Roger Ebert famously called cinema a great empathy machine, but movies are also nostalgia machines, especially when we feel like things are going wrong in the world. Look how well everyone dressed back then, we might say while watching North By Northwest; look how safe it was to walk the streets at night, we might observe with envy while watching Brief Encounter. This awakens in us a reactionary tendency which can be very illuminating, provided we reject that label as a cudgel and reclaim it as a tool to try and measure the distance between then and now.

The temptation to play games of compare and contrast is often heightened around Christmas. We compare our lives not only to the lives of others but also to the life we led the year before. Our cinematic favourites of the festive season are wistful portals and nostalgic blankets. Whether your Christmas movie of choice is Die Hard, Brazil, or It’s A Wonderful Life, there is something innocent about the ritual Christmas viewing, even if it involves John McClane running over broken glass, Sam Lowry being tormented by bureaucracy, or George Bailey contemplating suicide.

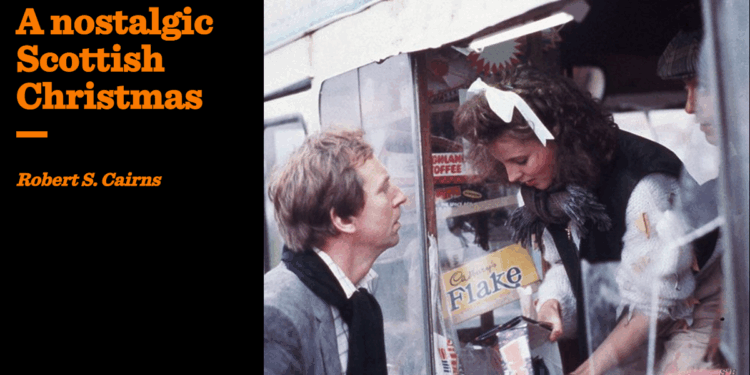

Bill Forsyth’s Comfort and Joy is another film deserving a seat at the Christmas table. It has the quiet dignity of an old Christmas jumper, albeit one with a distinctly odd pattern. As a Christmas odyssey of an everyman who, in mid-1980s Glasgow, gets caught in the middle of a preposterous turf war between two rival ice cream merchants, viewers will be surprised in equal measure by its farcical plot and its genuine lack of cynicism. It is a pleasure to laugh at our hero, Alan “Dicky” Bird, as he navigates his way out of his melancholy and becomes a version of himself he needs to be. The so-called normal life of today seems deeply unfunny by comparison.

It could be argued, in the vein of the famous “It’s Shite Being Scottish” monologue in Trainspotting, that the Scotland of the 1980s was not a place to get overly nostalgic about. In particular, Glasgow’s reputation as a rough, ship-building city is obviously not unwarranted. The real-world “Glasgow Ice Cream Wars” involved gangs using ice cream vans as cover for organised criminal activity. Bill Forsyth was not naive to these rough edges of his city. His debut, That Sinking Feeling, is charming but has a more kitchen-sink approach to Glasgow, so much so that American critic Vincent Canby described it as a film “in which just about everyone has a skin problem”.

With this in mind, the gentle, fable-like quality of Comfort and Joy deliberately eschews some of the harder realities of its time and setting, making it somewhat reactionary even back in 1984. Glasgow, warts and all, has been put under the magnifying glass by other filmmakers (the recovering-alcoholic drama of Ken Loach’s My Name is Joe, the doldrums escape fantasy of Lynne Ramsay’s Ratcatcher). Every time I watch Comfort and Joy, I realise it deserves a place in the pantheon of cracked-up, mock-Homeric Odysseys, alongside the likes of After Hours or The Big Lebowski. It must be very tempting for a director to make an artistically ponderous slice of miserabilist social realism, and it says a lot that Comfort and Joy is a feel-good film instead.

In the years since Comfort and Joy’s 1984 release, we have seen changes in Scotland, the UK, and Europe that make the film seem much older than it actually is. In 2013, the decapitation in broad London daylight of British soldier Lee Rigby was a formative event for me. I recall how my father, born and raised in Fife and never shy to throw a playful barb at the English, pivoted to a more general sense of British solidarity. “That should be the end of that”, he remarked in reference to the obvious literal and symbolic incursion. Sadly, that was not the end of that.

Instead, Scotland received its own dose of the unfortunate byproducts of forced diversity in Europe: Sharia councils, grooming gangs, a Glasgow where almost a third of the children don’t speak English as their first language, and a former First Minister who has volleyed openly hostile rhetoric towards native Scots. Curiously, the First Minister in question, Mr. Humza Yousaf, was born into the Glaswegian world of Comfort and Joy in 1985, one year after the film’s release. Who could have foreseen what was coming down the pike?

In the wrong kind of mood, a film like Comfort and Joy can feel confusing and depressing when weighed up against these shifting realities. At a time when the holiday season in Europe routinely requires barriers to stop vehicular terror attacks at Christmas markets, Bill Forsyth’s story of opportunity and ice cream can feel rather quaint. There’s an irony, too, when we consider the fact that the film believes in the possibility of some sort of meaningful reconciliation with foreigners. An important part of our protagonist’s character arc, after all, is asserting himself with an entrepreneurial tact and ingenuity amongst the Italian and Chinese communities of his neighborhood.

The presence in Forsyth’s story of small Italian and Chinese groups is proportionally incomparable to the growing feeling of the present day, recently admitted even by Labour PM Keir Starmer, of the UK being “an island of strangers”. Comfort and Joy still had a romanticism about being part of a bigger world because the wider world was further away. The radio playing in the background of many scenes gives us updates about the Panda Diplomacy of the 1980s and the political strife in Burundi. This situates the Ice Cream Turf War, absurdly, in a global context. Although played for laughs, the gesture of Panda Diplomacy and the tensions in Burundi come to represent a more profound choice our character needs to make about his own inner torpor. He needs only to solve his own problems, not the entire world’s.

There is a lesson here for the viewer to both temper and take seriously their reactionary spirit. Forsyth’s Comfort and Joy, as the poster tagline says, is “a serious comedy”. We should take it seriously and allow it to uplift us, lest we get too lost in comparing and contrasting. In keeping with our Scottish theme, let’s reflect on the past and the future by remembering the words of Robert Burns’ “To a Mouse”, which the children of Scotland, whatever language they may speak, are hopefully still learning at school:

Still, thou art blest, compar’d wi’ me!

The present only toucheth thee:

But Och! I backward cast my e’e,

On prospects drear!

An’ forward tho’ I canna see,

I guess ‘an fear!