This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

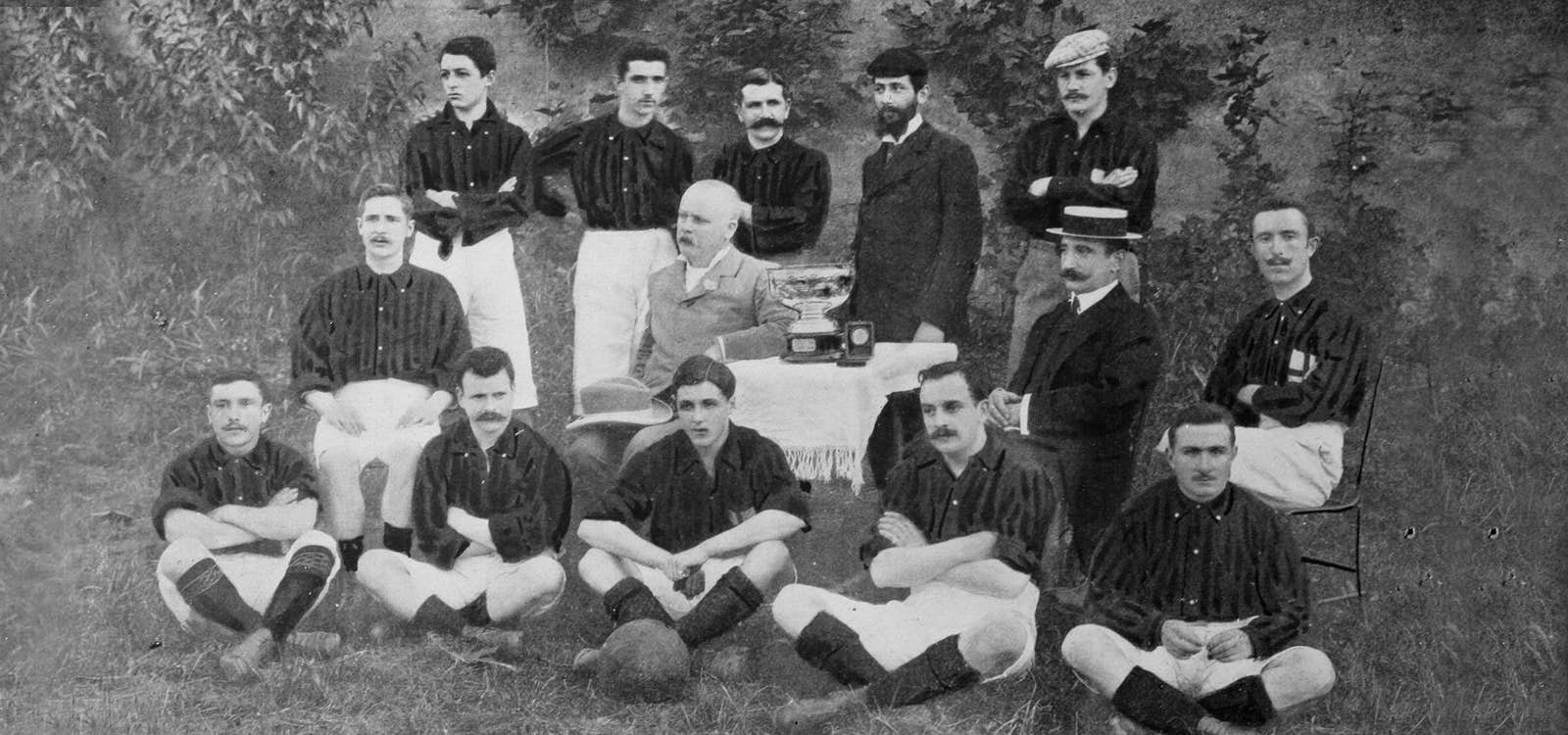

St Syrus knew how to make a little go a long way. According to legend, the 1st century bishop was the youth in St John’s Gospel who produced five barley loaves and a couple of fish from which Christ rustled up supper for 5,000. Two millennia later, a similar transformation happened in a district of northern Italy that bears the saint’s name, when a cricket club founded by an expatriate lacemaker from Nottingham evolved into one of the wealthiest football sides in the world.

The cricketers who Herbert Kilpin recruited in Milan quickly realised that they preferred AC to CC. Playing football in the red and black striped jerseys of Notts Olympic, whom Kilpin represented before he moved to Italy in 1891, they won the Italian league title in 1901 using as their home ground a patch of recreational land that had no stands or dressing rooms, then moved to four other grounds before settling a century ago in the San Siro suburb to the northwest of the city.

The turf was broken for a new stadium, funded by the tyre giant Piero Pirelli, in December 1925 and AC Milan hosted their first match there nine months later against their big city rivals, Internazionale, who had been formed in 1908 after a schism at Kilpin’s old club over whether they should court more foreign players. Inter won 6-3. For the past 78 years, Milan’s two biggest clubs have been joint tenants of the ground, which was owned by the city council.

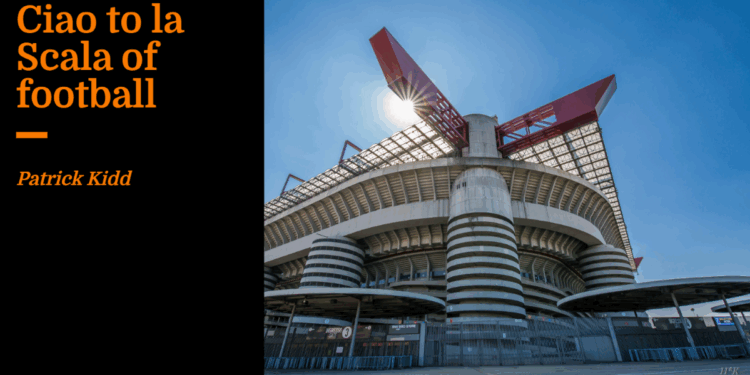

The San Siro is one of those stadiums, like Wembley, Anfield and Twickenham, that is known around the world by its location, even though since 1980 it has technically been called the Stadio Giuseppe Meazza, after a former player for both clubs. Over a century, it developed into Italy’s largest and most famous football stadium, staging matches at the 1934 and 1990 World Cups and four European Cup Finals. In February, it will host the opening and closing ceremonies for the Winter Olympics.

With its spiralling access towers, which look like giant springs and give the optical illusion that they are rotating when the crowds walk down, and the orange girders that jut out of the roof, the San Siro is distinctive. FourFourTwo magazine put it at No 10 in a list of the world’s 100 greatest grounds, one place behind Wembley and two ahead of Real Madrid’s Bernabeu. Some call it La Scala del Calcio — football’s opera house — but soon the curtain will be coming down.

Milan and Inter have wanted to build a new stadium for several years. The San Siro is now in poor condition, with sections of the upper circle closed because of a worrying wobble when fans jump up and down, cutting its capacity by 5,000, and it is no longer considered good enough to be given international matches or major club finals.

FourFourTwo compared the stadium to one of the city’s other works of art that was also once in desperate need of saving: Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper in the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The San Siro, however, cannot easily be restored. In September, the council agreed to sell the stadium to the clubs, who intend to build a new oval one right next door that would open in 2031. The decision to give the 2032 European Championship to Italy, which will co-host it with Turkey, has focused minds.

The new stadium will doubtless be magnificent, but what is perhaps more heart-warming is that after more than 70 years of living with each other, two clubs with such a strong rivalry still want to continue to share a ground. It is not unknown in Italian football — Lazio and Roma have shared the Stadio Olimpico since 1953 and Juventus were lodgers at the home of Torino that is no longer called Stadio Benito Mussolini for more than 50 years — but rare at the top end for clubs in this country.

It may be an oddity that the highest attendance at Manchester City’s old Maine Road ground was for Manchester United against Arsenal in 1948, but that was during a temporary stay whilst the damage sustained by Old Trafford during the war was being repaired. Tottenham Hotspur’s White Hart Lane similarly gave Arsenal sanctuary when their own Highbury was requisitioned for use as an Air Raid Precautions centre in 1940, but these were wartime emergencies. You couldn’t see it happening now. Big English clubs have too much ego to share.

In Milan, however, the huge clubs are happy bedfellows despite their sporting rivalry and cultural difference. Inter were traditionally the club of the bourgeoisie, who went to the games by moped, Milan of the bus-riding working class, but the groundshare worked. The San Siro has three dressing rooms — one reserved for each Milanese club and a third for visitors — to avoid the problem of deciding who is at home when they hold the Derby della Madonnina, after the statue on top of Milan Cathedral.

After 244 matches between them, Inter lead 91-82 and the Nerazzuri, who play in black and blue stripes, have had slightly more domestic success than the Rossoneri, winning 20 league titles to Milan’s 19 and leading 9-5 in Coppa Italia victories. But the San Siro’s original owners lead 9-6 in European trophies. It seems that the Madonnina does not have a favourite team. Though I suspect Milan might still have the edge in cricket.