This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Christmas, and the family gathers round the television for a little light murder. On Netflix, after a throat-clearing cinema release to establish that this is definitely a real film, we get a new Knives Out mystery.

Rian Johnson’s first film in this series was a blast of fresh air in 2019. It felt like something completely new, even though it was recognisably doing something pretty old: a country house murder mystery for the 21st century.

The formula was a complicated twist-laden crime, a cast of A-listers enjoying themselves in loathable character roles, and Daniel Craig struggling with a New Orleans accent as master detective Benoit Blanc.

The films are both funnier and nastier than Agatha Christie, and there is a constant danger of falling into pastiche. Blanc’s second outing, Glass Onion, suffered from that, and the result was silly and hammy and unmemorable.

The third Blanc film, Wake Up Dead Man, avoids the trap, largely thanks to star Josh O’Connor. He plays a young Roman Catholic priest sent to a New England parish where a monster monsignor, played by Josh Brolin, is building a cult around himself. When his boss is killed in an apparently impossible murder, O’Connor finds himself in the frame. But — brace yourself — this is a congregation with plenty of secrets.

Just as Ana de Armas was the first film’s heart, O’Connor is this one’s. Whilst master detective Benoit Blanc is a man of rationality who sees the church as a house of fairy stories, O’Connor is a great counterbalance as a priest with a violent past who now wants to offer the love of God to his flock.

The small moment, two-thirds of the way through, where he suddenly remembers his calling mid-phone call is a terrific piece of character drama that could have sat in a much more serious film.

O’Connor and Cailee Spaeny, playing a wheelchair-bound cellist desperate for healing, together ground a plot that otherwise verges on the ridiculous, and allow the rest of the cast, including Glenn Close and Andrew Scott, to play for laughs.

If you prefer a previous vintage of sleuth, then seek out Silent Sherlock, a restoration of three films made between 1921 and 1923, starring Eille Norwood as the greatest detective of them all. These have been beautifully restored and given new musical scores.

I approached them initially as historical curiosities: an early movie series from a time when people were still working out how to tell stories in the medium.

But by the time we got to the third film, The Final Problem, I found myself gripped as the camera cut back and forth between Sherlock Holmes and Professor Moriarty wrestling and a faithful Doctor Watson dashing to the rescue, just too late.

I didn’t even mind that the action had been moved from the exotic Reichenbach Falls to the slightly bathetic Cheddar Gorge. Norwood was apparently Arthur Conan Doyle’s favourite Sherlock Holmes actor, though of course he never saw Jeremy Brett.

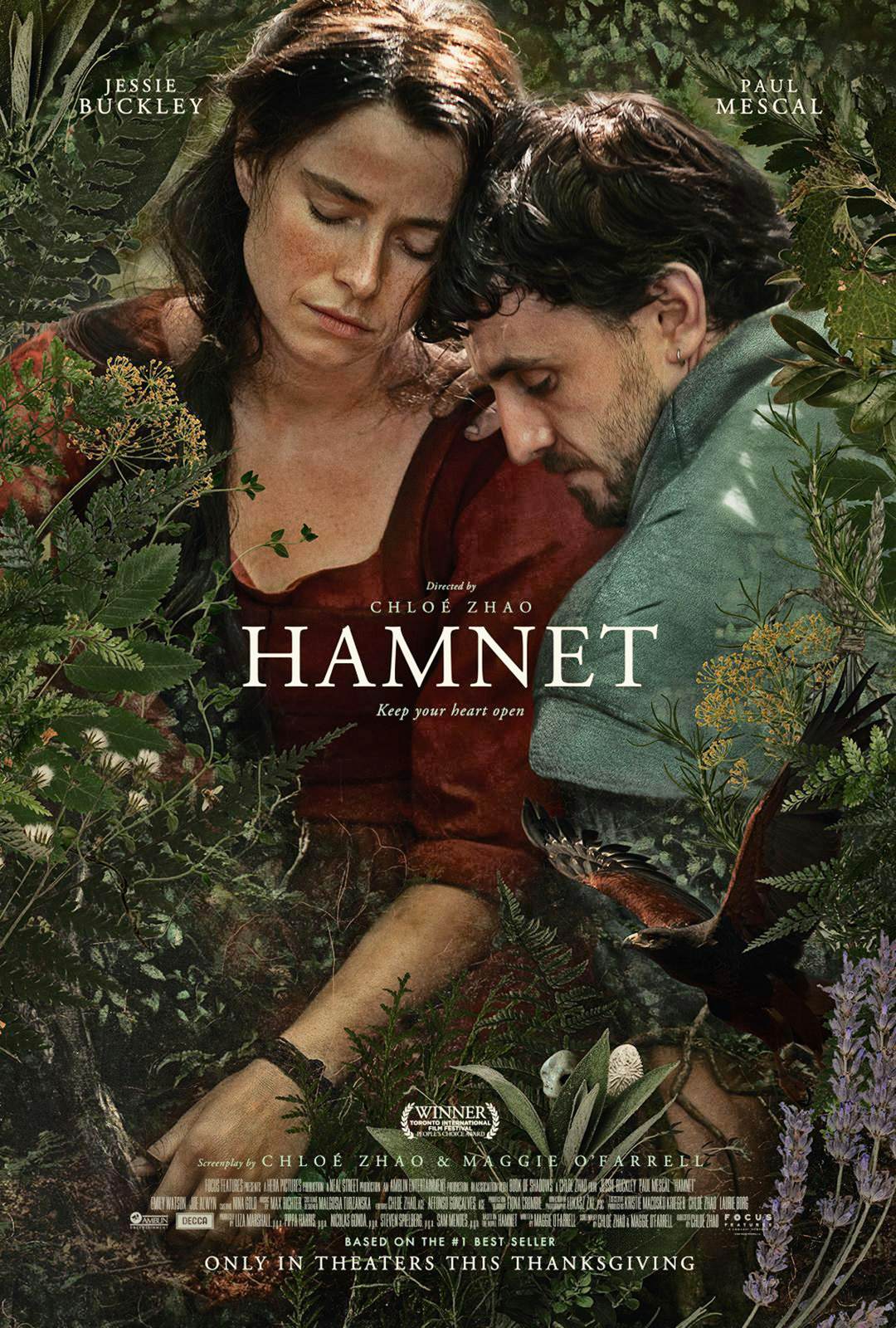

Into January, and Hamnet sets the bar very high indeed for the rest of 2026. I hadn’t read Maggie O’Farrell’s book, or seen the stage play of it, so all I knew about this film was that it was a story about William Shakespeare and his son, whose name was, we learn from the titles, considered identical to Hamlet in the 16th century.

I suppose I’d expect the story to focus on the playwright, but in fact Paul Mescal’s Will is a supporting actor to Jessie Buckley’s Agnes, whose story this is. Strong-willed, and suspected by Will’s mother of being a witch, Agnes would be a worthy addition to the journalist Helen Lewis’s collection of Great Wives. She encourages her husband to seek his fortune in London whilst keeping the home fires burning back in Stratford.

She refuses to join him in the big city because of her fears for the health of their daughter Judith. But when Judith falls ill, it is her twin brother Hamnet who dies, plunging father and mother into a grief that makes them strangers.

This is a film of women, made by women (O’Farrell shares a screenwriting credit with director Chloé Zhao) about the lives lived by women whilst men are off making history.

We see Agnes labouring, both in the birth sense and on the home front, and caring for her children, and mourning her son. Through it all, Buckley is quite brilliant. Where has she been until now? What will she do next?

I often think how unusual it is, in human history, to expect all your children to live to adulthood. Both my grandmothers lost children in infancy with husbands far away, though they could at least blame a global war for that bit.

Today we would see such loss as a major trauma. Did previous generations just accept it? Hamnet gives us both options, with Emily Watson, as Will’s mother, quietly bearing losses she never discusses, and Agnes unable to think of anything else.

Films about grief can easily be manipulative. Like the couple of thousand other people watching the film with me at the London Film Festival, I was crying for most of the second half. But Hamnet stays on the right side of the line.

You don’t need to believe that the tragedy is what inspired Shakespeare to write his greatest play to be moved by a story of pain and the healing power of art.