Two current yet contrasting exhibitions of the work of one of the greatest sculptors of the twentieth century, Alberto Giacometti, have much to say about the violence of that century and the violence yet to come in our own, as the post-1945 world breaks apart.

The Encounters exhibition at the Barbican Centre has contemporary sculptor Mona Hatoum responding to Giacometti’s work. Hatoum is the second artist to respond to the Giacometti pieces the Barbican has on loan in its sunlit second floor space.

They are disquieting exhibitions for disquieting times

Deep in the foundations of the Tate Modern’s Blavatnik Building in the dark circular spaces previously used to store oil when the gallery was a power station, there is another small but evocative exhibition. The space known as The Tanks has on display several of Giacometti’s later works, made after the Second World War.

Both exhibitions explore the psychological and physical impacts of war. They are disquieting exhibitions for disquieting times.

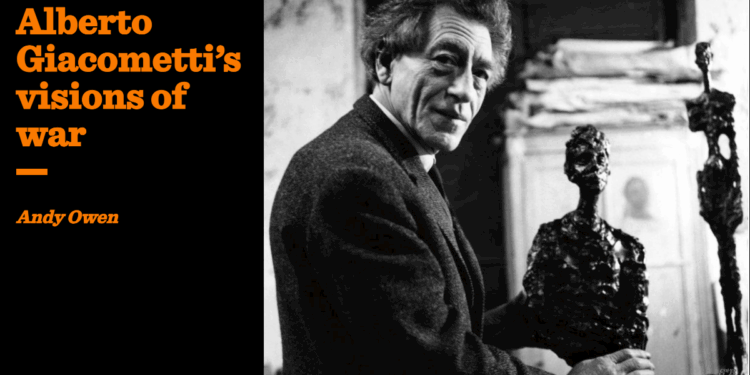

Giacometti was born in a remote Swiss valley in 1901, the son of a successful Swiss painter. He made his first sculpture of his brother Diego at just thirteen years old. British sculptor Anthony Gormley describes him as, “this man who comes from a mountain, arrives in Paris and has this simply insatiable appetite for the possibility of sculpture”. Arriving in the French capital in 1922 he discovered surrealism. By 1931, Giacometti began to participate in some of his friend André Breton’s surrealist group’s activities. He devoted himself to capturing dreamlike visions. Giacometti said that when making sculptures during this period he reproduced images that were “complete in my mind’s eye … without stopping to ask myself what they might mean.”

The themes of this decade are sex and trauma and are epitomised by the Woman With Her Throat Cut (1932) on display at the Barbican. Spread out on the floor as you enter the exhibition it takes a moment to understand. Our brains are programmed to recognise human faces and figures with ease, we struggle to recognise our kin after the dehumanising impact of violence, when features, pieces and parts are not where we expect them to be. The obscurity is heightened by the surrealist flourishes that suggest that the woman, whose spine is bent in pain while her pelvis is thrust forward, is part arthropod.

Next to it is Hatoum’s A Bigger Splash, a series of six deep red glass sculptures also on the gallery floor. There is no body here but violence is suggested by the colour of blood and the resemblance with the impact splashes of bullets or shrapnel hitting the dirt.

As war was about to intervene in all their lives, Giacometti left the style of the surrealists behind, disappointing Breton by returning to “realist” work with models, although he would continue to engage with their dark themes for the rest of his life.

Giacometti returned to Switzerland. There he met Annette Arm, who would become his wife and model. Living in a hotel with her in Geneva as war raged across Europe, his art shrank. He sculpted smaller and smaller figures, many reduced to the size of a finger. Like being caught in a storm at sea, war quickly dispels any notion that you have control over your own life. It exposes the true scale of our agency.

Following the war, Giacometti returned to Paris. While there he experienced a shattering of his perceived reality that has some similarities with the experience of Roquentin, hero of existentialist novel Nausea, written by Giacometti’s friend John Paul Sartre. Roquetin, when confronting the knotty root of a horse chestnut tree, has the nausea-inducing perception of the raw, naked, meaningless of its existence. Giacometti, coming out of a cinema on the Boulevard Montparnasse, experienced a “complete transformation of reality” and understood that, up until then, his vision of the world had been photographic, but in truth “reality was poles apart from the supposed objectivity of a film.” Feeling as if he was emerging into the world for the first time, he trembled in terror as he observed the heads around him, which appeared isolated from space. Entering a familiar cafe he experienced time freezing and encountered the head of a waiter as a sculptural presence as he approached him, “his eyes fixed in an absolute immobility.” The Tate exhibition includes two busts of his brother Diego and wife Annette, all three have intense, defiant gazes.

He began to focus on elongated single figures, often walking or standing, as well as figural groupings in different spatial situations (the equally spaced petite figures mounted on a high pedestal of Four Figurines on a Pedestal, inspired by seeing four sex workers across a room, is silhouetted against St Giles’ Church across from the Barbican). As his figures gained height they lost weight, whittled down to heavily worked but twig-thin figures. New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art described his figures as evoking “lone trees in winter that have lost their foliage.” His expressive figures became associated with a sense of post-war trauma.

One of his most well known pieces for this period is on display in the Tate. Sculptured in one night in 1947, Man Pointing Bronze was described by Sartre as always halfway between nothingness and being. Emerging from the dark nothingness of the tanks the spotlit pointing man feels accusatory — pointing at what we have done to each other from the Holocaust to Hiroshima. The shadows that connect his figures here to the darkness filled space, call to mind the shadows left on buildings after the atomic bombs while also dwarfing the sculptures themselves. We are drawn to their impact rather than the art itself.

When focusing on the sculptures themselves, Giacometti’s constant reworking leaves them looking, scarred and mutilated or even charred like blackened embers when spot lit as they are. There’s a sense with many of his pieces that, with just a bit more cutting away, they might fragment and fracture. According to Giacometti, “it is in their frailty that my sculptures are likenesses.” After years of conflict that gave us new terms such as “genocide” and “crimes against humanity,” what we could be united in is our exhaustion, appreciation of the fragility of our existence and the guilt of perpetrators and survivors alike.

These elongated sculptures brought him fame and money. He drank in cafes with Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, and went for late night walks with playwright Samuel Beckett. He continued to endlessly rework and repeat the same figures in plaster. It was the nature of the material that a sculpture was never finished. It seems apt then that his art is still inspiring encounters today, its work not yet complete.

According to Hartoum, her encounter with Giacometti deals with themes of conflict and displacement, distilling the physical and mental impacts of war into sculpture. The works in the Barbican are inspired by a variety of conflicts but which ones are not always obvious. They are stripped of the specific politics and focus on the impacts. Hatoum’s work has responded to Hiroshima, and conflicts in Lebanon and Palestine. Her 4 Rugs (made in Egypt) is a small version of a work comprising twelve rugs for the 1998 Cairo Biennale responding to the 1997 massacre of 58 tourists and 4 Egyptians by terrorists in Luxor at the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut. Hatoum dropped an articulated skeleton on the floor and recorded the positions in which it fell on the rugs. The result is a series of poses suggesting violent or unexpected death — not placed neatly in a coffin.

The exhibition shows the impact of war when it evades places where we are meant to feel comfortable and safe. It shows the impact on domestic scenes in homes, on an infant’s cot, on hospitals, and ultimately on bodies. These are scenes that are stripped of comfort. Hard materials and straight lines replace softness and curves. In Incommunicado the cot’s springs are replaced by taunt cheese wire, in Divide a hospital screen has its curtain replaced by a grid of barbed wire and in Interior Landscape, one of the few pieces to explicitly reference a particular conflict with its inclusion of maps of Palestine, the bed is all steel and wire. Emphasizing this a display cabinet contains natural images that contrast with those industrially produced: photos of the wriggling lines of rivers from, a colon, the artist’s hair, a brain and a scrotum that contains the potential of life.

In Remains of the Day, Hatoum presents a domestic scene that has been obliterated by violence. Carbonised fragments of wood are held together by wire, resembling the ghostly remains of a family dinner table and a child’s toy. Inspired by the atomic bomb it could equally represent a scene today in Gaza or Kyiv after a missile or drone attack.

Her sculpture Round and round — a ring of toy soldiers all stabbing the next in the back — makes clear the unending and self-aggravating cycles of violence that drive so many conflicts of the past into today.

Hatoum routinely uses display cases in her work. Here, she creates a cabinet inspired by a wardrobe in Giacometti’s studio she saw in an archival photograph. Hatoum has created three new works for this exhibition, all of which are contained in the cabinet and allude to a damaged body: a cage imprisoning a red glass blob resembling human organs; a glass tile with a relief of a disembodied child’s arm; and a clay work with nails, suggesting both figures in a landscape and a tool of violence. The cabinet also contains Giacometti’s The Cat. The elongated, tightly wound, feline made me think of the unfeeling predatory autonomous robotics of future wars.

For those who had lived through the industrialised slaughter of the twentieth century wars Giacometti’s sculptures would have had specific meaning and elicited deeply personal responses from memories and emotions now gone, passed away with those who once held them. I look at these sculptures through the lens of the conflicts I witnessed. “Iraq” and “Afghanistan” sound in my mind as I wander through the galleries, words that no longer represent the places and the lives of those living there today, but are a short hand for a set of experiences temporary visitors inflicted on others and had inflicted on them half a lifetime ago. Others will be reminded of totally different conflicts. It highlights the universalism of war’s impact on the individual.

War is the most exhilarating, timeless human failure. Part of the exhilaration of being in war is the feeling that you are at the centre of things, where history is being made. But history rolls on, and your war moves to the periphery, out of the spotlight. It moves into the darkness of national consciousness. It may later be mined for material to justify new wars or even a reason not to fight, but when this happens there is no guarantee the descriptions of it will be recognisable to those who were there. Or it will just be forgotten, that time and place so important to you becomes meaningless to others. Long after everyone has forgotten the specific politics of the conflicts, these pieces show what the soldiers and civilians who were there are left with: the images of trauma, the sense that the everyday can be punctured by tragedy at any moment and that guilt. This, that which remains, is what Giacometti and Hatoum capture.

Creating art is the antithesis of making war, even when the former explores the impact of the latter

The Barbican exhibition ends with Hot Spot, Hatoum’s well-known red neon globe, which is inspired by her idea that modern conflicts are now no longer restricted to certain areas of disputed borders. As we welcome in the new year some of the hotspots that inspired the art here will continue to burn. There will be new wars too as we move through a violent transition from a rules based international order to a system of geopolitical spheres of influence. In the new system, regional powers will become increasingly belligerent, trampling established international laws and norms to assert themselves. In geopolitics, “might” is increasingly meaning “right.” This “might” will invade spaces once felt as safe and harm the bodies of many thousands as conflict seeps around our glowing globe.

Creating art is the antithesis of making war, even when the former explores the impact of the latter. Art can show us that in another context fragility can be seen as beauty, and it is our frailty that gives us our likenesses. Art can attempt to soften the hard edges of war, showing us our fate and finding beauty within its tragedy, but it won’t one day lead us to a perpetual peace. We are creatures driven equally by both creation and destruction. The hard edges will return, as, like Hatoum’s toy soldiers, the cycle goes round and round without end.

Hatoum’s Encounter with Giacometti will be followed by American artist Lynda Benglis in February. The Alberto Giacometti exhibition in The Tanks at the Tate Modern is on until May.