We can thank the London Fire brigade for sending our last family Christmas off with a bang.

I’d been divorced from my husband, celebrity tailor Doug Hayward, for more than 30 years and we’d barely exchanged a polite word in that time.

Yet now he was in the last, tragic stages of dementia, we decided to make a go of one final celebration – and I’m so glad we did.

Although the memories are laden with inevitable sadness, there were many endearing moments, too, which other families struggling with this burden might well recognise.

On Christmas Eve, I got back to my central London flat accompanied by my daughter and Doug only to find the place filled with noxious smoke and fumes. I dialled 999 and, within minutes, six fire engines had screeched to a halt outside, terrifying the neighbours.

At least 20 keen young firemen were soon swarming over the flat, tracing the problem to a small, seldom-used wine fridge in the living room, which had mysteriously exploded.

Did it spoil the festive mood? Not a bit. The firemen were so absurdly fit under their flimsy T-shirts, despite the winter weather, we expected them to break into a chorus of YMCA.

‘Oh, how wonderful,’ exclaimed the ex. ‘They’ve all come for Christmas. It’s just like the old days.’

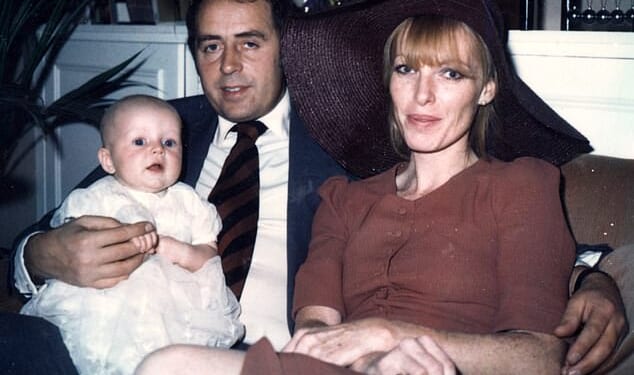

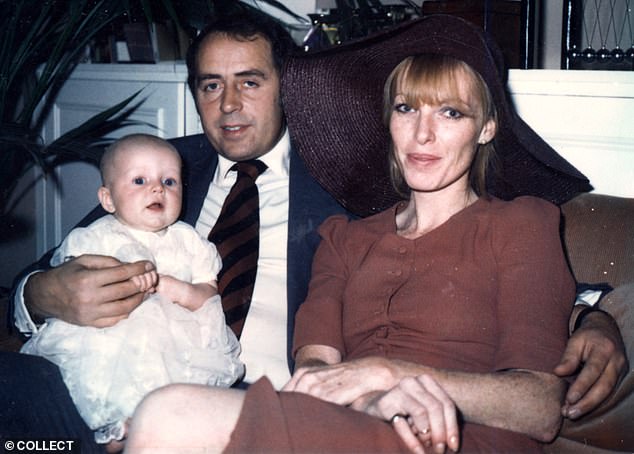

Glenys Roberts with her then husband Doug Hayward and daughter Polly

The old days had been pretty special. Doug, who dressed many a star including Roger Moore, Clint Eastwood and the Queen’s photographer cousin Patrick Lichfield, was a great raconteur who thrived on company.

In the run up to Christmas, we always had a full house, which might include any one of his celebrity friends.

Doug had been hysterically funny in public, yet not always in private. As things fell apart, I would have every right to resent our bitter breakup.

But now, seeing my former husband at his most heartbreakingly vulnerable, it was a different matter. It seemed doubly, trebly unfair such a cruel fate – a diagnosis of dementia in his sixties – should lie in wait for a man who had once been such a dynamic personality.

I only know that, in these last days, I began to find his peccadillos charming. It was obviously the same for him.

As he said when we re-opened relations to help him through the final months of his illness: ‘Forget the past. All is forgiven. It’s the future that counts.’ My terminally sick, eternally positive ex was actually contemplating a future.

At this point, Doug was seriously dependent on outside help – given to lighting his bedclothes with matches, mistaking them for the gas fire, and breaking eggs onto the hob rather than into a pan.

While he was frustrated with the limited vocabulary that now remained, it led to an enchanting turn of phrase. He called his house key ‘the moon’ because it reflected the streetlight.

He won’t mind me telling you all this, particularly not if it rings a bell with other families trying to make the best of this dreadful condition during the festive season. Who wouldn’t have tried to ease his plight? He was the father of our much-loved daughter, after all.

So, despite holding down a demanding job as a writer for this newspaper, I plunged in.

I have long wondered why so many counselled me against getting involved. My conclusion is that dementia either embarrasses or scares the life out of them. My own doctor was the worst: ‘You don’t have to do this,’ he said, ‘you’ll destroy your own health.’ The runner-up was Gloria Allred, the feminist lawyer famous for fighting on behalf of Epstein victims. I’d known her from working visits to California.

‘You shouldn’t be at his beck and call,’ she insisted. ‘It’s a betrayal of the sisterhood.’

The staff in Doug’s famous Mayfair shop resented me. His friends were lukewarm, too, including Joan Collins and Michael Caine

Only one, club owner Mark Birley, who wasn’t well himself, really stayed the course. Doug and Mark lunched together every day in Birley’s club, George, where the two men, both now in states of serious decline, sat at their favourite table and talked gibberish.

Yet, when Doug begged me to take him to Birley’s funeral, none of his famous friends could bring themselves to say hello except the ex-Duchess of York, Fergie.

Leaping across the pews she took Doug in her arms and hugged him tight. Whatever she has done to fall out of favour, I will always remember that genuine act of kindness.

Many supposed friends thought Doug should be in a home, out of sight and out of mind, but we decided to carry on as usual – and as long as we could. There were times when we might as well have been cantankerous marriage partners still. Take the plundering of the supermarket shelves.

‘Put that back Doug. You don’t like eggnog.’

‘Yes, I do.’

‘No, you don’t.’

It had been the favourite of his long-dead mother and was duly put in the trolley – only to be taken out at the till while we distracted him with his favourite Maltesers.

Undeterred, Doug moved on to a chorus of, ‘Have you got the bread sauce? You’ve forgotten the parsnips. Christmas has to be done properly, it’s traditional.’

He was the tailor renowned for being able to make anyone look the perfect English gentleman. So, yes, our Christmases were traditional.

My daughter and I always bought the biggest tree we could fit diagonally into my Mini with the ends poking out of the windows.

This last Christmas was no different. For the first time since our separation, Doug came to the flat we had once shared, took one look at the decorations and said, ‘You’ve made it into a proper home.’

From a man who divorced me for my lack of domesticity, this was a compliment to cherish.

In the old days, Doug had insisted on an annual showing of Lawrence of Arabia, starring Peter O’Toole. But this time we just lingered at the table, my newly married daughter, son-in-law and I, while Doug chastised me for forgetting the bread sauce – which I had indeed forgotten once again.

‘You do it on purpose,’ he said, ‘And where are the chipolatas?’

Oh, damn those chipolatas! I’d been forgetting them since 1969.

It was all heartbreakingly normal until, suddenly, he missed his carer, who had taken a rare day off. Gone was the veneer of goodwill. At one point we thought he was going to break the place up.

‘Keep your nerve and play it by ear,’ was the constant advice of his geriatrician and, aided by a dose of the anti-psychotic drug haloperidol, somehow we did.

That Christmas was touch-and-go, yet we survived – and I wouldn’t have changed a thing.

It was all so deliciously predictable, even down to Doug refusing to eat the Boxing Day bubble and squeak. Yet, we learned a great deal, particularly that you never stop caring for someone, however damaged they are – and that we would rather have had him around in any state than not at all.

Doug was up for one more outing before we had to part company for ever. On New Year’s Eve, we booked our usual table at Scott’s restaurant in Mayfair and celebrated what should have been our 38th wedding anniversary.

It went rather well and we were still by no means ready to say goodbye when, four months later, in the spring of 2008, the bell finally tolled for my stricken ex at the far-too-tender age of 73.

I’m so glad we managed to give Doug one last family Christmas. We had loved each other, we had hated each other. And, oh, how I wish he were around this year, too.