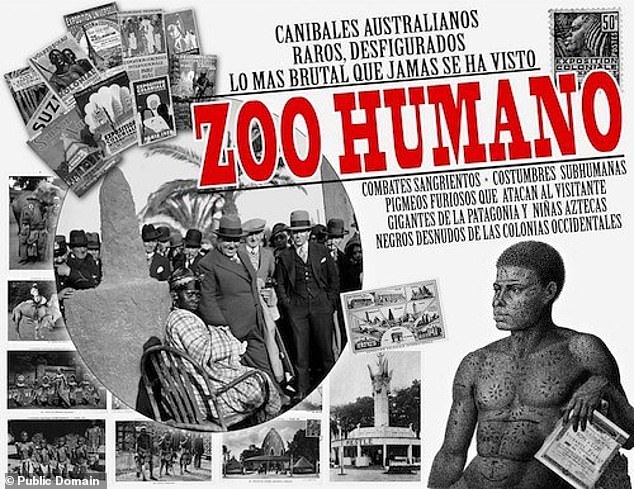

Caged in enclosures in Madrid’s Retiro Park, they were described as ‘strange’, ‘disfigured’, ‘brutal’ and ‘subhuman’.

It was in the spring of 1887 that Spain‘s Queen Maria Cristina inaugurated the Exhibition of the Philippines, and over the course of six months, thousands flocked down to the iconic location to observe natives from the Igorot tribe.

They had been shipped from the Philippines, then a Spanish colony, and were put on display as part of a practice that stripped them of their dignity and reduced them to curiosities for the entertainment of the public.

The troubling human exhibit was one of many across Europe at the time and was part of a widespread practice of displaying colonised populations in what came to be known as human zoos.

The first display in the Spanish capital featured 43 men, women, and children from the Filipino tribe and were described by newspapers with a mix of fascination and condescension.

Journal El Imparcial wrote that in their ‘constitution, appearance, language, manners, customs, color, and even clothing,’ they differed from the ‘most civilized and hitherto known Filipinos.’

European societies had developed an appetite for the ‘exotic,’ fuelled by colonial expansion and a growing market for human exhibits.

Organisers shipped colonised peoples from across the world to cities such as Paris, London, Madrid, and Berlin, where visitors paid to observe them in staged ‘villages’ meant to represent their daily lives.

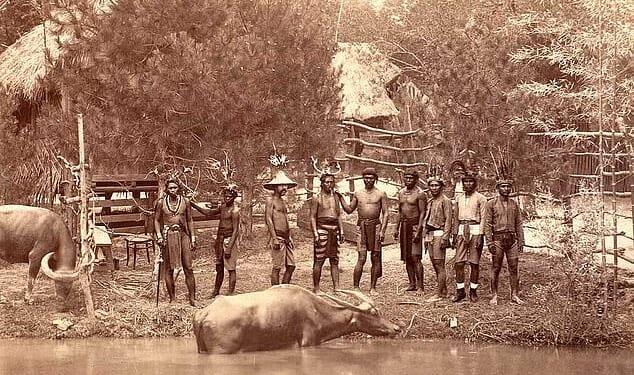

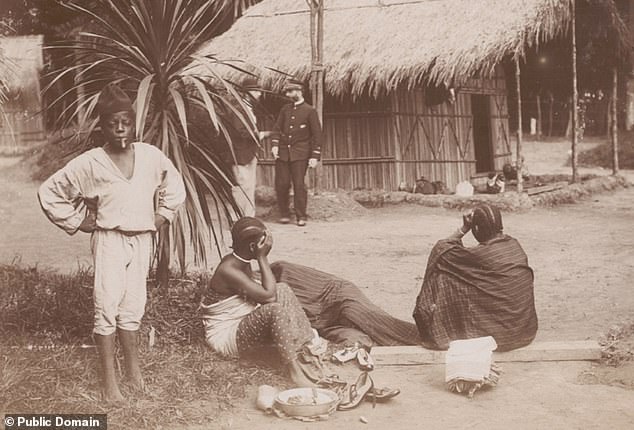

One of the few existing images of Madrid’s human zoo, which exhibited people from the Filipino Igorot tribe for six months in 1887 in the iconic Retiro Park

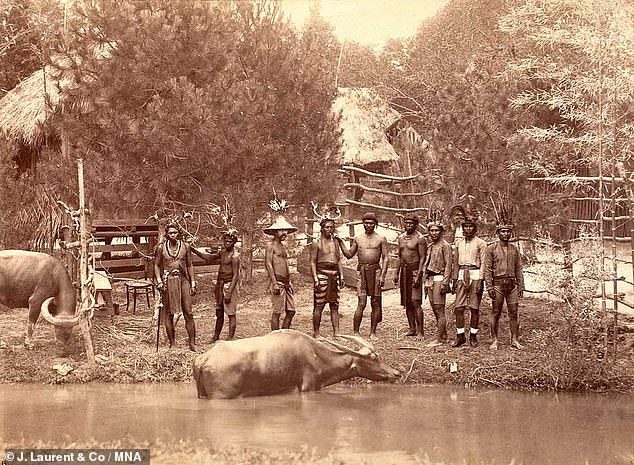

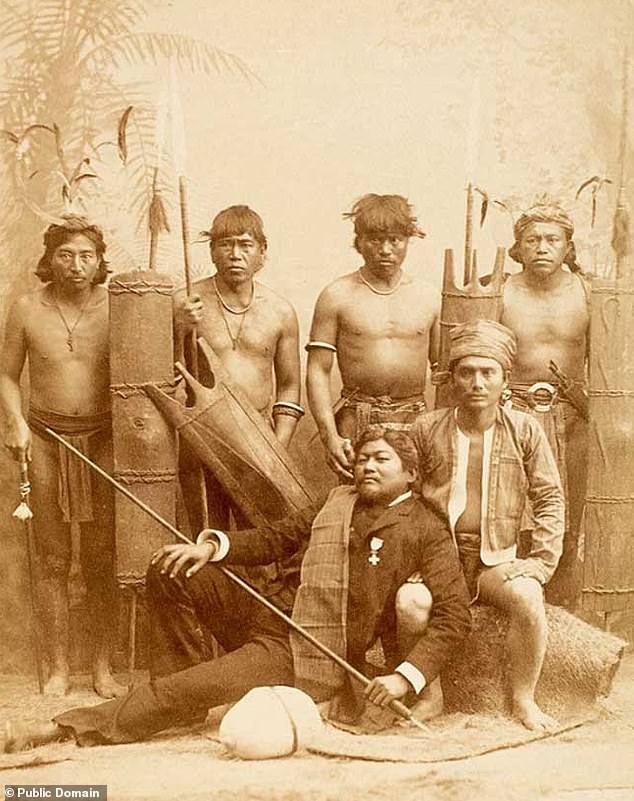

Filipino natives pose for a photograph in 1887 after they were brought over to Madrid to take part in a ‘human zoo’

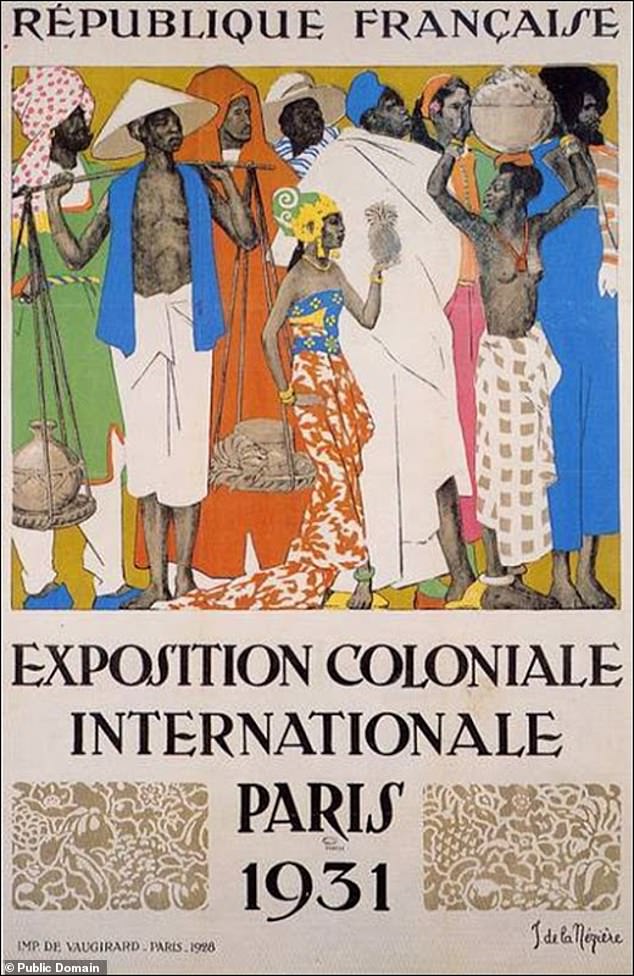

A poster depicting human displays, which became a common practice across Europe in the 19th and 20th centuries

Many were placed in fenced-off enclosures or makeshift settlements, forced to perform routines, rituals, dances, or simply go about their day while onlookers watched closely with morbid enchantment.

An entire village complete with thatched huts and places of worship was built in Madrid’s Retiro Park to exhibit the Igorot in an enclosure called ‘Casa de las Fieras’, or ‘House of Beasts’.

Organisers even built boats for the tribe and stocked the park’s pond with fish so that they could catch them for the public with their spears.

The tribe was eventually sent back home after Madrid rejected Paris’ request to borrow them for a display in the French capital.

Little else is known about the fate of the Filipinos who formed part of the human display in Madrid, but records suggest that at least four Igorots died as a result of poor living conditions during the exhibition.

A pamphlet produced by Spain’s Ministry of Culture for a 2017 exhibition revisiting the original 1887 Exhibition states that this ‘reaffirmed stereotypes surrounding these people, who were considered primitive or savage throughout the ‘civilised’ world’.

The document contains the few surviving photographs of the Igorot display, with the staged images showing naked tribes-people, depicting them as aggressive all while enforcing a racist narrative.

From the mid-19th century into the early 1930s, thousands of people – some voluntarily recruited, many not – took part in these exhibitions across Europe and the US.

Inside a mock Congolese village set up at the Brussels International Exposition in 1897

Tribes people had been shipped from the Philippines and displayed in an enclosure where they were stripped of their dignity and reduced to curiosities for the entertainment of the public. Pictured: A Filipino man in Madrid’s human exhibit

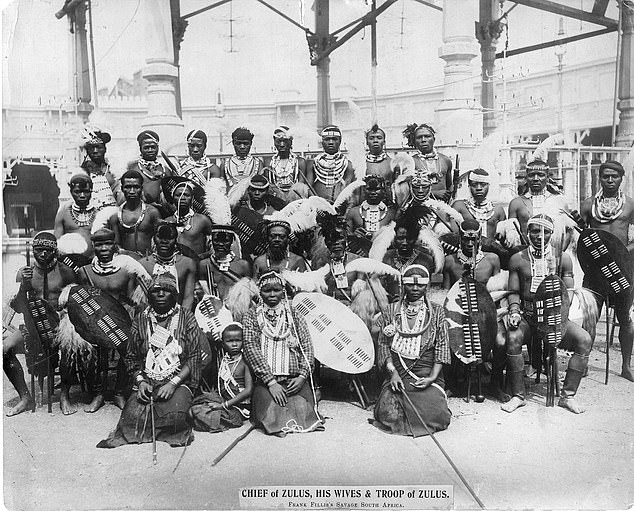

Africans are seen posing for a photo during the ‘Savage of South Africa’ exhibition in Earl’s Court, London

Horrifying images, some of which were taken as recently as 1958, show how black and Asian people were cruelly treated as exhibits that attracted millions of tourists.

Some of the people in the exhibits, in the late 19th and early to mid 20th century, were treated like animals and many died.

They included Ota Benga, a Congolese man exhibited in New York’s Bronx Zoo in 1906, who was shockingly described as a ‘missing link’ of evolution.

The dreadful exhibit sparked protest and outrage and Ota was eventually released. But six years later he tragically took his own life after being unable to assimilate into American life.

Estimates suggest that as many as 600,000 people were trafficked or contracted for such displays over several decades.

As public demand grew, the exhibitions became more elaborate, featuring reconstructed huts, enclosures, and entire mock villages inside major zoos and parks.

Some of Europe’s largest institutions hosted them, including the Tierpark in Hamburg, the Dresden Zoo in Berlin, the Jardin d’Acclimatation in Paris, and in Berlin’s Zoologischer Garten.

They became staples of world fairs and international exhibitions, where nations used them to showcase the populations of their colonies – and Britain was not exempt from the practice of human zoos.

Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II is pictured meeting Ethiopians standing behind a wooden fence in Hamburg, Germany in 1909

Filipinos are pictured in loin cloths sitting in a circle together at Coney Island in New York in the early 20th century while crowds of white Americans watch on from behind barriers

Ota Benga, a Congolese man, is shown, right, in New York’s Bronx Zoo in 1906

From the mid 19th-century until the early 20th century hundreds of Africans were brought over to Britain to be used as a form of touring entertainment.

Footage dating back to 1899 shows a huge group of Africans taking part in a mock battle that was performed multiple times a day in front of paying spectators in London’s Earl’s Court.

They were recruited from the Zulu and Swazi tribes by English circus impresario Frank Fillis to re-create the British defeat of the Matabele people in the 1890s.

The battle scenes were part of a show called Savage South Africa, and spectators could also wander around Kaffir Kraal, a mock-up of a Matabele village where they would see the same performers acting out their lives.

Also in London, an 1895 African Exhibition in Crystal Palace presented around 80 people from Somalia.

Elsewhere, citizens from French colonies such as Sudan, Morocco and the Democratic Republic of Congo were displayed in Paris’s Jardin d’Agronomie Tropicale between 1877 and 1912.

The first two human exhibits to be set up in the French capital presented Nubians – a Saharan ethnic groups, and Inuits from the Arctic regions.

Over the span of 35 years, around 30 human exhibitions were displayed in Paris, and they were so successful that they were even integrated in the city’s World Fair.

Racking up millions of visitors, the 1889 fair displayed 400 indigenous people and even exhibited a ‘Negro Village’.

This Inuit girl, pictured with a girl, was born at World’s Fair in Chicago. She was transferred to World’s Fair, St. Louis in 1904

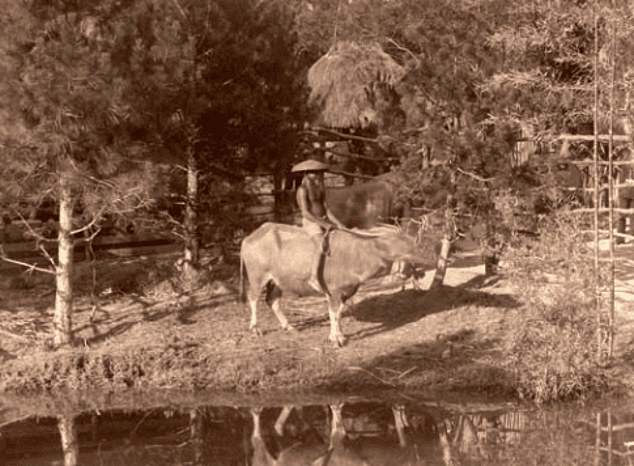

A Senegalese village set up inside of a human zoo at the World’s Fair in Brussels, Belgium in 1958

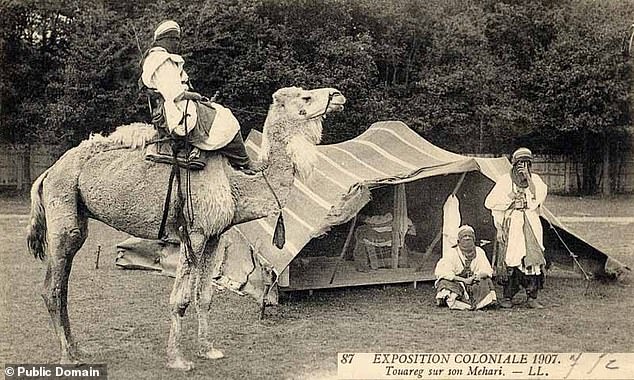

Tuareg camp at the 1907 Paris Exposition

A human zoo exhibition of the German animal merchant and zoo director Carl Hagenbeck, Germany 1930s

A poster for the 1931 human zoo in Paris

In 1907, residents of these mock settlements were returned to their homes and although more exhibitions were held, the space was left to ruin after the First World War.

It was reopened as a park in 2006 and visitors today can still see the abandoned pavilions and greenhouses once used by those who took part in Paris’ human zoos.

In 1883, Amsterdam displayed natives of Suriname at the International Colonial and Export Exhibition, and the 1897 Brussels International Exposition in Tervuren featured a ‘Congolese Village’ that displayed African people in what was meant to resemble a native setting.

Norway had a human zoo for five months in 1914, which included 80 people from Senegal living in a ‘Congo Village’.

More than half of the Norwegian population paid a visit to the exhibition in Oslo as the Africans wore traditional clothing an went about their daily routine of cooking, eating and making handicrafts.

The shameful industry also affected Australian aboriginals in the late 19th and early 20th century.

The shocking practice was detailed in a documentary called ‘Inside Human Zoos’.

Australian cinematographer Philip Rang, who worked on the film, said Aboriginal people were put on display as ‘boomerang throwing savages.’

The rise of the human zoo phenomenon is often linked to Carl Hagenbeck, the German animal trader who organised what is considered the first documented display of Indigenous people in Germany in 1882.

His model proved commercially successful and was soon adopted across the continent.

By the early 20th century, changing attitudes, criticism from some intellectuals, and increased awareness of the unethical conditions began to shift public opinion.

Yet the practice continued in various forms well into the 1930s, leaving behind a largely forgotten chapter of European cultural history.