One of the first British patients to receive Elon Musk‘s controversial brain-computer implant has described what it is like to live with the futuristic chip.

Sebastian Gomez-Pena is taking part in the first UK clinical trial of the Neuralink device, which allows users to control a computer using only their thoughts.

The former medical student, who was left paralysed from the neck down after a devastating accident two years ago, told Sky News: ‘It is a massive change in your life where you can suddenly no longer move any of your limbs.

‘This kind of technology kind of gives you a new piece of hope.’

The billionaire tech tycoon has suggested the implant could one day be rolled out to the general public, saying his ultimate ambition is to create a mass-market brain-computer interface that would directly link human minds with powerful machines to achieve ‘symbiosis with artificial intelligence‘.

Mr Gomez-Pena, a keen cellist and rugby player, was in his third year of medical school when, aged 21, he dived into shallow water on holiday and struck his head, causing permanent spinal cord damage.

He is now one of seven participants in the UK trial assessing the safety and reliability of the device in severely paralysed patients.

Neuralink has said its mission is to ‘restore autonomy to those with unmet medical needs and unlock new dimensions of human potential’.

Sebastian Gomez-Pena, a keen cellist and rugby player, was in his third year of medical school when, aged 21, he dived into shallow water on holiday and struck his head, causing permanent spinal cord damage

Mr Gomez-Pena, a former medical student was left paralysed from the neck down after a devastating accident two years ago

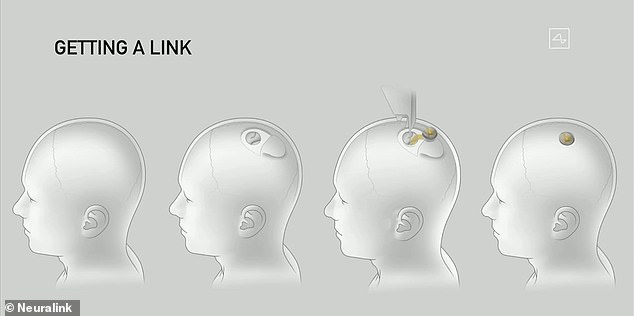

The implant was inserted during a five-hour operation at University College London Hospital, with British surgeons and engineers working alongside Neuralink staff.

The procedure itself was carried out by the company’s R1 surgical robot, designed to insert microscopic electrodes into delicate brain tissue with extreme precision.

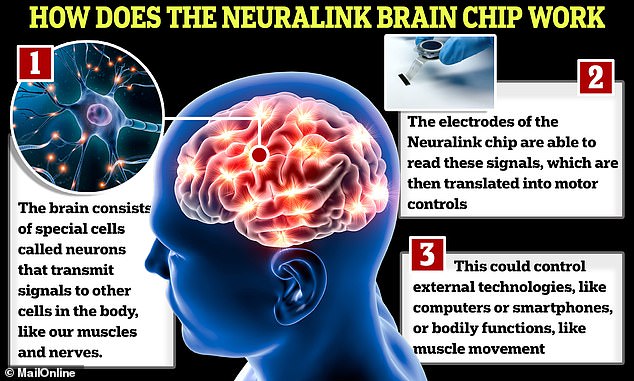

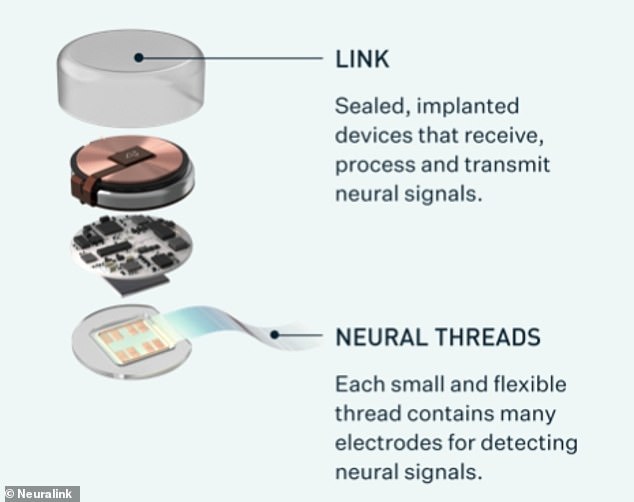

The device connects to 1,024 electrodes implanted around four millimetres into the brain’s surface in the area responsible for hand movement.

Ultra-thin threads – ten times thinner than a human hair – carry nerve signals to a small processor embedded in a circular opening in his skull.

From there, data is transmitted wirelessly to a computer, where artificial intelligence software learns to interpret his brain activity.

Once implanted, Mr Gomez-Pena simply thinking about moving his hand or tapping a finger can move a cursor or register a mouse click on a screen.

‘Everyone in my position tries to move some bit of their body to see if there is any form of recovery, but now when I think about moving my hand, it’s cool to see that… something actually happens,’ he said.

‘You just think it, and it does it.’

While controlling a mouse via a brain implant is not entirely new – early experiments date back decades – the progress has still impressed researchers.

Scientists have previously demonstrated monkeys and humans controlling robotic limbs, playing video games, and even shopping online using neural interfaces.

Even so, Mr Gomez-Pena’s doctors say his progress has been remarkable.

‘It’s mindblowing – you can see the level of control that he has,’ said Harith Akram, a neurosurgeon and lead of the UCLH trial.

Neuralink has tested the technology in 21 people across the US, Canada, the UK, and the UAE, all suffering from severe paralysis caused by spinal injuries, strokes, or neurodegenerative diseases such as ALS.

The first was Noland Arbaugh, from Arizona, who had his implant fitted in two years ago this month.

He has now been able to return to education, ten years after being forced to quit due to a paralysing spinal cord injury.

He is now one of seven participants in the UK trial assessing the safety and reliability of the device in severely paralysed patients

Once implanted, simply thinking about moving his hand or tapping a finger can move a cursor or register a mouse click on a screen

The procedure itself was carried out by the company’s R1 surgical robot, designed to insert microscopic electrodes into delicate brain tissue with extreme precision

The device connects to 1,024 electrodes implanted around four millimetres into the brain’s surface in the area responsible for hand movement

Elon Musk founded the company in 2016 with a group of neuroscience and robotics experts

‘I can’t even begin to describe how happy I am to be back in school,’ he said.

‘Not just passing my classes, but doing it in style.

‘This is literally the best semester of college (grades-wise) I’ve ever had.

‘[Telepathy] has given me back parts of my life that I thought were lost forever, and I’m finally starting to feel like myself again.’

Mr Akram said early results were promising.

‘This technology is going to be a game-changer for patients with severe neurological disability,’ he said.

‘Those patients have very little really to improve their independence, especially now that we live in a world where we are so dependent on technology.’

Neuralink also has plans to investigate reversing blindness by sending data from cameras, via the chip, into the brain’s vision-processing centres.

Accessing other brain areas involves implanting electrodes deeper into the organ safely and reliably, a challenge the company admits it has yet to overcome.

Yet Musk, Neuralink’s controversial founder, has greater hopes for the technology.

At an event last year, he floated the idea of users connecting their device to an Optimus robot made by his other company, Tesla.

‘You should actually be able to have full body control and sensors from an Optimus robot. So you could basically inhabit an Optimus robot. It’s not just the hand. It’s the whole thing,’ said Musk.

‘It’d be kind of cool. The future is going to be weird. But kind of cool.’