Just before dawn, in a concrete yard inside an Iranian prison, the condemned is led out with his hands tied behind his back.

A coarse cloth hood is pulled over his head. A noose is slipped around his neck and cinched tight beneath the jaw. There is little ceremony.

Sometimes he is suspended from a beam, sometimes from the arm of a construction crane. A stool is kicked away, a trapdoor released or the crane begins to rise. His body drops.

Death often comes slowly: not with a clean snap of the neck or spine, but by strangulation. He convulses. His legs kick involuntarily. His chest heaves as the airway collapses.

In some cases – as former prisoners and defectors have described – the executioner or a guard pulls down on the legs to hasten the end.

After several minutes, a doctor checks for a pulse. If done in public, the body is often left dangling for a while, a warning to others.

This is how the Islamic Republic of Iran dispenses ‘justice’.

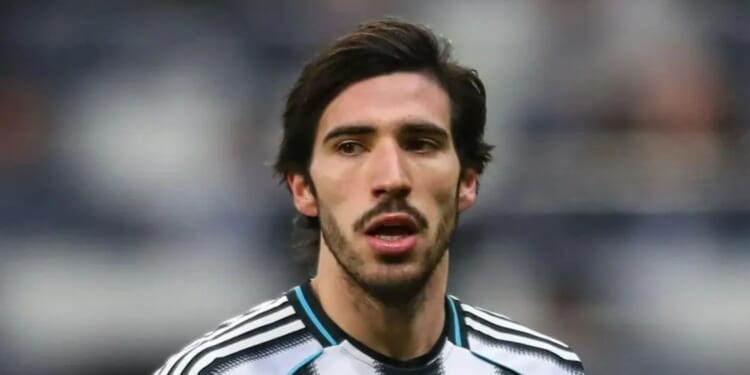

In past days, the name Erfan Soltani has emerged as that of the latest young Iranian protester rushed through the mullahs’ industrial machinery of death.

Erfan Soltani was charged with moharebeh (‘waging war against God’), which carries the death penalty and, in its medieval absurdity, tells you all you need to know about the Islamic Republic

Arrested in the protests now sweeping the country, tried in a revolutionary court and denied meaningful access to a lawyer, Soltani’s case has moved with terrifying speed.

He was charged with moharebeh (‘waging war against God’), which carries the death penalty and, in its medieval absurdity, tells you all you need to know about the Islamic Republic. He is the first known protester to face execution in the current wave of demonstrations but unlikely to be the last.

From detention to Death Row in days. The regime is no longer content to imprison and beat protesters – or to blind them, which is a particular favourite. It is now reminding the country, the world and, most of all, its own people that if you rise up for freedom, the rope awaits.

Almost as bad is the sordid ritual that surrounds it. Families are called in at the last minute; given almost no time with their son or daughter.

Members of Soltani’s family were reported to be heading to the Ghezel Hesar prison to see him late on Tuesday night, but sometimes families are informed only after the burial – often in an unmarked grave.

In ordinary criminal cases, the process can take years. In political cases, especially in moments of crisis for the regime like this, the process is accelerated – with deliberate cruelty.

Revolutionary courts, never scrupulous, dispense with normal ‘standards’ of evidence. Thugs extract ‘confessions’ under torture. The state then broadcasts these on television. Appeals are cursory or meaningless.

In Iran the law is a state weapon, speed a part of the punishment.

And why not? There are few checks and balances to restrain them when their blood lust is up.

The head of Iran’s judiciary himself, Gholamhossein Mohseni-Ejei, invented the trumped up charges demonstrators now face when he said yesterday: ‘If a person burned someone, beheaded someone and set them on fire, then we must do our work quickly.’

This is the context in which Soltani’s case must be understood, no matter that President Trump has warned Iran that the hanging of protesters is a ‘red line’ that must not be crossed.

It is no isolated act of judicial savagery. It is a signal – and a clear one. But, perhaps, not the signal the regime thinks it is.

As someone who has studied authoritarian systems, it is clear to me that when a regime is secure, it can afford not to hurry. It can afford at least the display of due process, fairness before the law and even a strategic measure of mercy.

When it is insecure it reaches for the most absolute instrument it possesses: mass execution.

The promiscuous use of the gallows is not the language of strength but of desperation. Nowhere is this clearer than with the Islamic Republic. Hanging has always been integral to its practice of governance and display of power.

From the earliest days after the 1979 revolution, when opponents of Ayatollah Khomeini were strung up in public squares to the routine pre-dawn killings in prisons today, the noose has been among the state’s most favoured method of expression.

The mullahs’ regime was baptised amid a melee of vengeance: in its first two years alone, sources report that revolutionary courts sent roughly 3,000 to 5,000 people to their deaths, including former ministers, generals, intelligence officers, judges and political rivals.

The head of Iran’s judiciary, Gholamhossein Mohseni-Ejei, invented the trumped up charges demonstrators now face

As the regime consolidated its rule and the Iran-Iraq war raged, the killing deepened: between 1981 and 1988 it’s likely that around another 10,000 political prisoners were executed or disappeared.

Then came the 1988 prison massacres, when some 4,000 to 5,000 supporters of a rebel group – the People’s Mujahedin Organisation of Iran (MeK) which advocated democracy and women’s rights – were hanged in a matter of months, quietly and industrially.

In its first decade the Islamic Republic is estimated to have put 15,000 to 20,000 of its own citizens to death, not the mark of a revolution secure in its legitimacy but of one that, from pretty much its outset, has been condemned to rule by terror.

Today, the context is different. The Islamic Republic is not a young system imposing itself on a nation. It is an ageing and reviled theocracy confronting a society that has long ceased to believe in it.

The young loathe its ideology. The business classes no longer trust its economic management. The country’s women have long had enough.

After the 2022 uprising that followed the death in prison of 22-year-old Iranian Kurd Mahsa Amini – who was tortured and beaten for not wearing her hijab correctly – around a dozen were executed.

Protesters were executed after the 2022 uprising that followed the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini – who was tortured and beaten in prison for not wearing her hijab correctly

The protests grew – once again, yet more of the regime’s legitimacy dribbled away. But when legitimacy evaporates, terror must work all the harder.

It’s all part of the state’s broader drive to embed its violence within social and religious practices, turning death into a spectacle of perverted authority.

In so-called ‘retribution’ cases where the family of a murder victim is permitted under Iranian law either to pardon the accused or to insist on execution, the ritual can become even more brutal with relatives sometimes personally kicking away the stool the condemned is standing on.

There’s no doubt a growing list of protesters and dissidents are to face the same fate as Soltani. The charges will be similar: ‘enmity against God’ will be joined by the equally sinister fasad-fil-arz (‘corruption on Earth’). The evidence will be laughable, the trials swift, the outcomes final. Families will be warned not to speak out.

The logic is clear. The regime hopes that fear of the rope will succeed where its propaganda has failed.

It hopes that the knowledge that a protest can lead, not merely to prison but to a noose, will empty the streets

But it is wrong. Erfan Soltani’s imminent hanging will only reaffirm what Iranians already know: this is a desperate and dying revolutionary state that they must oppose with everything they have.