The ubiquitous mockery of a botched restoration offered a revealing insight into modern cultural decline

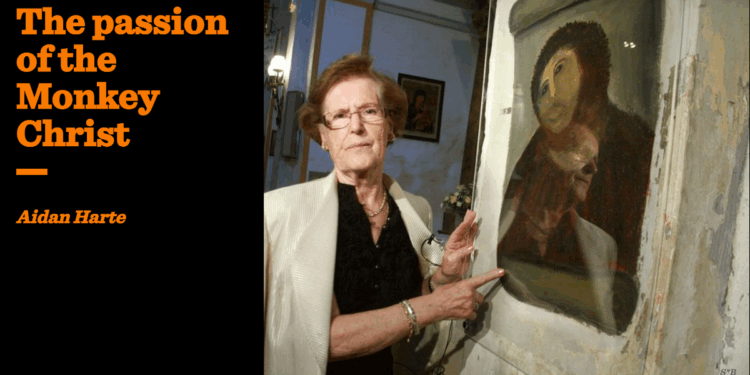

In the last days of 2025, Cecilia Giménez, creator of one of this century’s most famous paintings, died. That her name rings no bells would not have surprised the French literary critic, Roland Barthes.

Barthes is one of those writers whose lifework is distilled in the popular imagination to a single phrase. In 1967, he secured immortality by proclaiming “the Death of the Author”. The last fellow to cause such a stir was Nietzsche announcing God’s demise. No less radically, Barthes argued that creator and creation must not be confused, that a writer’s or painter’s intention is an irrelevant consideration in the evaluation of a work of art. This thesis struck a chord with a generation eager to find new meanings in a dusty literary canon. Others, like Foucault and Derrida went even further, using the author’s dethronement as a wedge to deconstruct politics, language, gender — you name it. Even if Barthe’s idea was essentially destructive, it cannot be lightly dismissed. Like Nietzsche, he was on to something.

And the mysterious Mrs Giménez?

In 2012, her botched restoration of a fresco in a Spanish church became notorious as “Monkey Christ”. That cruel nickname and the haunting image that the octogenarian had inadvertently created inspired mockery across the world. An increasingly atomised society with few shared cultural experiences found itself briefly united in hilarity at the defacement of a key Christian image, Christ’s Passion. Mrs Giménez’s good intentions, or her feelings about the global pile-on, were irrelevant. Her amateurish artistic efforts had produced a perfect meme for the first fully online generation.

But of all the genres, comedy ages worst. Show me one who finds the plays of Aristophanes funny and I’ll show you a liar. Online humour is especially ephemeral and esoteric, delighting in its own obscurity and compelled to repeat a gag until it becomes irritating. Obituarists of the 91-year-old struggled to convey what the world had found quite so amusing about Monkey Christ. “Millions were reduced to tears of laughter,” according to The Guardian. The kindest interpretation is that we were laughing at foolishness. There is a very human joy in seeing a job properly bungled. Who hasn’t passed a happy hour watching videos of people falling down ladders and stairs on YouTube? All of us fail, but Cecilia Giménez failed in a way and on a scale few can imagine. We smile in relief that it was only some faceless Spanish pensioner who was found out — and not us.

That relief blends seamlessly into sadism. A spoof article published by Hyperallergic was typical; the Brooklyn-based art journal claimed, with tongue in cheek, that they had persuaded Mrs Giménez, now rebranded as “The Punk Restorer”, to upgrade a series of better-known works. “Below is her handy work. A new revolutionary movement of art restoration is born. Behold genius.” A second wave of memes were born of defaced masterpieces like the Mona Lisa and The Scream, and artists like Vermeer, Van Gogh and Andy Warhol doing the monkey. Next came posters, tee-shirts, wine labels, toys, a heartwarming movie (Behold the Monkey, 2016) and even an opera.

As a practicing artist with some training, stories where a new painting or sculpture suffers public ridicule generally leave me more bemused than amused. Don’t get me wrong, I scoffed at Mrs Giménez along with the mob. Not to laugh would take a heart of stone. But her work was poor only in the way that most amateur work is poor. It is normal for untrained artists to screw up. The difference is that Mrs Giménez’s infamous painting began as an attempted restoration. The layman can compare what she destroyed with what she created. The gulf is indeed comical but had this grandmother confined herself to the traditional subjects of Sunday painters, bowls of fruit and landscapes with sheep, no one would have noticed or cared about her incompetence.

The difficulties amateur artists must surmount are compounded by living in a time when draftsmanship isn’t taught well. Would-be painters unversed in academic methods are liable to overrate their own skills and underrate the demands of realism. Someone who cannot keep time, sing in key, or play an instrument cannot be called a musician, but anyone today can self-identify as an artist. The hard-won abilities that once earned that title are no longer required. Visit any big contemporary art gallery — Hauser & Wirth, Pace Gallery or David Zwirner — and you’ll find artists just as clueless of Mrs Giménez selling for megabucks. Is that painter knowingly employing a primitive style or is he simply unskilled? Is he a fauvist or did he never learn to mix colours? If you have the right agent, these questions no longer matter. Tracey Emin can’t draw any better than Cecilia Giménez and it hasn’t held her back professionally.

In 2012 that decadent world was very remote from the church of Santuario de Misericordia. Cecilia Giménez’s ambition was modest, if unrealistic: to repair a fresco from the 1930s. The scourged Christ wearing a crown of thorns, a tragic subject depicted by Titian, Caravaggio, Dürer and countless other masters. Ecce homo, its Latin title, comes from John’s Gospel. It means, “Behold the man”. The words are shouted by the Roman governor to a restless crowd in Jerusalem. The version that became Monkey Christ was painted by Elías García Martínez. No masterpiece, it was a workmanlike and unoriginal variation of a painting you can find in churches across the world.

How could Cecilia Giménez have done better? Firstly, she should have studied the materials and palette used by Martínez. To match them she would have to mix carefully, duplicating the hues and tones of the original. This was beyond her. Christ’s pale skin turns mustard. The light gold background goes grey. The mystery is why she fully painted over the original when only the left side was flaking off. The fresco may have been in a worse condition than pre-restoration photos suggest. More likely, she painted herself into a corner and panicked. Having obliterated the original, she had to redraw it.

That’s when all hell broke loose.

Without getting too technical, to render a head thrown back, a draftsman must conceive of the head as a cylinder then turn it in his imagination, keeping the relationship of the features consistent as they are distorted by perspective. This is challenging. It is not something an untrained artist could hope to do. Eyes are orbs covered in flesh sitting in a three-dimensional skull. Mrs Giménez redraws them as almond shapes on a tilted flat plane. It’s a naïve solution to a difficult problem. Most amateurs do likewise. The last macabre element are the unfinished lips, a ghostly smear that recalls the short story, “I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream”.

Restorationists work with a light touch and Mrs Giménez had a heavy hand. Even if she had talent, she lacked experience. Restoration is a field where the best professionals come under scrutiny. After centuries of candle smoke were removed from the Sistine Chapel ceiling through the 1980s, the results enthralled some and appalled others. Andrew Wordsworth in The Independent complained that the ceiling now had, “a curiously washed-out look, with pretty but flavourless colouring — an effect quite unlike that of Michelangelo’s intensely sensual sculpture.”

Other than Banksy’s middlebrow murals, famous paintings aren’t really a thing anymore

Some commentators took Monkey Christ as evidence of a general decline of technical skill. In fact, there are many figurative artists today — Cesar Santos, Molly Judd, Roberto Ferri to name but three — making original work that bears comparison in quality to the best art of the past. We have not forgotten how to paint. Academic realism is simply not culturally central anymore. What has changed is the ratio of working artists who can “do” realism and the taste of modern patrons.

I said Cecilia Giménez had created one of the most famous paintings of the 21st Century, but that is a low bar. Other than Banksy’s middlebrow murals, famous paintings aren’t really a thing anymore. Cultured Parisians in 1865 could intelligently debate the merits of Manet’s Olympia or Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1916 but there’s really nothing to say about Gerhard Richter’s Abstraktes Bild except that it sold for £24.5 million in 2021. Gallerists and auction houses have responded to the Death of the Author by selling artists rather than art, brands rather than paintings. You may know Ai Weiwei is a famous artist and could you recognise any of his work without a label? Be honest. This commodification suits the very limited audience for blue-chip contemporary art. The rest of us cannot laugh at its pretensions as easily as we can at a silly old lady from Spain.

Not everyone disgraced themselves in the initial frenzy. The American Jonathon Keats mounted a spirited defence of Mrs Giménez in Forbes magazine. Urging readers to “set aside our sneering irony,” he claimed that her handywork, “provides rare raw access to human faith at work.” Through it, Keats says, “we gain access to one woman’s vision of her savior, uncompromised by schooling. Her painting documents a live relationship.”

Alas, her painting does no such thing but it was chivalrous of him to pretend otherwise.

It would be obtuse to ignore the fact that the mockery was loudest in a part of the world which had been Christianity’s heartland. Borja was once the northern border of the Umayyad Caliphate. It was retaken in the 12th century in the Reconquista that eventually unified the Iberian peninsula under a militant Christianity. That tide is now reversed. Churches became mosques, the Cross replaced with the Crescent.

In 2012 the New Atheist movement was still on the front foot. As the hall of monkey mirrors grew ever more refracted, it became obvious that, for many, the object of ridicule was not that Mrs Giménez’s reverent gesture had gone horribly wrong. Reverence itself was the joke. In the age of irony, nothing is so cringe as sincerity. Monkey Christ confirmed the suspicions of those, like Richard Dawkins, who already thought practicing Christians were rubes. And quite unintentionally, Cecilia Giménez’s creation — a profane blend of God, man and ape — visualised the old argument between evolutionary science and biblical literalism in a way that delighted secularists.

There is much talk in our age of ideological tumult about the Overton Window — that narrow range of ideas and policies that it’s socially acceptable to publicly discuss. It also applies to what we joke about, what we don’t. Two years before Cecilia Giménez became “a global laughing stock”, Kurt Westergaard wasn’t laughing. An axe-wielding Somali had broken into his house in Denmark screaming, “We will get our revenge!” The intruder had come to hack Mr Westergaard to death for the crime of drawing a cartoon of the prophet Muhammad. Westergaard and his granddaughter survived by sheltering in a panic room built after another plot to kill the cartoonist was foiled in 2012.

It is revealing that a set of blasphemous images could have generated such different reactions in 21st Century Europe, but revealing of what? The enlightened sophistication of the post-Christian Europe perhaps? It would be flattering to think so but, to any culture that values collective honour, secularist glee at Mrs Giménez’s unwitting creation only telegraphed the West’s self-destructive weakness.

To writers, critics and comedians, the message was clear: Christianity is fair game but Islam is no laughing matter

Contemporary European Christianity may be supine but the mad zeal displayed by Westergaard’s enemies is inescapably part of our Abrahamic heritage: “God is not mocked: for whatsoever a man soweth, that shall he also reap.” Strength of a fanatical variety was displayed in the 2015 Charlie Hebdo massacre. To writers, critics and comedians, the message was clear: Christianity is fair game but Islam is no laughing matter. The lesson was learned all too well by Europe’s terrified political class. Their solution to this culture clash is to try to silence it, with the creeping censorship that has darkened Europe’s once rich intellectual life and promises to extinguish it before long.

The joke was never on Cecilia Giménez. It was always on us.