This article is taken from the February 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

It’s never particularly pleasant when the theatregoing year starts with a stinker, but unfortunately Eric Roth’s new adaptation of the classic Oscar-winning western, High Noon, gives off a distinct odour of horse manure.

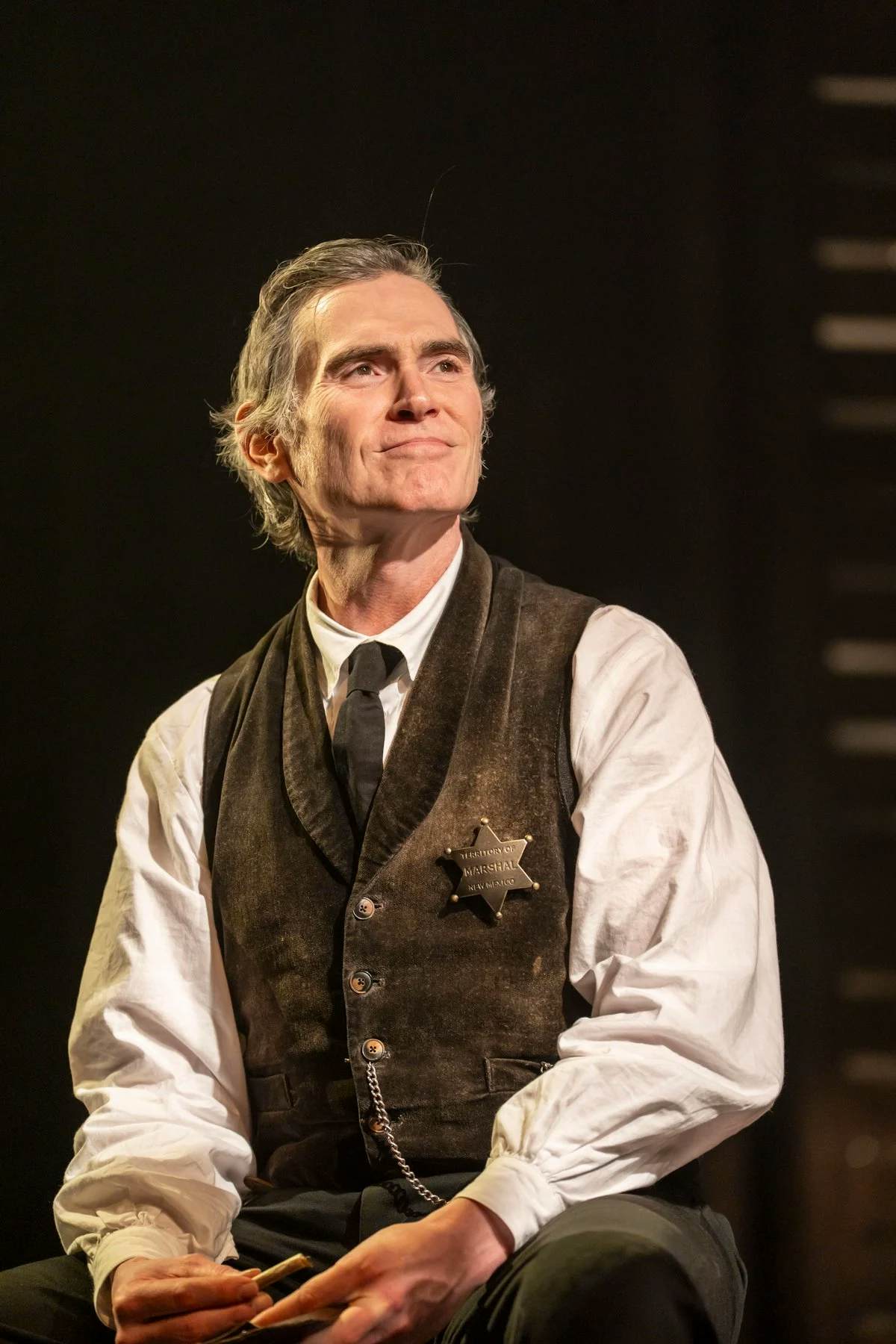

Despite a valiant central performance by that fine actor Billy Crudup, Thea Sharrock’s production is caught between a pervasive feeling of irrelevance and a sense that westerns, like science fiction and pornography, are a genre best left to film, as their essence cannot be captured on stage.

I fear, for all the undeniable talent and expense that has gone into this endeavour, this show will be facing its own showdown at the box office before very long.

It’s a shame, because Fred Zinnemann’s 1952 picture remains one of Hollywood’s greatest ever films, combining a nail-biting central countdown with a political subtext that was even more effective for its understatement.

In it, Gary Cooper played the ageing, honourable marshal Will Kane, about to hang up his spurs and marry his younger Quaker bride, in the beauteous form of Grace Kelly. Unfortunately, he receives word that his old nemesis, Frank Miller, has been released from prison and is coming to town on the noon train, bent on retribution against him.

As Kane tries and fails to persuade the townspeople to stand with him against Miller, he realises that the honourable ideals that he has spent his whole life upholding and protecting mean nothing to them and that, without a miracle, he is surely doomed.

It remains one of the exemplars of how to make a “message movie” without preaching. The message, of course, was an anti-McCarthyite one, with once-blacklisted screenwriter, Carl Foreman, attacking the idea of cowardice amongst the film industry, much to the disapproval of avowed Republican John Wayne, who was initially asked to star.

However, the film is now unthinkable without Cooper — who deservedly won an Oscar for his superb performance — and so Roth’s version of the screenplay offers the estimable Crudup a slightly different incarnation of the role.

His Kane isn’t the indomitable figure of righteousness that Cooper embodied but a more cautious, even timorous character, whose first instinct upon hearing of the imminent arrival of Miller is to skedaddle, bride on his arm: not a decision that Cooper’s upstanding Kane ever even contemplated making.

Crudup, last seen on the London stage in the acclaimed one-man show Harry Clarke in 2024, clearly likes his time in Britain, hence his relatively swift return.

It’s not hard to see what attracted him to this new version of the material, and what modest pleasures the evening affords are partially offered by him. (The others are obtained from the anachronistic use of some Bruce Springsteen songs, most notably the stirring “Land of Hope and Dreams” from his 2012 album Wrecking Ball, which is sung by the cast on stage.)

Whilst Crudup can “do” heroism and integrity, he can also do fear, doubt and despair, and, while he won’t erase memories of Cooper, he nevertheless gives an interesting, nuanced performance that could have been outstanding in a better show.

The downsides, unfortunately, are virtually everything else, beginning with Roth’s script. It is his first play, and although he is an Oscar-winning screenwriter who is responsible for everything from Forrest Gump and The Insider to Dune, the stage is not his forte. He seems incapable of building the tension and gnawing sense of fear that the ticking-clock narrative demands.

Instead, in a series of largely static scenes, characters windily debate whether or not they’re going to assist Kane, before invariably deciding that they won’t. Denise Gough’s Amy, newlywed and fearful that she’ll be an immediate widow, stands on the figurative and literal sidelines, occasionally bursting into mournful song.

There are some half-hearted attempts to toss in some anti-Trump allusions to update the political subtext — in a particularly on-the-nose bar scene, a character praises Miller as someone who “says what he believes and talks out of both sides of his mouth” — and both Amy and Rosa Salazar’s Helen Ramirez, a saloon bar owner and Kane’s one-time lover, are given greater amounts of agency in order to bring the narrative up to date.

Yet, not only does this feel painfully anachronistic, it is also unconvincing. There is seldom any sense that the characters on stage are behaving in a natural, authentic way; instead, they stand around underneath the ominously ticking clock and talk, and talk, and talk some more, before occasionally fighting, largely unconvincingly.

Tim Hatley’s set and costume design do at least convincingly summon up the spirit of 19th-century New Mexico, and, if Chris Egan’s music is often intrusive, in its favour, it does bring a bit of Morricone-esque spark to the show.

But Sharrock’s wishy-washy direction, Roth’s static script and some decidedly ripe supporting performances mean that this lacklustre update of a great film will undoubtedly be forgotten before very long.

If you want to see High Noon, go back to Zinnemann’s original and bypass this feeble midnight rambler of an imitation.

High Noon is at the Harold Pinter Theatre until 6 March