouldn’t love to be a moderate? What is the world without tending one’s garden, small incremental changes, and calm, serious observations?

However, in the last 10 years this Arcadian dream has become impossible for the Western right. Crashing against consensus, banished online, Britain’s and America’s conservatives have been swept into a revolutionary temper.

Exciting, crass, and vulgar, this may be a recipe for electoral success, but unless the right’s vanguard can keep it under control, they will succumb to their own anarchic tendency. Remember the economy, but please don’t be stupid.

The populist right has shown it can win on energy and progressive missteps alone. The 2024 US election is proof enough of that. Yet when it comes to government the case is far from certain. The Greenland debacle of the last few weeks has shown a movement with no principles beyond the whims of the day. This shouldn’t even be a problem as long as it kept the principle of trying to maximise its electoral success. Alas, even that is a bridge too far.

Two great spirits threaten Britain’s Reform revolutionaries: the stupid and the scary

Coupled with an online streaming sphere which seems to be asking to be censored — partly because it is— the new right can’t escape the edginess it was born into. This combined with concerning polling numbers creates a feeling that Trumpism and its side effects are a medicine Americans won’t want another dose of. In Britain, despite Reform’s dominance in the polls, it has reason to fear the same.

Two great spirits threaten Britain’s Reform revolutionaries: the stupid and the scary. The latter are easy to distinguish, being actual ethno-nationalists, antisemites, or something beyond even that. The far more common, and hence more dangerous, variant is the stupid, as events across the Atlantic have made clear. Niche issues from one online community suddenly become occasions to burn as much political capital as possible for effectively no political gain. A natural distrustfulness of authority makes government action anathema to its own supporters.

In the New York Times, conservative pundit Ross Douthat called for a stable nationalism removed from the “demagogic” to-ing and fro-ing of the president. The problem is that removing nationalism from the enthusiasm which fuels it seems impossible. Social media acts like the great crowds of the French Revolution, with farcical and fearsome groups emerging from their apocalyptic fringes. Revolutionary governance was impossible because the crowd controlled the course of events, not any executive of the period.

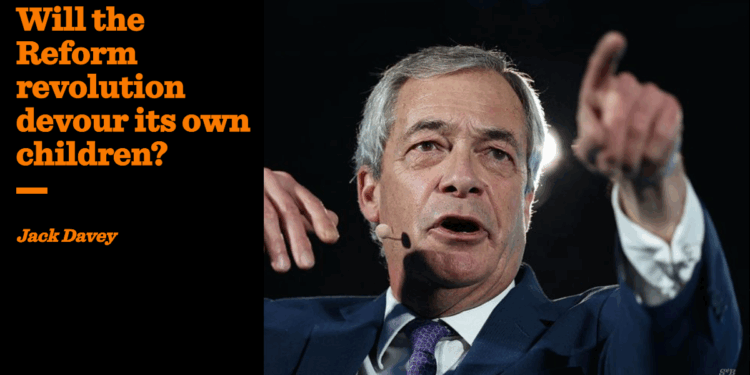

Here Nigel Farage could learn from Robespierre. While part of what gives the “New Right” its energy is that it is amorphous and able to tackle the established parties from any and every direction, this very fact lends it to almost immediate chaos and infighting. The revolution many desire can only be achieved by government, not by those outside it. Although Robespierre is defined as the apogee of revolutionary fanaticism, he was the one who crushed the power of Paris’s crowds and the Commune. The answer is not terror but it is definitely order.

To govern effectively, Reform will have to develop a hierarchy and discipline that it is hard to envisage now. Already skittish after the betrayals of 2016 and 2019, any failure will immediately be cried upon as treason by more extreme sections which seek to go further. Keeping MPs on a tight leash is one thing, but the kaleidoscopic whirlwind of the online right presents a different challenge entirely. Rigidly enforcing the boundaries of who MPs and outriders can speak to and agitate for is easier to contemplate when dealing with some scarier factions, but inevitably some of the stupid will seep through.

To make a successful revolution, you have to end it first

None of this will be popular but it will be necessary. While Nigel Farage spends much of his time railing against Keir Starmer’s attacks on freedom through the Online Safety Act or digital IDs, this may not survive contact with government. No radical — never mind revolutionary — government has ever been more pro-freedom than the Ancien Régime it replaced.

Alexis de Tocqueville, who inspired the thought above, saw the revolution of 1848 take place around him. The government had fallen, and he spoke to a worker rushing towards the barricades. He said to him, “Reform forever! You know the Ministry has been dismissed?” “Yes, sir, I know,” replied the worker, jeeringly, and pointing to the Tuileries, “but we want more than that.” One hundred and seventy-eight years later, the lessons from that revolution, which collapsed under its own fanaticism, still hold true. To make a successful revolution, you have to end it first.