The five black-and-white images are grotesque. A young Asian woman is pictured in a variety of sexual poses, sometimes naked, sometimes in cheap lace lingerie. In one, she is performing oral sex on a man whose face you cannot see. It’s pixellated but there is no mistaking what’s happening.

‘Welcome to visit me!’ says a caption in fractured English. Another box boasts her bust, waist and hip measurements. It’s clearly advertising her services as a prostitute.

Today, the 30-year-old woman in the photos is sitting directly opposite me, looking very different. She’s warmly wrapped against the December chill, fluffy Ugg boots on her feet and a sad, defensive look on her face.

She is Carmen Lau, a pro-democracy activist who fled Hong Kong seeking sanctuary in the UK four years ago. She had expected to find refuge here. Instead, the state-sanctioned Chinese persecution that forced her from her home has crossed continents and arrived in Berkshire.

The pictures are fakes generated by artificial intelligence. They were created to besmirch her reputation and compromise her personal safety, and were mailed directly to Carmen’s neighbours from the semi-autonomous Chinese territory of Macau.

‘No one should be targeted with such sexual violence,’ she says. ‘I feel angry, I feel betrayed, I feel terrified. People who know me, they understand it isn’t me in those pictures, but what about all the people who don’t? And who knows how widespread these images are now, how far they have been shared online.’

Carmen was in Berlin at a political event when her MP Joshua Reynolds telephoned to say half a dozen constituents had reported receiving pornographic images of her.

‘He said, ‘Before I send them over, I do need to warn you…’ so I was prepared. But when I opened the file, I was still shocked because they looked so real. The thing that angers me most is that I have no idea how to hold these people accountable for what they’ve done, how to find justice.’

Carmen Lau (pictured) is a pro-democracy activist who fled Hong Kong seeking sanctuary in the UK four years ago

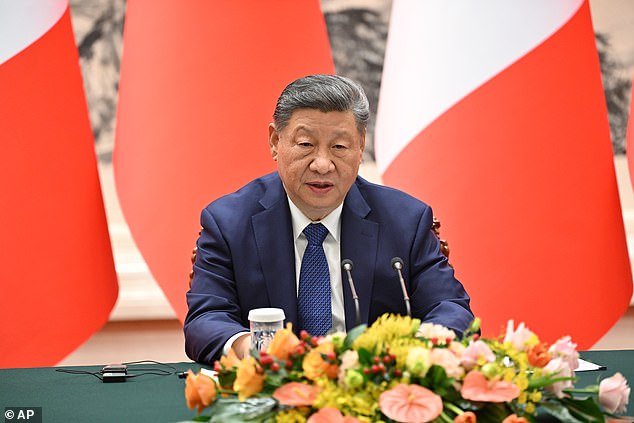

UK Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer during a bilateral meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping. The British PM is rumoured to be heading to China for a diplomatic visit next month

Sadly, last month’s attack is just the latest salvo in a Chinese campaign of transnational harassment against Carmen and other UK-based dissidents, which the British police and No 10 have been unable to stop.

Earlier this year ‘Wanted’ posters offering Britons a reward of one million Hong Kong dollars (about £95,000) for information about Carmen – or for dragging her to the Chinese Embassy in London – were also mailed directly to her neighbours. She also suspects she has been followed and watched while working in the UK.

And her ‘crime’? Carmen stands accused of ‘incitement to secession, and collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security’, from her time working as an elected councillor in Hong Kong – charges she doesn’t even deign to deny, since they are ‘manufactured and unjust’.

The campaign of harassment against her raises two serious questions for Britain. First, how can Sir Keir Starmer befriend Beijing when, as expected, he visits China next month? And second, why is the government set to allow China to build a mega-embassy in London, with its associated threat of increased spying and sabotage on British soil?

In person, Carmen Lau couldn’t look less like an enemy of the state. She’s small and slight in faded denim, dark hair framing her face. She speaks quietly and earnestly, without hyperbole or a scrap of self-pity, despite being effectively trapped in a country that might be familiar, but isn’t home.

Heartbreakingly, she has no clue when – or if – she will be able to return to Hong Kong where she worked as an aide to a pro-democracy politician and then successfully ran for local election herself.

Since Hong Kong has only one layer of administration below its legislature, becoming a councillor put her in a position of genuine power. This victory enraged Beijing, which has been clamping down on democracy in the former British colony since 2019.

Soon Carmen found that her office in Kowloon was being watched, and colleagues and visitors photographed. In early 2021 a Beijing-run newspaper published a front-page story accusing her of conspiring against the Chinese government. Rumours began to circulate that councillors like her were on a hit list for arrests, while £20,000 of public funding, the cost of running her office, was withheld.

Carmen stands accused of ‘incitement to secession, and collusion with a foreign country or with external elements to endanger national security’

When a white Toyota SUV – the kind favoured by China’s security services – trailed her home in Hong Kong with an agent filming from behind its blacked-out windows, Carmen understood her family was being targeted, too.

‘By then we were all living in fear,’ she says. ‘They were taking people from their beds at 5am, at their most vulnerable.

‘The sight of that Toyota made me paranoid that I could be snatched off the street. I knew my work had consequences, that I might be arrested, but this was the first time they’d made me scared for my parents.’

Fearing for her safety, and also believing she could do more to help Hong Kong as a free exile, in July that year Carmen fled, buying a return ticket to London to avoid arousing suspicion at the border.

‘I didn’t say goodbye to anyone,’ she recalls. By September, she publicly announced she had settled in the UK, triggering a barrage of online harassment from Beijing’s bots and trolls.

‘There were death threats, rape threats, I was called the C-word, told I was serving white men, or the CIA.’ She shows some screen shots: ‘A bitch like you will be raped and killed by anti-China [sic] in the west once you are no longer useful,’ reads one.

As a result, Carmen takes stringent security measures with CCTV outside her temporary accommodation and motion sensors inside it. She has upgraded her electronic security following official warnings from Google about repeated state-sanctioned hacking attacks.

She uses fake names for online services such as Amazon and Uber, has burner phones and a permanent VPN – software that hides a user’s origins and bypasses geographic restrictions on websites.

Carmen takes stringent security measures with CCTV outside her temporary accommodation and motion sensors inside it

Travelling abroad, she takes pains not to fly through Chinese air space or touch down in a country that has an extradition agreement with Beijing.

But China has been undeterred, repeatedly harassing her in blatant defiance of diplomatic convention, British sovereignty and the rule of UK law.

The attacks escalated in December last year when Hong Kong police issued a warrant for Carmen’s arrest, along with the one million Hong Kong dollar bounty. It was March when the ‘Wanted’ posters were mailed to the UK and then last month came that devastating fake porn attack.

It’s little wonder then that she is angry at the prospect of the British government thawing relations with President Xi Jinping and Beijing, and deeply alarmed at No 10’s naivety in relation to China’s new mega embassy, which looks set to receive planning permission next year. ‘This prioritising of economic interests [over human rights], this cosying up to China, it signals to whoever’s out there that they can act freely in the UK,’ she said.

‘Such friendship between Keir Starmer’s government and Beijing will allow new ways for repression to grow on British soil.

‘It’s an illusion, seeing China as an economic partner. Starmer’s government might think they’re really good at navigating a relationship with China, naming it as a threat to the UK, while at the same time shaking hands with it for trade deals, but that’s not how it works because, with China, you will never get the win. Starmer is deluded.’

As for the new embassy planned in the old Royal Mint Court next to the Tower of London, she’s equally appalled. ‘Every step of the decision is wrong: it’s diplomatically wrong, historically wrong and wrong for security. The UK is a democracy while China is not. Why would you allow an autocracy to have this outpost, especially on an historic site?

‘It’s a fortress, the footprint of a rival state in the British capital –not to mention the fact the Chinese have blurred out their plans for some of the rooms. You can see from the history of terror regimes that they are very good at torture and interrogation.’

Carmen doesn’t need to spell out that, for someone considered a hostile actor by China, a suite of secret basement rooms in the country’s London embassy is a terrifying prospect. And sadly she has limited faith in the British police’s ability to protect her.

Until the distribution of the pornographic pictures, Thames Valley Police’s response had been to ask her to stop provoking China by speaking out.

It’s little wonder then that Carmen is angry at the prospect of the British government thawing relations with President Xi Jinping (pictured)

‘They gave me a Memorandum of Understanding,’ says Carmen. ‘They said signing it acknowledged that continuing [to campaign] was my own choice.

‘I asked for physical protection but they said my risk wasn’t high enough to warrant extra resources.’ But the most recent harassment has made police sit up – although their door-to-door inquiries and a forensic examination of the letters have yet to yield a lead.

‘Things have improved now,’ she acknowledges, ‘because gender-based harassment is something they prioritise.

‘And,’ she sighs, ‘I have set the bar of my expectations lower.’

Carmen grew up in a cosmopolitan Hong Kong family. Her globe-trotting father ran a jewellery business while her mother was the daughter of a fishing family on Lantau, the largest of Hong Kong’s islands where her relatives still live in a traditional house on stilts over the water.

She misses her home, and her family and friends, sometimes walking around the City of London looking at its skyscrapers and thinking of the iconic Asian skyline she loves.

‘What keeps pushing me forward is the people of Hong Kong. It’s not about the place itself and it’s certainly not about power,’ she says. ‘It’s about our people. Sometimes I think I will never be able to go back and I feel very small as a person out in the world. But anything that happens to me here is nothing compared to those who have already sacrificed their freedom.’

What a tragedy that Britain, with its historic responsibility for Hong Kongers and its ancient tradition of liberal democracy, cannot do more to protect Carmen so that she, in turn, can protect those left behind.