The poised lawyer sitting across from me is signing books with practised efficiency, her pen gliding across title pages. When 60-year-old Astrid Holleeder looks up, I’m struck by how glamorous she is – but also by the facial echo of her brother, Willem ‘The Nose’ Holleeder – the most infamous gangster in Dutch history and the reason she has spent the past decade in hiding, ‘like a cockroach’, with no one knowing how she looked or sounded.

‘I’m so glad I have my voice,’ she tells me, her near-perfect English tinged with relief. ‘This was my voice for ten years’ – she gestures to her books – ‘but now I have my actual voice.’

The unseen, unheard Astrid Holleeder became one of the best-known women in the Netherlands when she turned star prosecution witness in the multiple murder trial of Willem, or ‘Wim’, making secret recordings of their coded conversations then sensationally testifying against him from a protective witness box in court.

That was a process that began in 2013 when she agreed to work with the Justice Department. But Wim had been a household name since the early 80s – most famous for his role in the 1983 abduction of beer magnate Freddy Heineken, who was taken from outside the company headquarters in broad daylight and chained to a wall for three weeks in a purpose-built soundproof cell. The crime was all the more audacious because Heineken, as well as being one of the richest men in the Netherlands, was their father’s employer.

There are four Holleeder siblings, of whom Wim is the eldest and Astrid the youngest. The age gap between them is seven years, and during Astrid’s childhood Wim was a tall, glamorous older brother who would go out late and shared their alcoholic father’s terrible temper. But he would occasionally present Astrid with gifts that alleviated the poverty of her circumstances. ‘If you are together with someone in that situation, you have a bond for life,’ Astrid has said of the violent household.

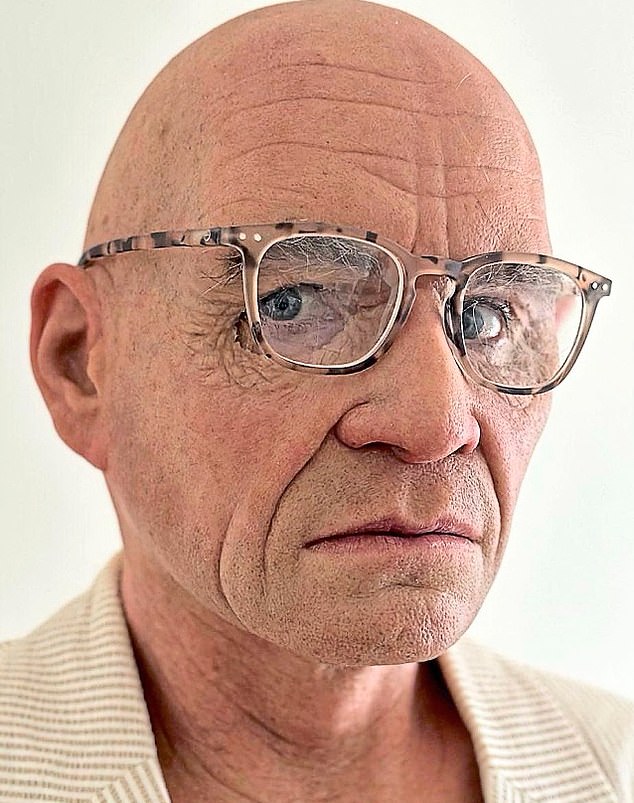

Astrid Holleeder at 60… she has spent the past decade in hiding after becoming the star prosecution witness in the multiple murder trial of her brother Willem, or ‘Wim’

One of Astrid’s disguises during the years she was in hiding

She was 17 and still a schoolgirl when news of the Heineken kidnapping broke. Ignorant of Wim’s participation in it, she was terrified to be woken in the night by a police SWAT team and locked in a cell. She was never charged with involvement but describes the episode as her family’s exit from respectable working-class society.

Wim served just five years in prison for the kidnapping, and the cartoonish audacity of the crime – a story that would be adapted into two major movies – allowed him to carve out a public image as de knuffelcrimineel, literally ‘the cuddly criminal’.

He appeared on talk shows and posed for selfies. ‘Everybody thought he was so nice, so showbiz,’ says Astrid, who knew the tyranny her brother was capable of, and regarded her association with him as the mark of Cain. ‘To this day, society sees me first and foremost as the sister of a criminal, from a mob family. The shame will always stick to me.’

What’s more, a sizeable portion of the ransom, which totalled 35 million Dutch guilders (or around £28million in today’s money), was never recovered. It is thought that Wim and his then partner-in-crime Cor van Hout, who was in a long-term relationship with the other Holleeder sister, Sonja, used the cash as seed money for a wide-reaching criminal empire.

‘They multiplied the Heineken money by dealing hashish in jail,’ says Astrid. ‘Hidden’ investments in various red-light-district establishments, mainly in Amsterdam – strip clubs, brothels, even an erotic museum – became an open secret. ‘I sold the tickets at the front desk of the museum,’ recalls Astrid of this period.

Wim, left, and Cor in court in Amsterdam in 1987… Cor would later be killed

Her brother’s criminality ultimately contaminated everything, including Astrid’s relationship with her partner Jaap who, after going to work for Wim in his vice operation, had multiple affairs, questioning Astrid’s sanity when she caught him out. Astrid left Jaap when their daughter, Miljuschka – now 40 and a well-known television personality in her own right – was still little.

Astrid was 23 and already a mother when she went to law school, hoping to be a corporate lawyer. But she soon learned on graduating that no one in that field wanted to hire a Holleeder. Wim came to her aid, arranging introductions with a top criminal defence firm, where the family name actually held cachet. Soon she started her own office, intuitively connecting with the families of her clientele and understanding their world.

‘I’m not the judge,’ she says of her guiding ethos. Then came the murders. At least five of them, between 2002 and 2006, with victims including Cor, Wim’s once-beloved compadre, after their relationship deteriorated. In fact, everyone who angered Wim seemed to end up dead.

So when he started talking about exacting ‘revenge’ on a still-grieving Sonja and her children – to his mind, they were unfairly living on the proceeds of his Heineken ‘work’ with Cor – Astrid knew he wasn’t joking. For all that she adored Wim, a line had been crossed.

Still, turning ‘snitch’ wasn’t Astrid’s default approach – at first she decided to do away with Wim herself.

‘I thought, I have to shoot him,’ she tells me matter-of-factly. ‘I’m the only one able to do that because I could get close to him. We were always side by side.’ What stopped her was the reaction of her daughter. ‘I said, “I have to kill my brother. I have no choice.” And she said, “I don’t want to have a killer for a mother.”’

Instead, Astrid acquired a small, wireless, voice-activated microphone from a spy shop and hid it in her bra. The resulting recordings, gleaned over months of tense meetings, would demonstrate to the Dutch public there was nothing cuddly about Wim Holleeder, a man consumed by paranoid rage. Ultimately, in the summer of 2019, he was found guilty of ordering five murders and one manslaughter and sentenced to spend the rest of his life in jail, which he is serving at a high-security prison in Vught.

Astrid had to give up her criminal defence work when she chose to turn witness and went into hiding – relying on elaborate disguises (‘an old, bald man’, see above) when she needed to go out. Even inside her daughter’s house, she had to maintain a charade when people were around: ‘I was the nanny or the cleaning lady.’

But the real hardship was the web of complex emotions. ‘I felt so guilty about him being in prison. So, in a sense, I took my own life, denying myself fun and happiness.’

She believes that her brother will use the time in prison to guarantee her demise – and that sooner or later he may succeed. ‘If somebody degrades him, he kills them. And that’s something he will never forget with me. That I degraded him.’

These days, the Jordaan district in the west of central Amsterdam is a chocolate-box neighbourhood of cool art galleries and expensive coffees. But in the 60s, when Astrid was growing up there, it was crime-ridden and dilapidated. She describes the Holleeder family home as a ‘theatre of fear’. Her father, the alcoholic Heineken employee, beat her mother. In her memoir Judas, Astrid describes being forced to eat her own vomit at her father’s behest.

Astrid as a baby in a family photo from 1966, with Wim on the far right

‘You have to be really crazy to do that,’ she reflects now. ‘That is something I only realised in the course of writing. I understood that my father wasn’t just an alcoholic. He was also a psychiatric patient.’

Astrid says it was an accident of birth that dictated the different paths she and Wim took. She describes the Jordaan of her youth as a world in which men and women occupied completely distinct spheres, ‘separate from each other even when they’re in the same room. The men sit with the men, the women sit with the women. There’s no equality in that subculture, by which I mean the mob culture.’

Consequently, there was never any prospect of Astrid becoming a criminal. ‘The only thing women in that culture can do is be pretty, dye your hair blonde, carry Prada bags and be obedient.’

Their mother exemplified this subjugation. She stayed in her abusive marriage, ‘and since my father was very traditional, she cooked and cleaned and wasn’t allowed to work. She had to follow him around and be obedient.’

In the final months of her life, Astrid’s elderly mother came to live with her – an especially intense reunion given Astrid’s isolation. ‘I couldn’t receive her friends or family – even a doctor.’ One day her mother became reflective: ‘How is it possible that I could have endured that for so many years? Every night, he beat me up. But not once I cried.’

Astrid was stunned by her mother’s apparent pride in her own invulnerability. ‘I was so mad because I was like, that’s how you were able to handle it, but what about me? I was a kid.’ She says the insight eventually brought her a sense of peace. ‘The only person that loved me my whole life is my mother.’

Both Astrid’s mother and grandmother had excelled at basketball but had to forgo the game for their respective marriages. Having inherited this sporting gift, Astrid recalls the time Wim pulled up in his sportscar and sped her to a make-or-break try-out she would otherwise have missed. Typical of Wim’s instinct for knowing exactly how and when to cement loyalty, this kind of intermittent reinforcement creates the strongest bonds.

Consequently, Astrid’s conflict is profound. She knows that Wim was the manipulator par excellence, yet she cannot relinquish his hold on her, nor can she escape the feeling that ‘it could have been me’ if she had been born male. She describes them having ‘the same aggression’, even ‘the same character’ and a common desire not to be the victim. The key difference between them, though, is ‘I seek justice. He seeks revenge.’

In August 2025, Astrid renounced her years of anonymity and introduced herself to the Dutch public in spectacular style, with a new role as a regular panellist on RTL Tonight, a nightly national talk show that she films at the RTL studios. At the time, she said, ‘I’ve been cut off from everything that makes a person human. I don’t even know how many times I’ve moved. Always running from that one fateful moment.’

Her role on the show is to provide expert commentary on criminal matters, both as a former defence lawyer and someone who knows the human cost of criminality firsthand. It has not escaped her attention that Peter R de Vries, the crime journalist who fell foul of her brother after writing a novel based on his investigation into Heineken’s kidnapping, was murdered in 2021 after leaving an RTL studio. Although De Vries had previously filed a death threat complaint against Holleeder, in the end he was targeted for having angered a different crime boss, Ridouan Taghi.

She points to a news story about another imprisoned Dutch criminal (known as ‘the murder broker’) who has been caught with a tiny contraband smartphone in his cell and may have been using it to take care of business as usual. ‘You see it all continues,’ says Astrid. Understandably, this kind of thing strikes fear in her heart. She takes sensible precautions: ‘I never make appointments.’

Despite the risks, Astrid called the move to reveal her identity ‘inevitable and necessary’. The catalyst, she says, was Instagram, where she has accrued 246,000 followers. After she joined the app in late 2024, using her real name but never revealing her face or location, she was touched by the kindness of strangers who knew her story and wished her well. Now she spends two hours a day replying to her followers, particularly those who are facing challenges. ‘I have a small community, and I can be something for them.’

Nevertheless, having turned 60, Astrid says she is determined to stop living in the past. A voracious reader, she ascribes to the tenets of the psychologist Alfred Adler, summarising, ‘you need purpose, community and responsibility’. Most of all, she chooses not to be a victim. ‘That would involve giving the power to somebody else,’ she says.

She hasn’t had any contact with Wim since his imprisonment, and I ask whether she thinks she will ever speak to her brother again. She pauses before replying that she already does, but only through her books, which are bestsellers. ‘He reads them, and he knows when I’m talking to him,’ she says.

Despite acknowledging that her brother is ‘a psychopath – if there are ten boxes for that test, he ticks 11’, she still loves him and the pain of their separation continues to smart. ‘If for one split second I could believe that he wouldn’t do harm any more, I would break him out [of jail] now.’

But since that’s not going to happen? She doesn’t hesitate in replying. ‘I hope he dies today – like this hour. Then he’s done, and he doesn’t have to suffer any more.’

Judas by Astrid Holleeder is published by John Murray Press, £12.99. To order a copy for £11.04 until 15 February, go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937. Free UK delivery on orders over £25.