This article is taken from the February 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

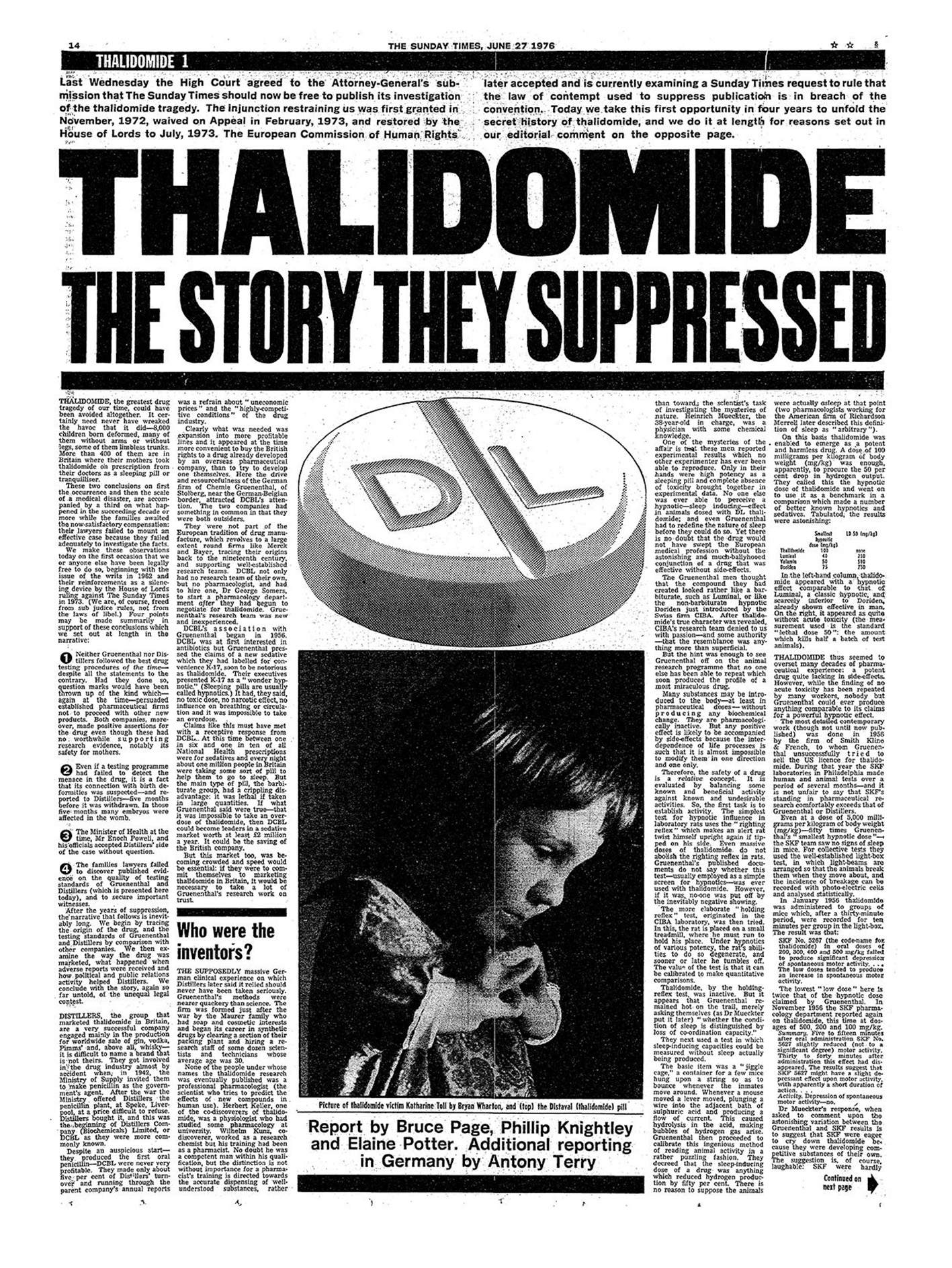

1972 was a remarkable year in the annals of Western journalism. The Sunday Times exposé on the dreadful effects of the drug Thalidomide on unborn babies shocked the medical world and ultimately saved many lives. In the United States, Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein unmasked Richard Nixon in the Watergate scandal, effectively bringing down his presidency. Four years later these two American journalists were portrayed by Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman in the multi-Oscar-winning film All The President’s Men. It was cool to be a journalist, especially an investigative one.

This was a far cry from the days of Bill Deedes and his colleagues as satirised in Evelyn Waugh’s glorious 1938 novel Scoop. Schools of journalism multiplied and youngsters in their thousands sought the fame and success of Woodward and Bernstein. Newspaper circulation was healthy — around 80 per cent of Britons typically read a newspaper daily — as was rivalry between titles. Every editor was looking for the next big story. Few had the impact of the two mentioned above, but there were plenty of worthy exclusives to keep the readers buying in their millions.

Those were the days of the landline and the telex, when local papers thrived and morning editions of London daytime papers were eagerly awaited. Journalists were methodical reporters who, for the most part, gathered information, checked facts and filed their copy. Opinions, on the other hand, were left to leader writers or the occasional columnist. Editors were courted by politicians of all parties and sometimes by industrial leaders. It all seemed to work quite well.

The world is completely changed today. Those newspapers that are left have tiny circulations in print, which are sustained by heavily discounted subscription offers. They rely on online readership to generate revenue and hold their relevance.

They are surrounded, if not engulfed by, an ever-expanding social media where what is referred to as news is very often simply hearsay or malicious gossip peddled by interested parties for the sake of sensationalism. It is a colossal jungle of drivel, which is difficult to navigate without being tainted by the nature of the stories unleashed. The scale of this shift from “legacy media” is astounding. According to Ofcom’s 2025 News Consumption Survey, only a third of Britons now read a newspaper (and mostly online; only a fifth still read a physical newspaper) whilst half the population get their information from social media.

Journalism has suffered from transformation. The sheer speed of information flow that technology has brought has meant that rumours become stories which can evolve into so-called factual reporting within minutes. There is no time for checking the validity if you do not want to be left behind. These days being left behind is perhaps the worst mistake a news outlet can make. There is huge pressure to rush stories to air or into print. This inevitably means the quality and depth of the stories suffer. It is snapshot journalism, yet it just as quickly becomes accepted as truth. No wonder errors creep in with such frequency.

There are other factors at work in declining journalistic standards beyond social media. Cost cutting undoubtedly affects quality. Newspapers and broadcasters are more terrified than ever before of legal action. Litigious celebrities abound and large companies are fast to protect themselves via injunction or legal threat.

I often think of a journalist friend of mine who was fired from his weekly column in a national newspaper well known for its spelling errors after he libelled someone. When asked by his editor if he had checked the story, he replied that for 50 quid he didn’t check anything.

Only recently I was shocked to see a double page feature about NATO in the Sunday Times which listed the membership of the organisation omitting Turkey. It was not even referred to in the body of the copy, and yet Turkey has NATO’s second largest armed forces. It seemed incredible to me that such a prominent feature could appear with such a glaring error. There was no fuss, no apology and worse still not even a clarification. It feels indicative of serious errors often spotted in so many publications.

One obvious cause for this is that few organisations can now afford to employ specialists in many areas. An exception remains the Financial Times, which continues to cover sectors of business admirably as well as breaking some major news stories — for instance, the colossal Wirecard fraud.

When it comes to broadcast journalism, we enter an altogether murkier territory. Any pretence of impartiality has largely evaporated from most channels. This trend began, like so much in broadcasting, in the United States. It was viewer-driven, thanks to a growing dislike of the endless wokery and left-wing bias of CNN. The multi-millionaire Anderson Cooper became synonymous with the nightly promotion of left-wing causes. So Fox News responded by becoming the overt voice of the right. Although other channels remained mostly liberal centre-left, the newsground was and is seen by Americans as a war between the two channels.

What happens in the US inevitably makes its way across the Atlantic. As viewers and listeners became incensed and bored by the increasingly left-wing approach to everything on the BBC and to ITV’s lackadaisical output, it was inevitable an alternative would present itself. In fact, two came along at roughly the same time: GB News and TalkTV.

These were rolling news channels with a more centre-right approach. At first, like any new broadcast venture, they did not seem to be catching the attention of the public but after a while both gathered momentum, coinciding with the rapid rise in popularity of the Reform Party led by a brilliant communicator in Nigel Farage. Piers Morgan was the catalyst for the original success of TalkTV, which he has now left to form his own outlet.

The BBC had finally got some real competition, which it did not like. It formed a ludicrous unit called BBC Verify which was set up to emphasise the broadcaster’s holier-than-thou approach to news, whilst at the same time its coverage of the war in Gaza has, with justification, been criticised for its acceptance of propaganda from Hamas and refusal to refer to it as a terrorist organisation, despite its being thus decreed by the UK and US governments. So often in recent years the BBC has sadly demonstrated that the news management of our national broadcaster can at times be both incompetent and biased.

The BBC has more foreign correspondents than any other news organisation in the world. They used to report with authority based on their deep understanding of the territory they covered, as well as information gleaned from high level contacts. For example, you may be old enough to recall the excellent Mark Tully reporting from India, a journalist who had a deep understanding of the country he was covering and who went out of his way to gain access to the people of power and influence. His reports were always illuminating.

With the exception of the laudable Steve Rosenberg in Moscow, the same cannot be said today. Correspondents rely on interviewing ordinary people in the street (or indeed each other), and it is rare these days to see a foreign leader interviewed. It was an extraordinary coup recently by Bev Turner of GB News to hold a one-hour interview with Donald Trump. It was a “soft interview”, nevertheless giving us insight into the mind of this mercurial president, something that the BBC has come nowhere near achieving, and now that they are embroiled in a lawsuit with him will never be able to do.

The BBC has so many problems that are well documented and discussed, but one in particular affects the whole of British journalism: the severe cutbacks in local television and radio. As the BBC struggles to fund itself, it has taken to cutting back in local broadcasting to such an extent that it is a shadow of its former self. Moreover, it is no longer a training ground for journalists to hone their skills and become national reporters. Although some schemes still exist, they are nothing to compare with those of the past.

With the radical reduction in opportunities with local newspapers as well, it means it is very hard to learn the craft of a news reporter. Although journalism schools still exist and you can take a degree in media studies, this training means little without a good dose of real-life experience beside them. I fear the situation will only deteriorate.

Instead of wishing to become a real reporter, young people will instead choose to be influencers on social media where they can do and say what they like and make a pretty penny at the same time. Even senior journalists have moved to become podcasters, where they can spout opinion without any actual news reporting.

It is approaching 50 years since the glory days of Harold Evans and Woodward and Bernstein. Genuine scoops these days are scarce, as nobody wishes to invest the time and resources to conduct the research often required. Even the grandly named Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Private Eye seem somewhat dormant in this mission, despite everything that is happening in this dangerous world.

I have been amazed by the seeming lack of interest or simply inability of US journalists to really get to grips with the story of Jeffrey Epstein, how he made such a fortune and why so many powerful people were seemingly so enchanted by him. What has been written has been predictably lurid, yet there is clearly so much more to this story.

There can be some optimism, however, that a new breed of journalist will emerge who will make a breakthrough as impactful as those of previous decades. A young journalist, Charlie Peters at GB News, recently produced a shattering report on the grooming gangs scandal which even generated praise from the House of Commons. Whilst standards have clearly declined significantly, there is an occasional glimmer of hope they could rise again.