This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Time was when film music composers weren’t taken very seriously. More than that: any classical composer whose music was deemed to have pre-empted film music was regarded with scholarly suspicion. Rachmaninov suffered posthumously from this “taint”; so did Puccini.

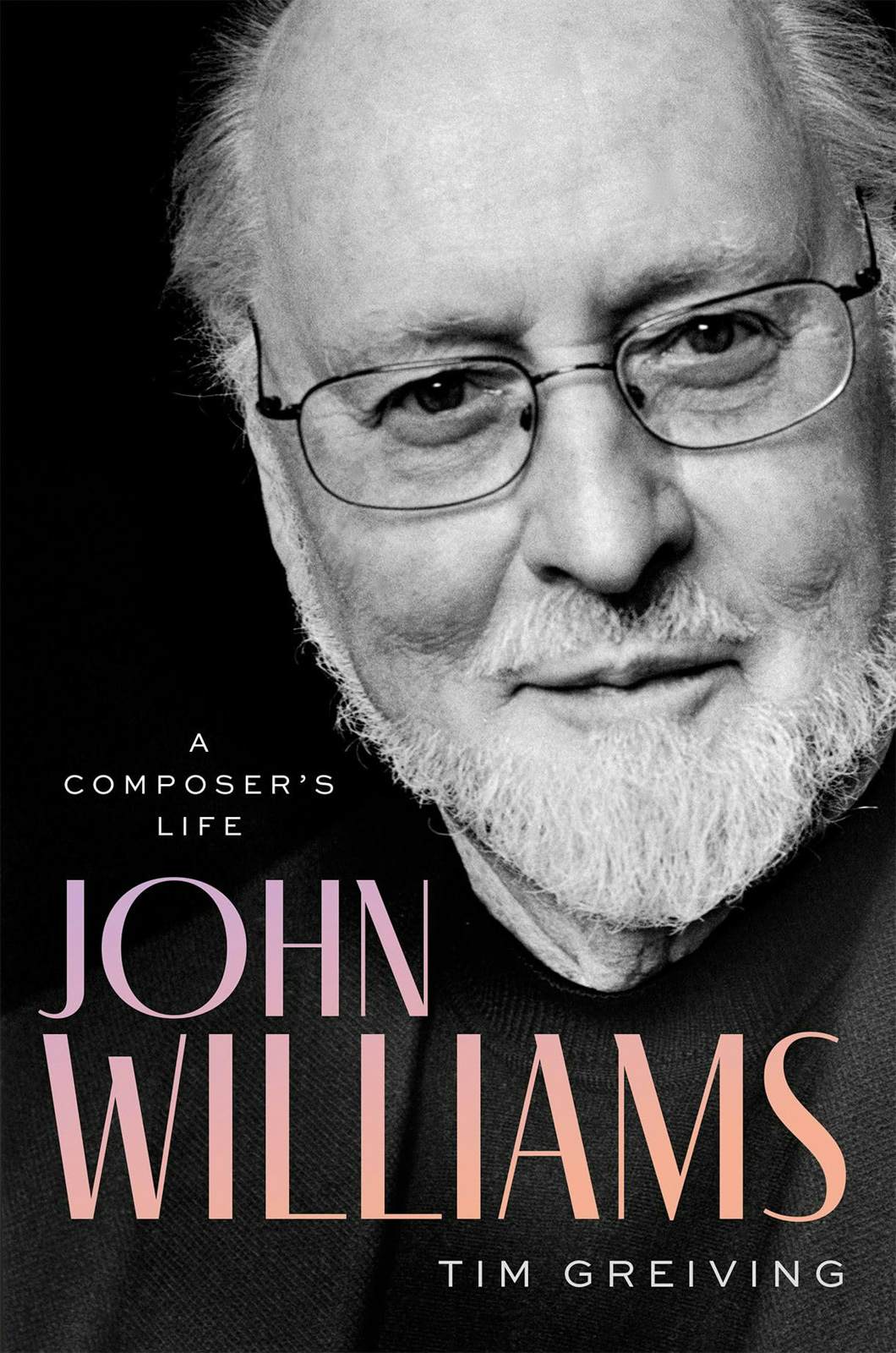

How things change. Today musicology foregrounds popular repertories, and in some institutions students are more likely to study film music than the works of the now “suspect” classical canon. It is a sign of the times that John Williams, Hollywood’s most well-known tunesmith, should have Proms concerts dedicated to him, and now be the subject of a doorstopper of a biography from a major academic press.

Born in Queens, New York, in 1932, the son of a session drummer, Williams was exposed early to the world of showbusiness. It was sitting in on rehearsals at the CBS Radio Theatre that introduced him to what would become his greatest passion: the orchestra. Piano lessons followed, and Williams became a keen orchestral arranger.

Film, at this stage, was not a particular interest, but was always hovering in the background as the family shuttled back and forth between New York and Los Angeles, where Williams Sr ultimately joined the staff orchestra of a Hollywood studio.

But Williams himself was no nepo-baby: his success was the result of innate dedication and hard graft. A highly self-driven individual (though never a self-promoter), he practised the piano four hours a day, gained an encyclopaedic knowledge of the classical canon, and approached music as an intellectual. His daughter later said that although she didn’t hear much classical music at home, she often saw her father reading scores as if they were books.

Williams’s ethos was one of steely discipline: “It’s like someone who’s going to study medicine. There’s only one way to do it, and that is: do the work.” Intriguingly, he believes he would have become a modernist composer had he not been drafted into an air force band and been given responsibility for arrangement, which sent his career off in an entirely different direction. John Williams the serialist manqué — who’d have thought it?

Greiving, an arts journalist and film music scholar, talks the reader through the technicalities of leitmotifs. He analyses the precise sources of Williams’s “conspicuous nods to the classical repertoire” (Jabba the Hutt’s “Prokofiev-like theme” and so on), whilst always maintaining an appealingly readable tone. (“Almost all of John’s movies before this were like flat cola. Spielberg’s films, by contrast, fizzed.”)

He documents Williams’s development as a composer in meticulous detail, discussing the business of film music at both macro and micro levels: how it functions institutionally and what the composer actually does to create what Williams calls “underdialogue”.

Williams’s career began at a time, in the late 1950s, when 650 musicians were employed in in-house studio orchestras. He was therefore a witness to the final days of classic “golden-age Hollywood” as well as to everything that has followed since, keeping “symphonic” scores alive long after they might otherwise have fallen from fashion. Even if you don’t care personally for the soundtracks to Star Wars or Indiana Jones, this is fascinating stuff.

We catch only glimpses of personal hinterland, but Williams emerges as a gentle, stoical man, who has faced unimaginable personal sorrows yet kept up astonishing levels of productivity. He only scaled back slightly on ten-hour days when he reached his eighties, and writes instrumental concerti as a “holiday” from film work.

If the blockbuster soundtracks written for his long-time collaborator Spielberg have been criticised for “all sounding the same”, the younger Williams was chameleon-like, effortlessly turning his hand to any musical style required of him.

He has responded most intuitively to intensely human subjects: Schindler’s List came easily; Jurassic Park meant “chiselling out” every note. He has unashamedly prioritised emotion, romance and nostalgia — qualities that have simultaneously been the secret of his success and the prompt for much sneering from his peers.

An intensely private individual, Williams did not want to be the subject of a biography. However, having established that Greiving was not “some drooling fanboy”, he eventually agreed to talk over a period of 18 months. This is a tacitly authorised biography, then, and one so exhaustive that it is hard to see there ever being a need for another.

Williams is aware of being a craftsman, paid to provide whatever his paymasters have demanded, and from time to time that has meant providing musical popcorn. Make no mistake, though: this is a serious book about a serious musician.