On a shuddering December night, the Old Lady of Lime Street looms up towards the low clouds over Liverpool like an ocean liner, a stranded ship of white stone and dark windows.

I climb the steps, push through the antique revolving door and enter the wild dilapidation and haunted grandeur that is the Adelphi Hotel.

The most charismatic hotel in Britain is also, according to hundreds of travellers, easily the most awful and the most ghost-ridden. Working in the city and living far away, it was for a time my weekly base. I came to love its eccentricities – and to dread its desperate spirits.

On nights like this it exists in an older time. The herring gulls which live on the hotel roof turn and wheel in the winter darkness, lit from below by streetlights, laughing and crying.

The receptionist hands over a key to a room on the notorious third floor – the floor I have learned is riddled with stories of encounters with the uncanny.

One of the lifts is out and the other is up to its usual tricks. They say ‘The Whistler’ haunts these lifts – a spirit which breathes down the back of your neck and occasionally taps guests on the shoulder.

I recall, too, that in 1961, the hotel’s bell boy, Raymond Brown, 15, died in the luggage elevator. His ghost reportedly stalks the hotel to this day, offering to help with baggage.

Seeking my room along the cavernous corridors is a disturbing business. Echoes of riotous nights gone by combine with snatches of conversation, spiralling laughter, cries of passion, angry disputes and blurts of TV.

Residents of these rooms have reported waking to find a shadowy figure standing by the bed. A pickpocket also supposedly haunts this floor. You wake to see a human shape rifling through your clothes – she looks like a young woman, they say – but when you cry out, she vanishes into thin air.

The most charismatic hotel in Britain, the Adelphi Hotel, is also, according to hundreds of travellers, easily the most awful and the most ghost-ridden

Antique time and restless energies swirl through eavesdropping silences. You feel watched and accompanied, with that sense of something beside you

Antique time and restless energies swirl through eavesdropping silences. You feel watched and accompanied, with that sense of something beside you which makes you glance over your shoulder.

My room is somewhere at the back of the hotel. Last winter, another traveller reported seeing a chandelier in one of these passages swinging – by itself. ‘Hurry on!’ I think. ‘Get to the room and shut the door.’ The lock clicks and the door opens. But when I turn on the light there is a kind of lurch in the air, as though I have interrupted something.

As a travel writer, I have worked and journeyed in more than 50 countries and stayed in many strange places. Bugs, bats, snakes, thieves, insects, lunatics, spiders and conmen are all in a night’s work – all I ask for are clean sheets and a lock on the door, and I do not do ghosts.

But I hesitate, now. It is a large room; one of the old ones with a high ceiling and dingy drapes. I take three steps forward and my breath catches. As the door closes behind me the dim space prickles with an awful feeling, as though the whole room is filled with a frigid stillness – something malevolent and horribly present.

In flashes of thought I try to imagine spending the night here. I will hunch under the covers. I will face the door.

But there is a dreadful anticipation in the mere idea of it: that feeling of something at your back, something there, something you cannot shut your eyes to because you fear to wake and see it.

I try to dispel the notion. My philosophy of ghosts is that you don’t see them if you don’t want to. I have a way of warding them off. ‘Hello room!’ I say. ‘No ghosts, please.’

The sound of my voice makes the silence worse. The air itself seems to bristle and the feeling now is quite terrifying. I have never known anything like this atmosphere of absolute hostility.

A reek of dankness overcomes me. There is something horribly near and watchful here. I grab my bag, turn and flee as the door bangs angrily behind me. I speed back along the corridor to the lifts.

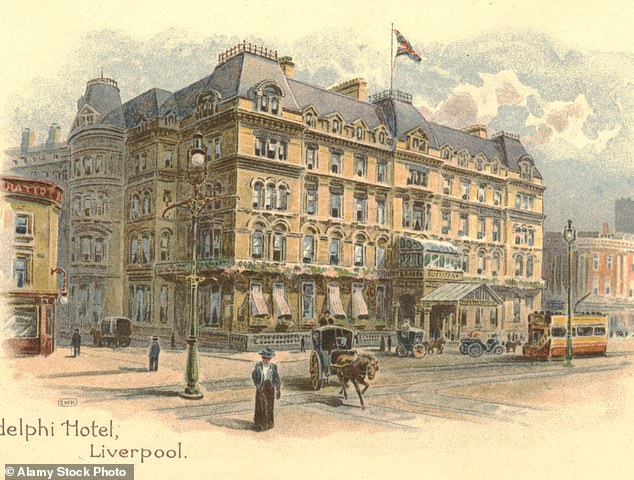

The Adelphi opened in 1914, the third hotel to occupy the site since 1826. It has a soaring Grand Court, with its pilasters and chandeliers, while the Hypostyle Hall’s ionic columns, huge corridors and high-ceilinged bedrooms, were all designed with Edwardian dash in the Empire style by architect R. Frank Atkinson.

I wish I could have asked him about the weird mezzanine floor I once came across, discovered half-hidden somewhere in the back of the hotel, with a spy window looking down into the palatial hall. In another corner of the building, I stumbled into a Freemasons’ Lodge, all high oak panelling, secret vows and rituals.

There is no end to the secrets, legends and stories of this hotel. In the early 20th century, when it hosted wealthy passengers of the Atlantic liners travelling from

Liverpool to America, its basements accommodated tanks of live turtles destined for turtle soup.

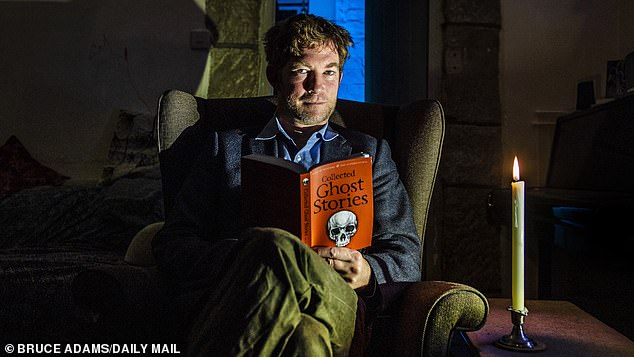

Horatio Clare, who called the Adelphi his weekly base for a while. ‘I came to love its eccentricities – and to dread its desperate spirits’

Harry Haycock, a former night porter, once described Grand National nights when the hotel was packed out.

‘For many years two parties used to get the big ten-foot tables and use them as toboggans down the two staircases, and there used to be a bookmaker at the bottom taking bets on which load of people would win,’ he recalled.

Part of the attraction of the Adelphi is its power to travel in time. You can feel it as soon as you cross the threshold and the tales of past guests come to life.

Winston Churchill holds meetings upstairs, Franklin Roosevelt had lunch earlier, Bob Dylan signs autographs in the lobby, that uproar is Cilla Black’s wedding in the ballroom, and the horse signing the register with a pencil between its teeth is Roy Rogers’ steed, Trigger.

Charles Dickens dashes by en route to the docks to board the RMS Britannia to America. Dickens will be horribly seasick on his crossing – and the Adelphi has hard times ahead, too. The bleakest days arrive at the hands of the present owners, the ironically named Britannia chain.

Rated the nation’s worst hoteliers 11 years in a row by Which?, Britannia Hotels has been roundly damned for the current state of the place. The local MP, Kim Johnson, calls today’s Adelphi ‘a blight on Liverpool’ and wants Britannia to ‘move on’.

Reading the hotel’s reviews is an adventure in itself. Recent guests describe mould in the bathrooms, water dripping from ceilings, wires hanging from walls, string in the bed, sticky carpets, razor blades in the bathroom, bloody handprints on walls, corridor drunks, in-room karaoke, boiling radiators, freezing windows, gusts of skunk smoke and harassment from people demanding money and cigarettes at the main door, who turn out to be other guests.

In the lobby, celebrated Liverpool writer Jeff Young once watched an outraged guest approach the receptionists’ counter. ‘I’ve just been mugged on the fourth floor!’ he wailed. ‘Not again…’ groaned the receptionist.

But for the eccentric, the atmospheric – and the haunted – I believe there is nowhere to touch it.

Enthusiasts of the paranormal scour the place with recording equipment, to the spirits’ chagrin.

A postcard of the Adelphi, which opened in 1914, the third hotel to occupy the site since 1826

Residents of these rooms have reported waking to find a shadowy figure standing by the bed. A pickpocket also supposedly haunts the third floor

Rotherham-based ghost hunters Lee and Linzi Steer claim they were called ‘b******s’ on one ghostly recording, while Jessica Sims and Ellie-May Ramsey, YouTubers from the Isle of Man, reported being advised, ‘Don’t try it’ by something which did not want to be recorded by ‘silly girls’, as the disembodied voice put it.

A guest who stayed on the third floor back in February with her daughter wrote in a review: ‘The room and floor had an oppressive feel. The night was horrendous, I just wanted it to be over. Weird noises in the night, strange growl-like sounds and eerie laughing.

‘Barely slept a wink and was praying for morning to come round. Lots of banging and doors opening on their own. Don’t like thinking about it to be honest.’

In 2015, among the audience for local paranormal writer and expert Tom Slemen’s talk in the Sefton Suite, modelled on the smoking lounge of the Titanic, there appeared three figures in full naval uniform.

‘There were gasps of shock when this trinity of ghosts vanished,’ Slemen later told reporters.

Many of the Adelphi’s rooms are wide spaces where marble mantlepieces preside over assemblies of furniture from another age, where you could imagine sitting and conversing with an apparition.

Your bathroom might contain a huge 1930s cast-iron bath with a mighty faucet and a clanking mechanical draining mechanism.

Steaming in a bath the size of a turtle tank, you hope you will not encounter George, a forlorn figure with a toothbrush moustache who took his own life here in the 1930s, since when he has occasionally waved from a hotel window at passers-by on Liverpool’s busy streets below.

Another December night in 1942 saw the end of another desperate man. Sir Henry ‘Jock’ Delves Broughton was in exile from Kenya, where he had been acquitted of the murder of his wife’s lover, Josslyn Hay, Earl of Erroll.

While the law was unconvinced of his guilt, his ‘Happy Valley set’ – a notorious society of racy aristocratic colonials whose decadent lives were immortalised in the film White Mischief – believed him guilty and ostracised him. His famously beautiful and promiscuous wife, Diana Caldwell, had moved on.

The whole world, he must have felt, knew him for a cuckold and believed him a killer, which subsequent findings suggest he was.

Shortly after arriving in Britain, Delves Broughton checked into the Adelphi, cast his last glances around his room and ended his life with a morphine overdose.

He numbers among a mournful legion of souls who have died here. In 2006 Madhav Cherukuri, 25, drowned in the hotel pool, which was subsequently closed.

In 2022 Chloe Haynes, 21, died tragically, crushed by a falling wardrobe. Last year Gary Wrest, 25, recently released from prison, took his own life in his room.

All the great hotels see their share of death and tragedy. They are wells of souls in the hearts of their cities – the overnight homes of the joyfully in love, the determinedly on business, the delightedly on holiday, the questing, the fleeing, the haunted, the hoping, the anguished and the regretful. In my Adelphi years I was all of these, too.

Most of the buildings’ stories are told in private, when the room doors shut, but the structure holds the echoes of all it witnesses. More than any priest, any doctor or any spy, the walls and ghosts of the Adelphi see humanity as we really are. What truths do they not know of us? No wonder their spectral voices taunt today’s pursuers.

‘No way,’ I told the receptionist firmly, when I got back to the front desk. ‘That room is haunted as hell!’

‘I know,’ she said, very matter of fact. ‘The only other one is by the lifts.’ This one was small and cosy and the lift fooled about all night, but I was perfectly happy.

There are only three certainties at the Adelphi. You never know what you will find. You will never forget your stay. And the ghosts, and all their stories, are included in the price.

Horatio Clare’s latest book, We Came By Sea: Stories Of A Greater Britain, is out now