Whether Andy Burnham will be allowed to run comes before whether he’ll win, of course. There’s always that delightful possibility that he’ll be beaten by Gorgeous George. But rather more worrying, for me, is his insistence that he knows what’s gone wrong in Britain — that we need to “re-industrialise the birthplace of the industrial revolution”, thus “bringing high-value employment”.

Sadly, no, that’s not the way it works — and it’s also not what happened either.

If your view of reality is completely orthogonal to the truth then your solutions are going to be wrong

It’s possible to be argumentative about his other four claims — that what went wrong involved “deregulation, privatisation, austerity and Brexit”. (I didn’t just argue but worked for two of those.) So, the idea that modern Britain has less regulation than it used to is absurd. Austerity, meanwhile, never actually happened. Government spending, taxes and the deficit — the gap between them — are all up at peacetime highs whether we measure in cash terms, real terms (thus adjusting for inflation) or as a percentage of GDP. There simply isn’t any way that spending declined — not unless we’re going to have austerity mean “less than I’d like to have spent”, which is a current usage to some but also one of no great analytical value.

The part of this that really worries me, though, is the deindustrialise part. For this is to grossly misunderstand what actually happened. It misunderstands it to the point of getting it entirely wrong. Arse about tit. And if your view of reality is completely orthogonal to the truth then your solutions are going to be wrong.

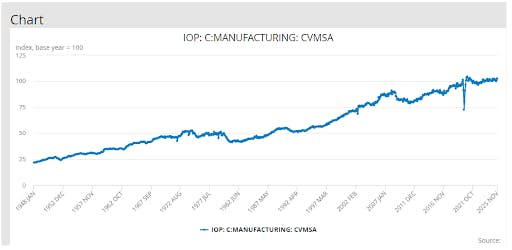

This is the index of manufacturing:

It’s the value of UK manufacturing output over time. It’s an index so yes, it already is inflation adjusted. This is also not the index of production, which would include mining and North Sea oil. As we can see, manufacturing output was higher when St Maggie left office than when she entered it. It’s also substantially higher now than it was then, and some four times higher than what it was in 1950 when all workers had flat caps and made whippet flanges.

The UK simply has not deindustrialised, so therefore there’s no need, or even sense, in re-industrialising it. The “no sense” part comes from the fact that manufacturing is not, particularly, high-value employment any more. Current average manufacturing wages are about 10 per cent higher than services but that wouldn’t survive any significant expansion of the sector. As with that mistake made about the universities — graduates make more, so if all become graduates then all will make more — life just doesn’t work that way.

What did happen is that manufacturing shrank as a percentage of the economy. We can mourn that if we wish, but it’s also true that it has happened everywhere. Actually, by most measures, manufacturing has fallen as a percentage of the global economy. It’s also true that manufacturing employment fell as a percentage of all employment. That’s something that has been happening even in China in recent years too. The reason for this is nothing to do with neoliberalism, St Maggie nor even the triumphs of the financiers. It’s because the NHS needs ever more money.

Or, rather, the reason the NHS always requires more money is the same as the reason that manufacturing employment has fallen even as output has risen. It’s a standard observation that the NHS does require a 4 per cent per annum rise in real budget just to stand still. This is the point at which economists shout, in unison, “Baumol!”

Baumol’s Cost Disease is the observation that it is easier to increase productivity — here we mean labour productivity, so we mean producing the same with less labour and producing more with the same labour — in manufacturing than it is in services. In manufacturing, we can always design a better machine to do the work for us, but services can be usefully defined as actual human labour being devoted to the provision of that, erm, service. So, to increase service productivity, we have to work out how to mechanise a part of it. We cannot improve the productivity of the string quartet by whipping them — or conducting them, to musicians there is little difference — into playing faster but we can invent the phonograph and mechanise music production.

We should also note that average wages are determined by average productivity across the economy. This is not something in doubt among economists.

The joint effect is that services will become more expensive, relative to manufacturing, as productivity improves. Or, the same statement, as the society gets richer. Getting richer is higher wages, higher wages are getting richer. So, we’ve got to pay higher wages right across the society as the society gets richer — but labour productivity is increasing in manufacturing faster than in services. The labour embedded in services thus increases the costs more than that in manufacturing. This is what explains the NHS and its thirst for budget — medicine is largely services, straight human time and effort.

All of this is well known among economists and the brighter lefties have picked it up too — it’s an argument for a larger NHS budget after all. It’s even a correct argument for a larger NHS budget.

The thing that annoys me is in how few grasp the other side of this very same point. Which is that of course manufacturing employment falls over time — because this is the same thing as the NHS needing that extra 4 per cent a year. Because we increase productivity in manufacturing therefore we need to use less labour in manufacturing. This is also what allows us to grow the NHS of course — we now require less labour on the whippet flange presses therefore we can staff the wards.

It’s also what happened to agriculture over the centuries. There was a time when we needed 90 per cent of people in the fields to just grow enough food for everyone. Then came the tractor and we now use 2 per cent of the population. We’ve added 88 per cent of the population to the workforce that can do everything else other than farm. We can take that to an extreme and insist that it’s the tractor that created the NHS, for without increasing agricultural productivity we couldn’t have 13 per cent of the population NHSing.

The decline of manufacturing as a percentage of employment, as a percentage of the economy, is just one of those things. It is an entirely natural process and as such something that doesn’t need to be reversed.

Which brings me back to that original observation that there’s a lot I disagree with Burnham on — Brexit and privatisation as examples. But that’s as nothing to the worry I have about potentially being ruled by someone who doesn’t even understand reality.