The rules-based order might have been based on fiction but fiction is essential in politics

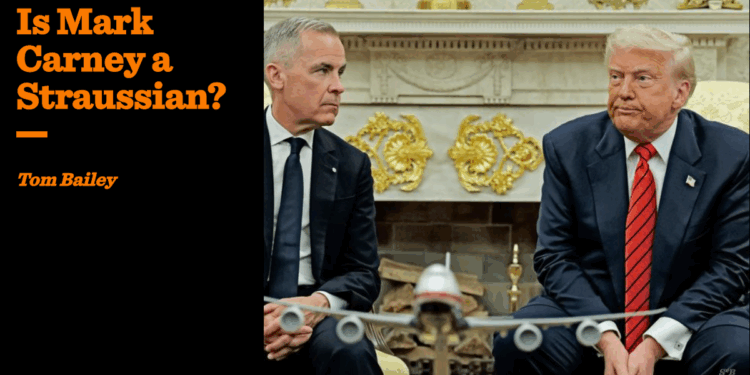

Global leaders and assorted bigwigs at Davos have spent the last few days decrying the end of what is variously called the “international order” or the “rules-based order”. Some have celebrated its passing. Others have mourned it. But few were as clear-eyed about the change as Mark Carney.

In his speech, the former central banker and now Canadian prime minister argued that the idea of a rules-based international order was always, at least in part, a fiction. International law was applied unevenly and an asymmetry in power was always lurking in the background. But, Carney argued, going along with this fiction was itself beneficial.

His remarks point to a Straussian logic of myths being a feature of order

As Carney argued, American hegemony underpinned the order while also at times ignoring it. But it also supplied public goods in the form of open sea lanes, a stable financial system, some form of collective security. Countries participated in the rituals of this order because they understood that alternative was worse. Shared belief in this partial fiction produced a more stable and prosperous world than had existed before.

It is hard to argue with this. The willingness of the United States to guarantee free and open shipping was historically anomalous, at least absent a formal empire demanding tribute. The global taboo on the annexation of neighbouring territory, underwritten by American power, was also unusual. Countries have plenty of incentives to take other’s land (resources, co-nationals stranded as minorities, strategic locations) yet for decades this impulse was checked by the understanding that America would not approve and might intervene. That this required turning a blind eye or offering resigned acceptance when the United States itself acted outside international frameworks was part of the bargain.

Carney’s reading of the system is almost Straussian. Leo Strauss, drawing on Plato, argued that societies are held together by sustaining myths (or “noble lies”) that are not strictly true but are needed for order.

This is not the first time Carney has shown an air of Straussianism. That is, an instinctive understanding of how systems rely on collective belief. The collapse of Woodford Investment Management in 2019 provides a useful parallel.

Neil Woodford had built a formidable reputation over decades as one of Britain’s most successful fund managers. When he left Invesco to launch his own firm, billions of pounds of retail money followed. The flagship fund promised daily liquidity, meaning investors could withdraw their money daily. But the fund owned a growing share of illiquid assets such as companies not listed on a stock exchange and therefore not able to be easily sold. When performance faltered and redemptions accelerated, Woodford was unable to sell those illiquid holdings quickly enough to meet investor withdrawals. Instead, he had to sell his more liquid stocks, typically big companies listed on the London Stock Exchange. As a result, the liquid portion of the portfolio shrank and the illiquid share rose, creating a compounding spiral. Eventually the fund was gated, meaning investors were banned from withdrawing their money before eventually being wound down.

This was a familiar story of liquidity mismatch. Open-ended funds allow investors to redeem daily. That works smoothly if the underlying assets are easily saleable or, even if some of the portfolio is illiquid, investors themselves do not fear an inability to withdraw their money. It breaks down when they are not. What made Carney’s intervention notable was the language he used in the post-mortem to Parliament, claiming such funds were “built on a lie”.

We can understand Carney’s phrase here as less meaning an outright lie than an assumption or a collective belief that daily liquidity is always available. That assumption holds so long as investors believe it and behave accordingly. Once that belief falters and behaviour changes the structure is thrown into doubt.

Carney’s blunt comments showed an understanding that the functioning of open-ended funds depended on a belief in a promise that was only conditionally true.

Whether Carney has read Strauss is unknowable and ultimately irrelevant. What matters is that his remarks point to a Straussian logic of myths being a feature of order. His “built on a lie” comment, read alongside his comments on the international order can be read as an instinctive recognition that in both finance and geopolitics, stability depends on collective acceptance of partial fictions. They work until they don’t. The question is now whether “pleasant fiction”, as Carney called it, can return or whether the world will have to be more honest with itself.