James works long hours day after day at a London nail bar in a street near the pastel-painted houses made famous by the wildly successful romcom Notting Hill.

He hails from Vietnam and arrived in Britain as a student three years ago when he was 29. He has never visited the West Country university that gave him a place on a computer course. And he never will.

For his student life is a sham. His visa was a way of entering this country to work and send money home to his family who live in a remote village where the average weekly wage is £29.

He is here illegally because his Government-authorised study visa expired a year ago. He travels into Notting Hill from a flat in the East End, which he shares with other Vietnamese migrants – many of them so-called ‘students’, too.

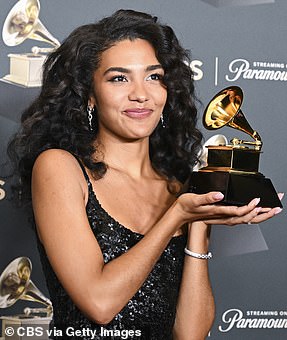

Each week James uses a money company, Remitly, to transfer ‘between £40 and £60’ to his mother who speaks to him regularly over the internet, asking him relentlessly: ‘Have you found a nice wife in London yet?’

James – the anglicised name he gives himself so his predominantly English-speaking customers feel comfortable – is one of hundreds of thousands of migrant workers sending money back home to their families abroad.

‘It helps my mother,’ he says simply. ‘My family collected together the £1,250 to buy my UK student visa and pay the tuition fees upfront. They knew I was not here to study, but to earn. The university doesn’t ask where I am. It was a cheap way for me to work in the UK.’

Across the road is a hairdressing studio where three Indian girls – in their 20s with pitiful English – work several hours a day and sleep in a shabby flat beneath the property.

The popular money company Remitly is often used by illegal migrants, like student visa holder James from Vietnam, to send money back to their home countries

Critics of uncontrolled immigration argue that benefits and the chance of illegal work attract people to Britain.

They are student visa holders, too. They go online four hours a week ostensibly to get Master’s degrees in business administration at a London college with a postal address near the British Museum.

Every week, the trio wire money to their parents while living frugally in Britain.

‘We feel lucky to be here,’ one of them, called Maya, explained. ‘The daily wage back home is £1.47, so my father, a market trader, needs the extra money.’

James and Maya are two of the millions of foreigners in Britain sending money home. But there is a darker side to the so-called remittances sent out of this country by migrants of all sorts, whether honest workers, illegals or those living on welfare benefits.

Critics of uncontrolled immigration have long argued that benefits and the chance of illegal work are a pull factor attracting people to Britain.

True enough. But the prospect of being able to easily wire money back home is surely the strongest lure. The sums involved are extraordinary. The respected Migration Observatory at Oxford University says £9.3 billion was dispatched to countries around the world from the UK in 2023, a £2 billion uptick on two years earlier.

Yet the Observatory says this is a staggering underestimate. It points out that the World Bank believes remittances from the UK stood at a mind-blowing £24.5 billion in 2021, more than twice Britain’s foreign aid budget of £11.4 billion for that year.

The scandal is that no one in Government counts the remittance figures, so those who ask don’t – or can’t – get answers.

Posters like these in Walthamstow, London, advertising money remittance services are increasingly common. An estimated £9.3billion was sent to countries around the world from the UK in 2023

Husband and wife Petru and Ancutu Neagu, said they send money from London to Romania for their four children, aged between one and seven

To add to the difficulty of calculating the amount, we do not know how many illegal migrants are in the country, even less how much money they are sending home.

Since the end of foreign exchange controls in 1979, there have been no official mechanisms for recording international money transfers, including remittances.

‘A significant proportion of them may occur through unofficial and unrecorded channels, such as friends and relatives “carrying cash on their travels”,’ comments the Observatory.

This week, Professor Carlos Vargas Silva, an economist at Oxford University’s Centre on Migration, Policy and Society, told the Daily Mail: ‘There is almost no reliable recent research into what sources of income make up the remittances being sent from the UK – whether that is from earned income, welfare or other ways that people may have made their money.

‘This makes it challenging to understand the impact on our economy.’

Whatever the case, there is no doubt that huge sums are wired or transferred out of the country by immigrants enticed here by the laissez-faire remittance system.

It means billions and billions of pounds are not being spent on high streets, invested in British savings accounts or paid in VAT to the Exchequer. At a time when the economy is struggling, it is billions of pounds annually that could benefit the country.

In President Trump’s America, the penny has dropped. The US state department has frozen visas to nationals of 75 countries, including Pakistan, in a bid to bring an end to the outflow of funds from America, which in 2022 reached £640 billion.

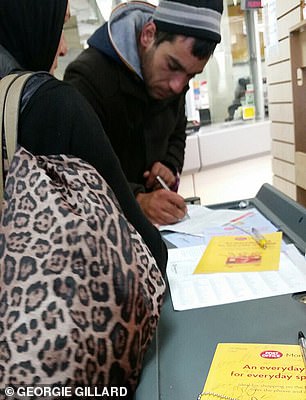

Petru begs on the pavement outside Selfridges with a pink walking stick, pretending to be disabled to get more cash in his tin. He is later seen sending his profits back home to Romania at a post office in Edgware Road, London

All remittances from Cuban migrants to their Communist run island, where 70 per cent of citizens survive on them, have been suspended. US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent is to widen curbs further. Every migrant on welfare is to be barred from wiring out money to protect the US economy.

‘There will be no more funds leaving for abroad at the expense of the American taxpayer,’ his department said a few days ago.

Here in Britain, a quarter of all non-EU migrants (whether here legally or not) send remittances home, with Pakistan, India and Nigeria topping the list of destinations.

A report by the money transfer giant Western Union two years ago stated openly: ‘For many who move to the UK, being able to send money back is one of the primary reasons why they choose to relocate here.’

Astonishing figures show that in 2024, the State Bank of Pakistan received £3.3 billion from the huge diaspora of two million people of Pakistani heritage living in the UK.

This was 15 per cent of all global remittances to Pakistan, where money sent from abroad props up the economy and represents 9.4 per cent of the country’s GDP.

The question is where did these billions sent from Britain come from? It is highly likely some of it is from benefits paid by UK taxpayers.

Since almost half of people with Pakistani heritage in Britain receive some form of state support and up to one in three are either out of work or not seeking employment, it is improbable that none came from UK state handouts, a system already creaking under a huge strain.

As far back as 2010, the then Labour MP Harriet Harman, who published a report on remittances in her Camberwell constituency in south London, claimed that ‘heroic’ migrants claiming benefits in the UK were routinely sending money abroad to support family members.

And the anecdotal evidence suggests it is still going on today. In 2024, there were 10,542 asylum applications filed by Pakistanis, higher than any other nationality, even though the country is deemed safe by the Home Office.

When the figures were revealed, Harjap Bhangal, a UK-based immigration lawyer, said: ‘They don’t need to come on small boats because they come on visas, claim asylum and don’t go back. The Home Office is a broken institution. They do not realise the loopholes or what the migrants are doing.’

A Romanian woman begs in Southwark in London, during icy winter conditions

An advertisement for Remitly is displayed on the side of a London taxi

He added some detail: ‘There is a trend for Pakistani students to get a visa and come over, then claim asylum once they are here.

‘We see those who don’t actually go to university. There are also people who come on healthcare visas and then don’t work… the idea is once you get through immigration [with a visa] you can claim asylum.’

Another source of the money haemorrhaging from Britain is crime. HMRC warned last year that £2 billion leaving the UK annually is likely to be through ‘informal routes’ (such as cash stuffed in suitcases or via backstreet money agents) used by criminals to launder their spoils or even those funding terror organisations in rogue nations abroad.

The legal UK remittance system works by allowing senders to wire funds using a mobile app or via money transfer shops (of which there are now many in the UK) for cash pick up at agencies or banks abroad.

I followed a gipsy couple one Monday morning to a post office near Oxford Street and, with the help of an interpreter, filmed them counting out £800 of their weekend takings from begging in central London to send by MoneyGram to their home city of Iasi in eastern Romania.

When I approached Petru and Ancutu Neagu, then aged 29 and 25, they told me the takings were for their four children, aged between one and seven, who were being looked after by Ancutu’s blind grandmother.

‘If we could not provide for our children, there would be no reason to be here’ said Petru simply.

Within an hour of making the MoneyGram transfer, the couple were back sitting on the pavement outside Selfridges with their hands outstretched, as though destitute. Petru, incongruously, was waving a pink walking stick to pretend to be disabled and get more cash in his tin.

Even the most destitute manage to send home money. Recently, I visited a migrants’ hotel in Crawley, East Sussex, and found that many of the young men, a good number of them fresh off the Channel boats, had apps on their mobile phones to transfer money back home to the very countries they have fled from, apparently because of the terror and trauma they suffered there.

While waiting for their asylum claims to be heard, they are receiving a Government handout of £43 a month, effectively pocket money to spend as they wish because everything else, from their laundry to their three meals a day, heating and roof over their heads, is free.

It may sound a pittance, but it isn’t back in the Sudan where many migrants come from and where the average monthly income is just £6.

‘Yes, I already sent money to my parents,’ said one 27-year-old who I talked to outside the hotel.

‘If I could work, which I want to, I would send more. It is for my family to survive, to buy food, to let my little sister go to school.’

He came from the capital Khartoum and arrived on a Channel boat in September, one of 1,500 Sudanese men who lived in a former warehouse in Calais which was cleared by the French government in the autumn with almost all immediately making their way to the UK.

I have also discovered that Albanians coming here illegally think it is perfectly normal to send money home. I have regularly visited the town of Has, tucked away in Albania’s mountains, where almost all the young men have left for England.

Yet another Remitly advert, this time at a station on the London Underground

…and another on the side of a London bus, advertising the company’s services

Out of the working-age population of 5,000, only 700 have jobs, 300 of them in the public sector as police officers, civil servants or teachers paid for by the state.

As a teacher from the secondary school told me last year: ‘The residents left behind rely heavily on money sent back from the UK by their sons in order to make ends meet.’

In 2016, Romania’s ambassador to the UK said in Parliament that £7 billion a year was being funnelled back to his country by Romanians then settled here. Today, of course, the figure will be far higher.

When I met one young Albanian in east London recently he said, quite openly, that he was working illegally on a building site.

‘I have not claimed asylum. I know I would not get it. I came on a Channel boat and was sent to a migrant hotel where my cousin picked me up after 24 hours and I disappeared.

‘I stay here for one thing,’ he added politely. ‘To work hard and send money to my family who need it in Albania.’

No wonder the Romanian beggars Petru and Ancutu believe it is all worthwhile to up sticks and come to the land of milk and honey. Outside the Oxford Street post office after sending the MoneyGram transfer, they told me: ‘If we did not do this begging in London, our children would have nothing to eat.’

Then Ancutu rubbed her stomach proudly. ‘We have another child on the way,’ she added.

‘Five children are a lot to look after and once this baby is born we will be back in Britain to beg and send our money home because he or she will need feeding, too.’