The word “assimilation” belongs to the migration discourse of a much earlier era, roughly the late 1940s to the mid-1960s. Of course, in those years immigrants to Britain typically came from the Commonwealth, and so to some degree had already been exposed to British cultural norms. “Assimilation”, as used by MPs, civil servants and commentators, expressed the view that immigrants should and would fully adopt those norms, along with British values and behaviour. It explicitly meant immigrants changing to fit into British society, without any reciprocal change on the part of native Britons either expected or desired.

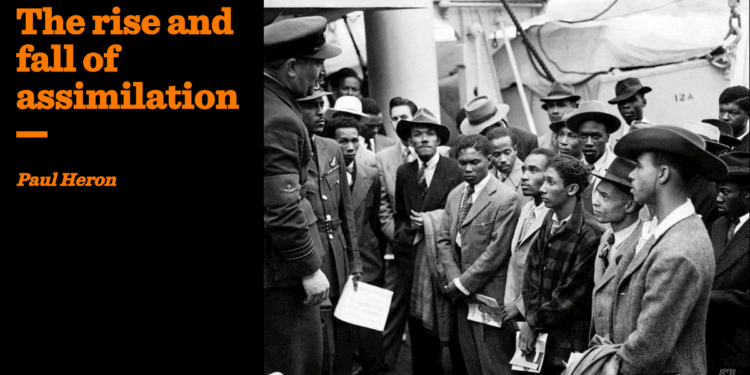

To an unprepared Britain forced to get to grips with Commonwealth immigration quickly, assimilation seemed a reasonable, even a generous demand. This new era had, as it were, ambushed the country —- the almost five hundred West Indians who arrived on the HMT Empire Windrush in June 1948 were technically uninvited, and the legislation that would formally grant them and all other colonial subjects British citizenship, the British Nationality Act, was then still over a month away from receiving royal assent. If Clement Attlee’s own words are to be trusted, encouraging mass immigration does not seem to have been among the government’s intentions with the Act. In a letter to eleven concerned Labour backbenchers, dated July 5th 1948, the PM stressed that under existing law it was:

… traditional that British subjects, whether of Dominion or Colonial origin (and of whatever race or colour) should be freely admissible to the United Kingdom.

He cautioned against seeing the Windrush arrival as the start of a large wave of migration, saying it would be “a great mistake to take the emigration… too seriously”. Attlee emphasised the migrants could alleviate labour shortages a little, but doubted large influxes would follow.

That West Indians identified with Britishness to this degree was a measure of how effective colonial education had been

In that unsuspecting summer of 1948, “assimilation” was on nobody’s lips. Even so, the arrivals from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados and other Caribbean colonies appear to have understood the notion instinctively. Smartly dressed when they disembarked on June 22nd, a day after the Windrush’s much-publicised arrival at Tilbury, the West Indians gave every appearance of wanting to make a good impression. A Pathé News camera unit was present to capture these exotic arrivals — mostly but by no means exclusively men — in their Sunday best. They answered journalists’ questions politely (even musically, in one case). According to black British writer Colin Grant’s oral history Homecoming: Voices of the Windrush Generation (2019), these first immigrants’ respectful demeanour and attire reflected how most West Indians felt toward what they regarded as ”the mother country”: deferential, admiring and affectionate, though to varying degrees, as one would expect. Grant’s mother was of the Windrush generation, and the way the author tells it, her attitude was not uncommon:

Ethlyn, like many of her friends in Jamaica, had a romantic attachment to the notion of England as a motherland. The values of England were her values; her belief in England was an article of faith … Ethlyn immersed herself, 4,000 miles away, in a fictionalised idea of Britain found in Tom Brown’s School Days in particular. That quintessentially British novel, film and culture held a grip on her imagination and that of her peers.

Besides this romantic image and the ambitions they hoped to fulfil, many of the Caribbean men and women who made their way to Britain over the next fourteen years — up until the restriction of immigration in 1962 — were motivated by the conviction they had a right to call themselves British, a belief that predated the British National Act but which, naturally, was bolstered by it. Grant recalls how, whenever he talked about being “British by birth but Jamaican by will and inclination”, he would be set straight by his father:

Stop talk tripe. You born right here. You are English; I am British. Now let’s get that straight.

Though he “never really expressed much enthusiasm for Britain”, Grant’s father:

… had an uncomplicated attachment to his moral right to be here. His British passport bore the stamp: ’Right of Abode’. And so what more was there to discuss? ‘Argument done,’ as Jamaicans say.

That West Indians identified with Britishness to this degree was a measure of how effective colonial education had been. Although not all of Grant’s interviewees remembered this schooling fondly, I was struck, reading about it, by the impression that here was a truly self-assured nation, one that believed in its achievements and felt no obligation to apologise for anything. This is how one Waveney Bushell (seemingly named after the river) put it:

We were indoctrinated into feeling that Britain was the place in the world. When you think of literature, up to the days when I was doing teacher training age nineteen, twenty, I would say that until then I felt everything English was the best, for example was better than American…. We somehow got the impression that these English books were better – that the English people spoke was somehow superior to the English that the Americans spoke.

Another interviewee, Arthur France, recalls the high esteem British-manufactured products were held in:

It’s like magic to see ‘Made in England’’and people cherished things from England. Like a car, Austin of England, which was one of the cars Daddy used to drive. When they see something ‘Made in England’, that was it, you don’t ask any more questions.

Most West Indians had an idealised image of Britain. Unsurprisingly, for many of the almost half a million who undertook the trip to the mother country between 1948 and 1970, actual life here did not live up to that perfect picture. Homecoming draws upon a much earlier book of interviews, Donald Hinds’ Journey to an Illusion (1966). That melancholic title is unequivocal.

But why were some migrants’ experiences so unhappy? Grant says the West Indians had an “initial headlong focus on the wisdom of assimilation”, and that, of course, came with trade-offs: assimilating must necessarily mean discarding elements of their own culture and identity. Furthermore, many natives simply didn’t want the West Indians in Britain, and had only scorn for their attempts to assimilate. Though already obvious, this was underscored by the Nottingham and Notting Hill race riots of 1958, when Caribbean migrants battled white youths, some of the latter sporting teddy boy attire. The Notting Hill disturbances were the most serious instance of racial disorder in Britain until the riots in Bristol (1980), Brixton and Liverpool’s Toxteth (both 1981).

The 1958 riots fed Conservative doubts about the wisdom of immigration. Growing unease in Westminster and across the country at large led to the Commonwealth Immigrants Act 1962, which made a work permit a requirement for residence. Since this document was typically issued only to high-skilled workers like doctors, immigration was reduced from 136,400 in 1961 to 57,046 in 1963.

At this time, the early-mid 60s, the language used to discuss immigration was changing, reflecting a shifting view of what was to be expected from immigrants. The word “assimilation” was falling out of favour, giving way to “integration”. Only a minority of the governing class still expected immigrants to simply adopt British ways wholesale. Left-liberals had come to see that demand as unfair, while many conservatives accepted it as unrealistic. “Integration” meant immigrants could retain their own distinctive culture provided it was compatible with British society. And of course, they would still have to adopt the essentials of British life: to learn English (if applicable), respect British traditions and institutions and be productive, law-abiding citizens.

How immigration came to be seen by most Western governments as economically essential and socially workable — in other words, as a positive good — becomes clear when one examines the climate of global opinion in the immediate postwar period.

The war and its outcome had discredited most right-wing visions of progress and civilisational renewal — in particular, those that had been defined by scientific racism, Nietzschean morality and eugenics, plus in some cases mysticism and the occult. In short, anything Fascist or Fascist-adjacent was out, so while the progressive eugenics of Fabian George Bernard Shaw were very much cancelled, Ayn Rand’s Objectivism, by virtue of being sufficiently distant from Fascism, escaped.

Universalist conceptions of progress and renewal now had the upper hand, and that meant anti-racism, egalitarianism and secular humanism were very much on the global agenda. From 1945 on the social sciences and multinational organisations like the newly founded UNESCO heavily downplayed racial differences, in effect denying there was anything innate about them. In UNESCO’s case this was done to further the agency’s project of “a single world culture, with its own philosophy and background of ideas.” That is how it was put in 1946 by Julian Huxley, biologist brother of Aldous and UNESCO’s first Director-General. For Huxley, “scientific humanism” should form the basis of that universal culture. The UNESCO head had great faith in science. In 1945, he’d proposed using atomic bombs to melt the polar ice caps, thereby achieving two things: moderating the northern hemisphere’s climate and permitting shipping across the top of the world. Perhaps it was suggestions like that, or more likely his left-wing politics, that led to his tenure as Director-General being cut short: Huxley was removed from the post in 1948 at the behest of the Americans. Nevertheless, UNESCO continued in much the same spirit, in 1950 issuing a radical Statement on Race. Perhaps its most striking claim was this:

The biological fact of race and the myth of ‘race’ should be distinguished. For all practical social purposes ‘race’ is not so much a biological phenomenon as a social myth.

It went on to explain that this myth had caused enormous human and social damage and hindered cooperation among peoples. A second statement, emphasising that intelligence and moral capacity were not linked to race, followed in 1951.

UNESCO’s position was radical, but the wider world was drifting toward it. The USSR was ahead of the curve, having been officially anti-racist since 1936 (equal treatment was written into its constitution of that year). With the Soviet Union at its head, global communism’s anti-colonial agitation and deep involvement in insurgencies throughout Asia, Africa and Latin America helped anti-racism make strides in the later 40s and the 50s. By the mid-1960s racism had become a low-status, disreputable stance throughout what had become known as the First World. Though this was officially true throughout the Second World too, discrimination against minority groups was still a tacit reality in the USSR and China.

A feature of the anti-racist position was the confident belief, or at least claim, that what had come to be called the Third World could successfully modernise — i.e. that its newly independent countries could, in time, not only reach the level of the First and Second World nations, but broadly mirror them in their culture. Julian Huxley was far from alone in his belief in the possibility of a universal civilisation.

For the faithful, there were promising signs aplenty: with decolonisation proceeding apace, a generation of Third World leaders was emerging who, whether they aligned their fledgling nations with Communism or what liked to call itself the Free World, dressed in conspicuously modern attire and spoke in broadly the same secular, technocratic terms as Kennedy, Khrushchev, Wilson and de Gaulle. Leaders such as Egypt’s Nasser, India’s Nehru, the Shah of Iran and a host of others pursued modernisation with material resources and expertise supplied by their superpower patrons. These leaders were also keen for their countries to be seen as secular and modern (hence all those mini-skirted Persian women that populate the “Iran before the Revolution” memes). Against this backdrop of a world apparently embracing the rationalism of the Enlightenment, modernising in accordance with universalist models (be they of First or Second World origin) and consigning racism to the dustbin of history, hopes were high in Europe and North America that the integration of immigrants would be successful.

Given the relative success of colonial education and the need to maintain good relations with the Commonwealth, plus the supposed demand for cheap labour, it’s easy to see how much of Britain’s governing class, those left-of-centre in particular, could have persuaded themselves that, in a world embracing universal ideals, immigration could surely be made to work, indeed was working. But if integration required less of immigrants than assimilation, even its more modest demands struck British sceptics as delusional, as the transcript of a 1964 Commons debate on Commonwealth Immigration shows. Here is the Conservative MP for Liverpool Kirkdale, Norman Pannell (misspelled as “Panned” in the transcript), a prominent critic of immigration at that time:

The only long-term justification for immigration is that the immigrant will, in the course of time, be fully integrated into the life of the nation.

Pannell then lists some examples of successful integration: Flemings and French Huguenots in the 16th and 17th centuries, refugees from Germany, Austria and Poland more recently (“But they are all of European stock, which simplifies the problem”). Further on he explains how, in his view, integration is achieved:

The only thorough method of integration is by inter-marriage with the indigenous population over the generations. That has occurred with European immigrants, but the problem is much more difficult in regard to immigrants from Africa and Asia.

Pannell even comes close to anticipating Britain’s future membership of the EU:

I am afraid that I am about to utter a complete heresy, but if there is the need for labour—and I am not always certain that there is, and that we could quite probably make do with the labour we have—I think it preferable to import short-term labour from the Continent, which would return at the end of the contract, rather than import unassimilable immigrants on a permanent basis.

Although increasingly restrictionist legislation was brought in over the next two decades (the Acts of 1968, 1971 and 1981), in time the Norman Pannells of Britain were squeezed out. Talk of integration made way for today’s language of multiculturalism and diversity, concepts which imply that almost nothing whatever is now demanded of immigrants (as is well known, even law-breaking is tacitly tolerated to some extent). Labour has attempted to wipe away the stain of the 2018 Windrush scandal by making June 22nd Windrush Day, which of course also serves a propaganda purpose. Last year, in an inflation of rhetoric from previous years, Keir Starmer tweeted that the Windrush generation were “pioneers who rebuilt Britain”. He also claimed that they “laid the foundations for modern Britain”.

These are absurd exaggerations, but it would be wrong to simply dismiss the West Indians’ contributions and the efforts they and other immigrant groups made to assimilate. To what degree, if any, did assimilation/integration succeed? The degree of integration that was accomplished can arguably be chalked up, not only to the progressive zeitgeist of those decades, but also to Britain’s imperial legacy: to the cultural ties forged and the prestige the nation continued to enjoy later, in the fading afterglow of Empire.

In economic and social terms the integration of black people of Caribbean origin was largely a failure

By and large, those West Indians who arrived on the Windrush and settled in London, Birmingham, Manchester, Liverpool and a number of other cities appear to have been sincere in their determination to make an honest living in Britain and to assimilate. But their good intentions and hard work yielded diminishing returns over subsequent generations. Granted, West Indians’ cultural contribution can’t be denied. Their musicians had an especially outsized impact, enlivening the British jazz scene during its heyday in the 50s and 60s and later introducing reggae, ska and dub to the country. Perhaps the best advert for Caribbean integration were multiracial ska purveyors The Specials — the biggest chart-toppers on the wittily named 2 Tone label.

The West Indians also made, and continue to make, major contributions to boxing, cricket, athletics and other sports. Frank Bruno – born of Windrush generation parents – won the European and World Boxing Council heavyweight titles and became a hugely popular media personality and mental health campaigner. But in economic and social terms the integration of black people of Caribbean origin was largely a failure. Rudy clearly did not get the message as by the 1980s 20-25 per cent of West Indians of working age were unemployed (several times the UK average) and in some areas nearly half of West Indian households were in social housing. They were also overrepresented in crime statistics.

I don’t believe assimilation/integration was always doomed to fail. It may well have achieved some measure of success had ways been found to check Britain’s decline and preserve British moral authority, the authority of the British state in particular. But the white heat of Wilson’s technological revolution couldn’t do that; nor did Thatcher pull it off by rolling back the frontiers of a supposedly bloated and inefficient state. Blair had faith in education, education, education, but his policies — many of them now widely hated –– failed to reverse the decay of British society and if anything hastened it. The wider West, too, has lost much prestige and moral authority over the past half century. The reasons being numerous and complex, I won’t try to do them justice here, but bad policy, military failure and economic and cultural decline are among them.

One book that throws light on this subject is Eric Hobsbawm’s The Age of Extremes 1914-1991: the Short Twentieth Century. Hobsbawm devotes the last third of the volume to what he calls “the Landslide”, a period, beginning around 1973 (the year US withdrew troops from Vietnam and OPEC quadrupled oil prices), when the world “lost its bearings and slid into instability and crisis”. This period saw the appearance of the first signs that universalism — at least the Enlightenment variety espoused by both the West and the USSR — might be in trouble. 1979’s Iranian Revolution saw the rival universalist ideology of Islamism make a dramatic entrance onto the world stage. This movement’s expansion in the years following led to the rejection of Western and Marxist models of development in many Muslim countries. Further east, the death of Mao in 1976 occasioned a change of direction in China, away from Marxist universalism. Under Deng Xiaoping the country instituted market reforms, embracing a limited capitalism. These changes were accompanied by a shift in official rhetoric, away from the ideals of Maoist revolution and towards those of a modern Han nationalism.

A highly significant development within the West at this time was the rise of French postmodernist thought — the theories of Foucault, Derrida, Lyotard and others — to a position of dominance in academia. Deploying a Nietzschean perspectivism, these thinkers undermined the truth claims on which both liberal and Marxist universalism were based, while also condemning as oppressive not only universal ideals but even the very notion of progress. The discourse of multiculturalism owes much to their postmodern critique.

Despite these developments, the universalist aspirations of the US-led West and, to a lesser extent, the Soviet Union, still possessed some credibility in the 1980s. But in retrospect it seems likely the idea of a universal civilisation had already lost much of the power it had formerly held. Though the surprise collapse of Communism from 1989–1991 left the West’s specific brand of universalism, defined by capitalism and liberal democracy, apparently triumphant, the humiliation of 9/11 and the ill-fated attempts at nation building it led to in Afghanistan and Iraq showed how misplaced the restored confidence of the 1990s had been. The ideals of Western liberal democracy also failed to take root in post-Soviet Russia, which followed the course Emil Cioran had foreseen half a century before in an essay entitled “Russia and the Virus of Liberty” (collected in 1960’s History and Utopia). Writing in French, the Romanian thinker predicted that, although “in some sense” Marxism would have alienated Russia from her roots, “after a forced cure of universalism, she will re-Russify, in favor of Orthodoxy.”

By the late 1990s, that other farsighted Francophone gadfly, Jean Baudrillard, was convinced the West’s own universalist ideals were heading the way of the dodo. This is from interview book Paroxysm (1998):

… what has triumphed isn’t capitalism but the global [defined by J.B. as “the globalization of technologies, the market, tourism, information”], and the price paid has been the disappearance of the universal in terms of a value system. We are, admittedly, seeing a kind of excrescence of human rights and democracy, but only in so far as their efficacy has long since disappeared…. Globalization seems irreversible; the universal might be said, rather, to be on its way out.

In Britain, assimilation was an unrealistic ideal, but multiculturalism has proven to be a fatally weak one

This diagnosis has arguably been borne out, not only by events, but also by the transformation of discourse that has taken place in this century. No one now equates modernisation with Westernisation, and few hold to Fukuyama’s belief that the royal road of progress should eventually lead to liberal democracy. Left-liberals won’t even suggest that as an ideal, no doubt aware they’d be “called out” for racism and Islamophobia.

In Britain, assimilation was an unrealistic ideal, but multiculturalism has proven to be a fatally weak one. The accelerated decline it has brought about is destroying whatever moral authority the British state has left. Perhaps the ideal of integration would have yielded better results if British society, our governing class in particular, had had the persistence and self-belief to stick with it. It may well have been of considerable help had they, and we, taken a broadly positive stance on our imperial legacy, instead of demonising it in the name of a finally unworkable universalism and thereby fomenting racial grievance. But this is all now a matter for historical speculation. The conditions of the immediate postwar decades are long gone. Now, the question is how to restore order and a measure of optimism in Britain, amid the wreckage of the multicultural project.