Our soldiers lack the ammunition, combat supplies and medical support to fight a war

This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Writing in the Spectator last month, the military historian Allan Mallinson wondered “how many people appreciate what a remarkably capable army we had — and how incapable that Army has become?”

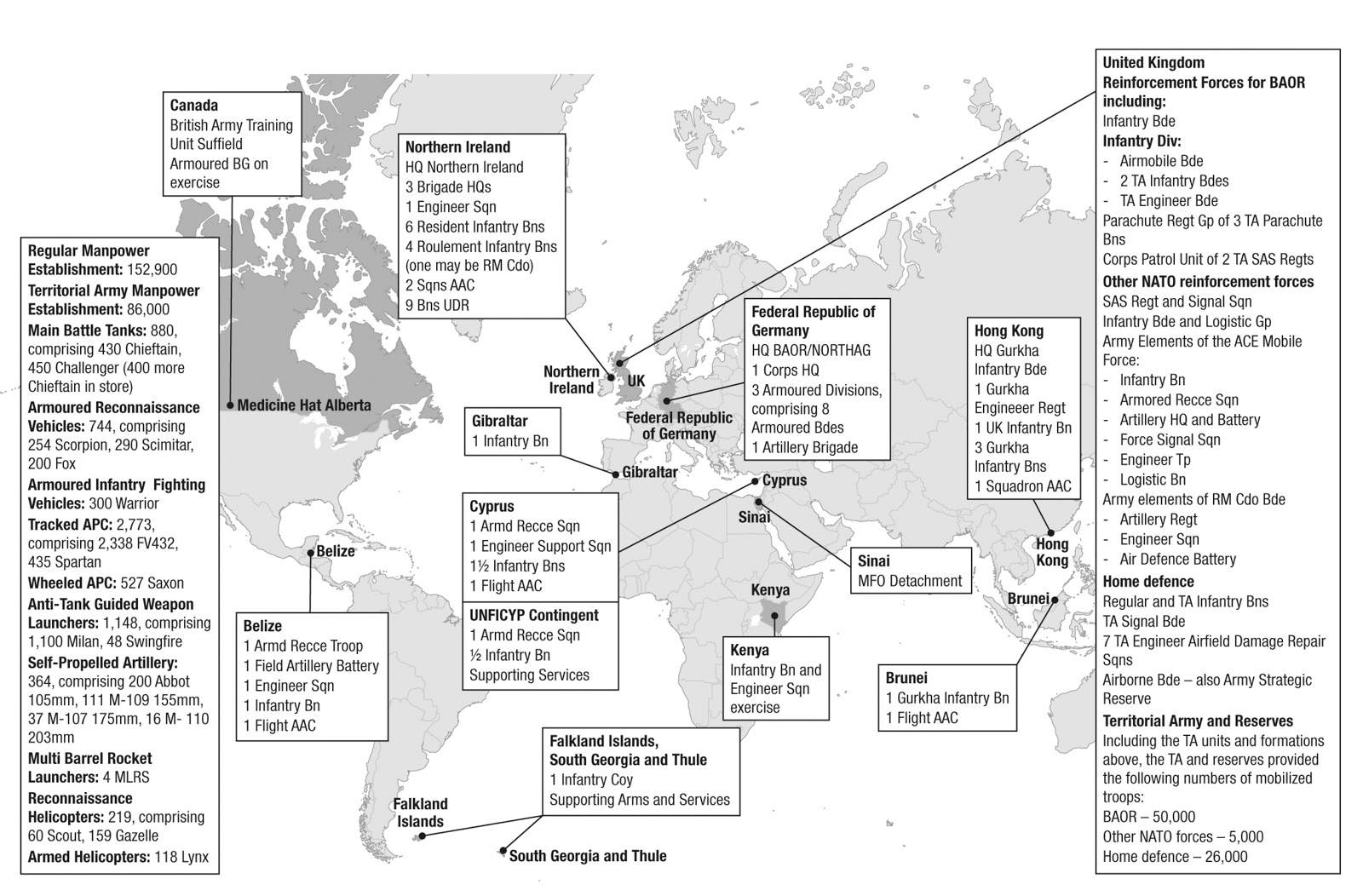

In my book The Rise and Fall of the British Army, 1975-2025, I explain how the Army’s fighting power increased during the 1980s. General Sir Nigel Bagnall encouraged tactical innovation and a revolution in doctrine for armoured manoeuvre warfare. The Thatcher government’s rising defence budget funded new weapons, including Challenger tanks and Warrior infantry fighting vehicles, sustained military salaries and increased the size of the reserves in the Territorial Army.

It also sent many troops to Northern Ireland whilst relishing the unanticipated challenge of the Falklands War. The Parachute Regiment and the SAS were at the cutting edge, their thirst undimmed for action and adventure.

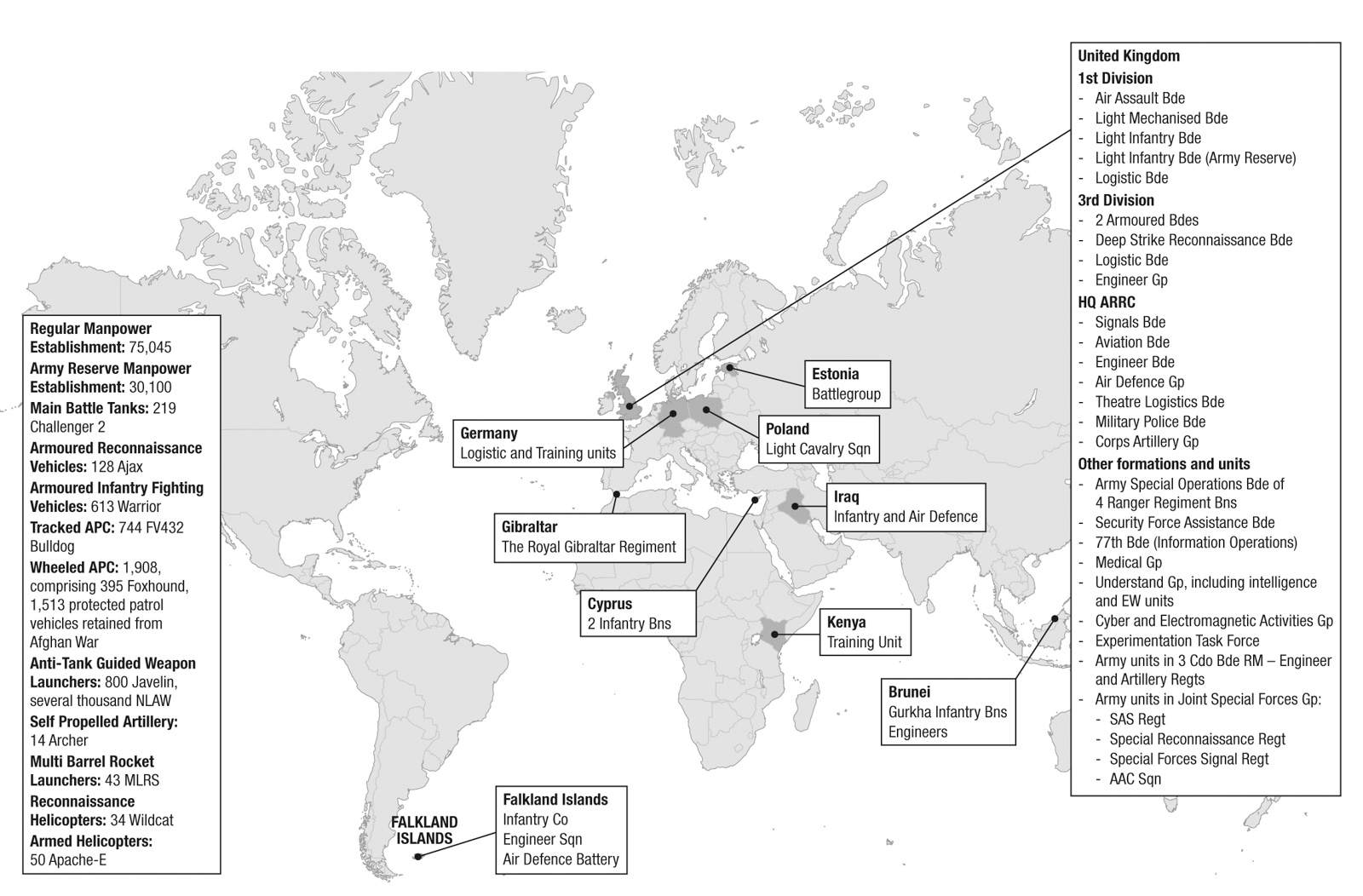

At the end of the Cold War in 1991 the Army had 155,000 troops in four divisions, with nine armoured and four infantry brigades. In 2025 it had 75,000 troops in two divisions, with two armoured and three infantry brigades. Combat power had shrunk by more than half. And the Army was less ready for war. Ill-prepared not just for a high-intensity war with Russia, but even for a more limited role as part of a potential Ukraine Reassurance Force.

Why did this contraction happen? The short answer is that defence reviews in 1991 and 2010 each directed the Army to cut a third of its manpower and equipment. Successive governments seemed content with the resulting military risks, whilst often denying that British military power was reducing.

Inadequate leadership by prime ministers Tony Blair and Gordon Brown and their rotating cast of defence ministers, led to avoidable casualties and strategic defeats in Iraq and Afghanistan, increasing the human, financial and reputational costs of both wars. This resulted in declining political, public and media support for putting British troops in harm’s way.

A lethal combination of Treasury hostility to defence spending and the Ministry of Defence (MoD) favouring investment in ships and aircraft continually squeezed the Army’s resources. To live within its budget the Army was forced to cut away the people, weapons, logistics and training that were so essential to military effectiveness.

HOW THE ARMY COPES WITH COMBAT AND CONTRACTION

The Army is commanded by the Chief of the General Staff (CGS), whose job is no sinecure. He has to obtain and sustain the confidence of the Defence Secretary and the Chief of the Defence Staff. This could be difficult, further complicated by senior MoD civil servants with agendas that diverged from the Army’s, particularly reducing costs whilst centralising authority away from the Army.

The job needs excellent communication skills, broad shoulders, the ability to think and lead strategically and to rise above the detail to concentrate on the really big issues, where he can make a difference.

It was essential to balance ends, ways and means over the short, medium and long term. The Army’s leadership was constantly seeking to do so, in order to achieve two things. Firstly, succeeding on operations. These are directed by the Prime Minister, National Security Council and Defence Secretary, on whose leadership and personal effectiveness much depends. Some, such as Margaret Thatcher, exhibited the necessary qualities, as did Blair over the Balkans and Sierra Leone, but his leadership of the Iraq and Afghan Wars was poor.

When wars became difficult, as they did in Iraq and Afghanistan, training and preparing formations for deployment and seeking to influence their employment to maximise the chance of success whilst minimising risk of avoidable casualties, became the Army’s top priority. Where the Army succeeded, it would demonstrate its utility.

The Army’s second priority was to safeguard its future, securing the necessary funding for its people, infrastructure, equipment and training. In this it was competing with the Royal Navy and RAF for a share of the defence budget, whilst the MoD competed with other Whitehall departments for the Treasury’s largesse.

The Army has a pragmatic and innovative “can-do” culture, which often produces great success on operations. But when the Army is given inadequate resources and direction it has a default setting of attempting to do what it’s been told to do to the best of its abilities. Many Army chiefs have sometimes wondered whether they should speak out and then resign. But their hands have been stayed by a deeply ingrained sensed of loyalty, upwards to the constitution and downwards to the Army.

These factors explain why over this period of successive reductions in defence spending, the Army judged that it had to accept government and MoD leadership, management and decision-making that it privately considered deeply flawed and damaging to its operational effectiveness.

THE GULF WAR, OPTIONS FOR CHANGE AND THE “NEW WORLD DISORDER”, 1991 — 1998

In 1990-91 the Army was tested by an unexpected mission: Operation Desert Storm to eject Iraqi forces from Kuwait. The 1st Armoured Division destroyed Iraqi forces faster and with fewer casualties than expected. Even with 34,000 troops in the Gulf, the Army still sustained its other commitments to NATO and Northern Ireland.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, John Major’s government wanted a “peace dividend”. The Options for Change defence review removed a third of the Army’s people and equipment, reducing the Army from four combat divisions to two and losing 22 infantry battalions and armoured regiments. The Defence Secretary, Tom King, claimed the Army would be “smaller but better”. Subsequent overstretch convinced some soldiers that King had left them “smaller but bitter”.

This was followed by the Treasury imposing more savings, cutting another 2,200 troops. Army medical services were cut and much of their peacetime training and employment assigned to the NHS. Military families’ housing was sold off to the private sector, a move that subtracted, rather than added value. This move has finally, belatedly, been reversed.

In the early 1990s the Army faced down brutal warlords in unanticipated and difficult UN operations in Bosnia. The 1996 NATO intervention saw the Army deploy over 10,000 troops to Bosnia, including the new British-led Allied Rapid Reaction Corps HQ, HQ 3rd Division, an armoured brigade, and combat and logistic support that joined the new NATO Implementation Force.

The Labour government’s 1998 Strategic Defence Review saw the Army re-organise to form new mechanised and air assault brigades. To improve deployability, the size of the Army was to increase by 3,300 logisticians, engineers and signallers. Two aircraft carriers and a new joint strike fighter were to be acquired for the RAF and the Royal Navy.

The MoD accepted a financial settlement with the Treasury that underfunded the implementation of the review by about £500m per year, insufficient for the announced future programmes. The Chancellor, Gordon Brown, was clear that his top priorities for spending were social welfare, reducing child poverty and funding international development and was unsympathetic to defence. This was recounted by the then Chief of the Defence Staff, then General Sir Charles Guthrie.

The strategic defence review was not the first time (nor was it the last) that I had to cross swords with the Chancellor Gordon Brown. We got off to a poor start. It was clear soon enough that Brown would not fund what had been previously agreed. When I went to see him at 11 Downing Street to discuss the review he paid no attention to what I told him.

It was not long before he interrupted and said with a smirk, “General, I do know a bit about defence you know.” I gave him a hard look and replied: “Chancellor, you know fuck all about defence.” His face turned red, and his jaw slackened …

I genuinely felt that the armed forces, and the Army in particular, suffered because of the damaging clashes between Blair and Brown. If I raised the topic of funding with Blair, he would look distinctly uneasy and just say “Well, you need to take that up with Gordon.”

In 1999 NATO bombed Serbia, attempting to stop Milosevic’s bloody repression in Kosovo. The Army rapidly deployed to Macedonia, in readiness to become the Kosovo stabilisation force, after any ceasefire deal. Whilst providing humanitarian support to refugees, they planned in conditions of great secrecy for a British-led corps-level ground attack on Kosovo and Serbia, which would have required 50,000 British troops, including a division and mobilisation of reserves.

Milosevic blinked first and Serb forces withdrew, supervised by NATO. The Alliance’s erratic command and control caused great friction, not least when supreme commander US General Wes Clark ordered the British to confront Russian troops at Pristina. The resolute and experienced British General Mike Jackson refused to obey this dangerous order, telling Clark that “I’m not going to start World War Three for you.” British troops were welcomed as liberators restoring security and essential services.

A rapid deployment to evacuate civilians from war-torn Sierra Leone defeated the vicious Revolutionary United Front rebels that were on the cusp of victory. After a daring mission by the SAS and the Parachute Regiment to rescue British hostages, a decade-long British initiative rebuilt the country’s army. The 9/11 attacks saw rapid deployment to Kabul to create the International Security Assistance Force, after which there was another enduring commitment in Afghanistan.

THE DEFENCE REVIEW THAT NEVER WAS, 2003-4

That the interventions in Iraq, Bosnia, Kosovo, Sierra Leone and Kabul all succeeded with few casualties showed that the Army had effective doctrine and was well trained and led. But success led to complacency, the MoD forgetting that in war the enemy gets a vote, and can fight to the death to cast it.

The Army constantly struggled to achieve the funding and manpower it needed and the MoD came under even greater financial pressure from the Treasury. A dispute between Defence Secretary Geoff Hoon and Chancellor Gordon Brown over budgetary rules of engagement ended in 2003 with Prime Minister Tony Blair ruling in the Treasury’s favour. This required immediate cuts to the defence budget, and a secret defence review by stealth.

The previously announced increase in troop numbers was quietly abandoned, and there were more cuts to personnel, units and armoured vehicles. Although not publicly declared at the time, money allocated to the future helicopter programme was greatly reduced. This meant that later operations in Helmand would have insufficient helicopter support, despite public denials by politicians.

In the decade between 1995 and 2005, the reduction of violence in Northern Ireland meant that the smaller Army could just about sustain these commitments. As the Troubles ended money was saved by reducing the size of the infantry, resulting in a radical re-organisation of its regimental structure.

IRAQ AND AFGHANISTAN

The two defence reviews between 1998 and 2004 had resourced the Army to conduct a single brigade-level “peace support” operation, along the lines of Bosnia or Kosovo. But by mid-2006, it was fighting two counter-insurgency wars. Combat was more intense than anticipated. The Army was operating well beyond the demands it was funded and structured to meet, with the resulting danger of being burned out by the pressure of these increasingly unpopular wars.

Despite some substantial tactical successes, weaknesses were displayed in both wars, many highlighted by the media. The Army’s and MoD’s Iraq lessons-learned reports identified that both organisations were too slow to adapt. The Iraq Inquiry was very critical of procurement of equipment for stabilising Iraq, including a lack of urgency and unclear accountability.

It assessed that delays in fielding improved surveillance, helicopter and protected patrol vehicle capabilities resulted in avoidable casualties. Over-centralised and inflexible MoD decision-making added friction and delay. The Army chief, General Sir Richard Dannatt, assessed that the MoD disempowered his leadership of the Army:

although charged with responsibility for the overall fighting effectiveness of the Army, today the CGS — as a result of the centralisation which so vexed me — owns so few of the decision-making levers pulled and pushed by his predecessors. Alanbrooke and Templer would have shaken their heads at my inability to determine and decide.

Dannatt saw his duty as meeting “an overriding need to get our message out more widely” to sustain public support for Army operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. He embarked on an MoD-approved programme of media briefings and public statements. This had welcome effects, including spontaneous commemorations of the fallen at Wootton Bassett, the energising of Help for Heroes and other charities, and civic events for units returning from operations.

But an October 2006 interview with the Daily Mail was spun as criticism of the Iraq War and government policy. The inconvenient truth was that Dannatt was doing a much better job at articulating MoD’s strategy for Iraq than the overwhelmed Defence Secretary Des Browne.

Geoff Hoon had served as defence secretary for six years, just two weeks short of the term served by Denis Healey. But after his departure there were four defence secretaries in three years: Des Browne, John Reid, John Hutton and Bob Ainsworth. In a time when the US had two defence secretaries, Donald Rumsfeld and Robert Gates, the UK had five.

Although Reid and Ainsworth had both served as ministers of state for the armed forces, it often seemed that Browne, who was also minister for Scotland, was not on top of his brief, particularly on Iraq and the Army. The Iraq Inquiry assessed that he displayed optimism bias.

It is probably wrong to simply blame Browne for this — the MoD itself sometimes showed institutional optimism bias during this period. Even after 2006, when the Air Chief Marshal Sir Jock Stirrup, the new CDS, gave clear direction that “we are in two wars, and we have got to win them both,” there were some UK defence organisations that displayed little sense of urgency.

In 2008, then C-in-C Land Command, General David Richards, placed the Army on a “campaign footing”. Operation Entirety made Afghanistan the Army’s main effort. This had significant impact on equipment, training and doctrine, leading to improvements in, for example, surveillance, counter-IED and medical support as well as mission preparation.

But the ruthless prioritisation of Afghanistan over all other missions meant that training and preparation for state versus state land war was neglected. Inevitably the considerable sums spent on the additional costs of Iraq and Afghanistan took money away from war-fighting capabilities. This was exacerbated in 2007 when the MoD’s top board agreed to fund two aircraft carriers and the stealth fighters to fly from them. The opportunity costs to the defence budget were borne, in part, by the Army’s future equipment plans.

Between 2006 and 2010 civil/military relations reached crisis point. Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s relationship with the senior military leadership had been gravely damaged by the cuts he imposed on the defence budget whilst he was Chancellor. He visibly struggled to reconcile supporting US strategy with a meaningful British military contribution and a British public, and parliamentary opposition, increasingly unsupportive of the wars.

Media criticism intensified over the handling of the wars in Iraq, reaching a peak in the Sun newspaper’s 2009 campaign: “Don’t they know there is a war on?” A crisis point was Operation Panther’s Claw in 2009, when a surge in casualties resulted in considerable media criticism. There was a loss of mutual confidence between MoD, Number 10 and the Army.

Serving in the MoD at the time, I saw for myself how some, but not all, parts of the MoD developed the necessary sense of urgency. Other parts resisted bending themselves out of shape and clung to a business-as-usual modus operandi. Between 2005 and 2012 this was not helped by the MoD permanent secretaries — the department’s top civil servants — coming from other departments. They sometimes appeared swamped by the size of Defence, its complexity and challenges. Military officers and MoD civil servants were unimpressed.

MORE STRATEGIC SHRINKAGE

In 2010, David Cameron’s new coalition Government improved the direction of strategy by forming a new National Security Council and setting an exit strategy for Afghanistan. But to reduce the economic damage inflicted by the 2008 economic crisis, it cut public spending. Conducted in great haste, its 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review cut the Army’s strength and capabilities by another third. Ministers proclaimed that the review had not resulted in strategic shrinkage. Nobody in the armed forces believed this.

The subsequent Levine Review of the higher management of defence proposed a delegated model that restored the service chiefs’ responsibilities for delivery of military capability and the formulation of equipment capability requirements that had been removed during successive waves of centralisation since 1998. The Army relished taking control of its finances, but this empowerment could not produce more money than the MoD was prepared provide.

And the MoD’s reputation was damaged by botched equipment procurements, such as the Astute submarine, A400M Atlas airlifter and Ajax scout vehicle. These all acted to reduce the amount of military capability that could be squeezed out of the defence budget. In the case of Ajax, an independent inquiry allocated blame equally between the Army, the manufacturer General Dynamics, and Defence Equipment and Support, the MoD’s procurement agency.

No one should pretend that procuring cutting-edge high technology weapons is easy, but successive efforts to reform military procurement are yet to bear fruit, much to the frustration of the Army and other services.

DEFEATS, STRATEGIC SHOCKS AND INCONVENIENT TRUTHS, 2021-25

The 2021 Integrated Review of Defence and Security had many innovative ideas, including the Army’s new Ranger Regiment, but further reduced Army size to 75,000 regulars and 30,000 reserves, cutting more combat capabilities — including the Warrior infantry fighting vehicle (above right) that had been so successful in Iraq, Bosnia and Kosovo. No other NATO army lacks such fighting vehicles.

NATO had ceased combat operations in Afghanistan, when British troops withdrew from combat roles. But in mid-2021 the Taliban were victorious — a strategic defeat for the US, NATO and the UK. The Commons Defence Committee called for a national inquiry into Britain’s war in Afghanistan. This was given a stiff ignoring by the government and the opposition Labour parties. Will this deliberate institutional complacency be the handmaiden of subsequent strategic defeats?

With the 2022 Russian attack on Ukraine having greatly increased the chances of war in Europe, there could be no more equivocation, or hiding behind soundbites, however carefully crafted by spin doctors. The MoD had to recognise the shortages of combat supplies and medical capabilities required to fight a high-intensity war. Readiness was further reduced by British weapons and supplies being sent to Ukraine.

Of the three British services, the Army was the least modernised, with much key fighting equipment either obsolete or approaching obsolescence. Royal Navy and RAF ships and aircraft are more modern than the Army’s armoured vehicles. And the greatly reduced land sector of the UK defence industry lacked the political support and influential lobbies of the shipbuilding and aerospace industries.

An early indicator was Operation Mobilise, Army chief General Patrick Sanders’ direction to the Army to improve its readiness for war. As with the 2008 Operation Entirety to urgently optimise the Army for the Afghan war, the implication is that if the MoD had been fully committed to supporting the Army, including providing adequate resources, Operation Mobilise would not have been necessary. That neither the Royal Navy nor the RAF conducted such an exercise confirmed that their readiness was greater.

THE STATE OF THE ARMY TODAY

Last year the Commons Defence Committee report “Ready for War?” uncovered shocking shortages of the ammunition, combat supplies and medical support necessary to fight a high-intensity war. Defence Secretary John Healey stated that, whilst the armed forces were able to conduct peacetime operations, such as evacuations, they lacked the necessary capabilities to fight a war.

For example, at the end of 1995, the Army deployed 10,000 troops to the NATO force enforcing Bosnia’s fragile peace. These were fully combat trained and well supported by logistic and medical units and supplies. It seems very unlikely that the Army could rapidly deploy a similar sized combat-capable force to any reassurance force in Ukraine.

Until these capability weaknesses are rectified, deploying British Army units and formations to fight carries increased risk of avoidable casualties. In a shooting war, these weaknesses would mean that British brigades would take greater casualties and be slower to achieve their missions than better equipped and trained US brigades. These factors are what most worry US generals who might have to fight alongside the British.

Failure to be able to “fight tonight” carries the risk of mission failure. After a defeat, the damage to the armed forces’ credibility would be such that the British public would lose confidence in their competence and value for money. The US, NATO and the UK’s allies and adversaries are all well aware of these weaknesses, not least from reporting by their attachés in London. This reduces UK military credibility and influence.

A LACK OF EXERCISES

Modern warfare is very complex. It requires synchronising the activities of the many components of a modern land force: tanks, armoured vehicles, infantry, artillery engineers, helicopters, drones and logistics. Just as sports teams need to take on demanding opponents, so armies need to train on realistic and challenging field exercises.

Throughout the Cold War the Army had made great efforts to do this, with battlegroups exercising with live ammunition for months over the windswept prairies of Suffield in Canada (BATUS). Whole divisions exercised every autumn in West Germany and Army units in the Royal Marines’ commando brigade spent long winters training in the Norwegian Arctic.

These were simulated battles in which tens of thousands of British troops manoeuvred. They allowed plans, tactics, deployment logistics and commanders to be tested. So, there was a real fog of war, friction and much pressure on commanders. Lessons were learned.

Many of those who served in the Falklands War observed that the Army’s high level of exercising had made a great contribution to success. Later commanders credited the Army’s success in Iraq in 1991 and 2003, as well as the Balkans, to the twin forges of training in Canada and Germany. Battlegroup and brigade training continued after the Cold War in Germany, Poland and Canada, sustaining the confidence and competence of those who deployed to the challenging operations in Bosnia, Kosovo and Basra.

But as the demands of Iraq and Afghanistan intensified, the Army’s training increasingly focused on “mission rehearsal” for operations there. As the Iraq war ended, battlegroup training at BATUS briefly resumed. But this unique training facility was closed during the 2020 pandemic and appears to have never re-opened. The Army said that training for heavy battlegroups would move to Oman.

Some battlegroup exercises took place, but the level of armoured warfare training in Oman was much lower than had been achieved in Canada. Although some brigades took part in NATO exercises, these, by their multinational character, were less demanding than those the Army had previously run for brigades in Germany, Canada and Poland.

Exercises are a key element of the Army’s military capability and credibility, particularly with the US military. After 2014, as it reduced its troops in Iraq and Afghanistan, the US Army resumed conducting demanding brigade-level field exercises. Ten armoured brigades a year rotate through the US National Training Centre at Fort Irwin and light brigades regularly train at the Joint Readiness Training Centre. In the same period, the British Army never achieved that level of training.

Why was this? It’s difficult to get a straight answer from the Army, but it seems that in the decade after 2014, the Army’s ever-contracting budget, troop numbers, equipment holdings and stockpiles of ammunition and spare parts made sustaining the training base in Canada increasingly difficult, resulting in the establishment having to close. This created a generation gap in expertise in armoured warfare.

From 2022 onwards the Army participated in increased NATO field exercises, including spending a year providing the lead land elements of NATO’s Very High Readiness Joint Task Force. For example, in 2024, it made a major contribution to NATO Exercise Steadfast, which brought together existing German and Polish national exercises under the NATO banner.

The Army sent some 16,000 troops, from 7th Light Mechanised Brigade, 12th Armoured Brigade, 16th Air Assault Brigade, 101st Logistic Brigade and the HQ of 3rd Division. Operations included seizure of an airfield in Estonia by a parachute battalion, followed on by air landing infantry, and river crossings in Poland by the armoured and mechanised brigades and British M3 ferries.

Mobilisation, movement and deployment provided useful validation of Army plans to deploy to Eastern Europe. And the brigade exercises practised multinational tactical interoperability. But having deployed a division’s worth of brigades, it was surprising that after the NATO exercises finished, the separate brigades did not come together on a European training area for a full British divisional exercise. I asked senior officers why this did not happen. I did not receive a convincing reply. It seems most likely that the Army’s reduced size and budget made it impossible to sustain the training. This was a stark illustration of the penalties of reduced budgets, manpower and equipment.

In early 2025 the Army conducted a brigade exercise for 4th Light Brigade, including two of its battlegroups, where the force was thoroughly tested against a demanding OPFOR (opposing force) on Salisbury Plain. This appeared to be the first such exercise for two decades.

WHAT IS TO BE DONE?

In 2025, the new Labour government conducted another strategic defence review and a modest increase to defence spending was announced. Military activity was to be guided by the principle of “NATO First”, although the government appeared content to send the Royal Navy’s aircraft carrier task force in the opposite direction to the Indo-Pacific, where it cruised as far away from Europe as it could.

In contrast, the Army relentlessly focused on NATO and Europe, reforging its links with the French and German armies, both of which were now larger. And the German and Polish armies have been given more money to rearm at a faster rate than the British Army. British military influence in NATO will decline as a result.

The Army was assigned a very challenging mission of providing NATO with a strategic reserve corps of two divisions. This requires it to be much more ready for war than it currently is. And to generate the force requires an Army of 90,000 troops rather than the current 75,000.

Army chief General Sir Roly Walker has set out a vision for radical change, increasing use of drones, artificial intelligence and deep strike weapons. And a modernisation of some equipment including the Apache helicopter and Ajax, Boxer and Challenger vehicles was funded. He intends that these initiatives should triple the Army’s lethality.

The defence review called for the Army to “increase lethality ten-fold”, but showed no evidence this was achievable. It seems more like optimistic spin than evidence-based assessment. Rather than entangle the Army’s future in hollow soundbites, the MoD should do everything it can to empower the Army and unleash the creativity, ingenuity and fighting spirit of its people. This would also promote retention and recruiting.

An exciting Experimental Task Force is exploring new ways of fighting with emerging technology. But important capability gaps remain, not least in infantry fighting vehicles, present in all other NATO armies. Without a significant injection of additional money, combined with ruthless pruning of a paralysing overgrowth of bureaucracy and red tape, it is not clear how the decline in the Army’s fighting power can be reversed.

The Strategic Defence Review promises a high-tech “integrated force”, ready by 2035. But the NATO secretary general and many European intelligence agencies assess that after any ceasefire in Ukraine, Russia could reconstruct its damaged forces in five years. If they are right, the Army needs to be modernised by 2030. So the top priority for this government’s parliamentary term must be making the Army able to “fight tonight”, requiring a much sharper short-term focus on making the Army ready for war, with the equipment it has now — not waiting with glacial slowness for a decade.

This needs rapid purchase of ammunition and spare parts from the defence industry, and the Army’s medical capability must be rapidly rebuilt. Army plans to field more drones should be accelerated. There is a vast thicket of risk-averse bureaucratic rules that frustrate realistic training, not only with drones, but also more widely. These should be ruthlessly cut.

All of this must be tied together and demonstrated by the Army conducting more field exercises at brigade level and above. The Reserves should be much more integrated with the Regular Army, especially its operational plans and exercises. This was achieved in the Cold War. It can be achieved again.

More than any glossy recruiting campaign, restoring readiness and increasing training and exercise levels would boost morale and confidence. This would improve retention and, as the word of the Army’s improving capabilities spread into the communities they come from, recruiting would also improve. And as Army readiness was restored the Army would continue planning and training to “fight tomorrow”.

The Army is not fully recruited. It has an authorised strength of 75,000 troops. In July 2025 it had 73,490 troops, a decrease of 810 troops since July 2024. There was a surge of applications in 2024 and 2025. Over 40 per cent were from the Commonwealth, a figure well in excess of the number of places available for Commonwealth recruits. The Army Reserve should have 30,000 people. In July it had 25,700, a decrease of 320 since 2024.

The independent Armed Forces Pay Review Body report of May 2025 judged that the services were facing a “workforce crisis”, with outflow well above average historical levels, with more people leaving the services than had joined over the previous year. A factor was the standard of accommodation provided for single and married personnel. The report said:

The provision of quality accommodation is an important element of the offer to Service personnel. On our visits we saw some good accommodation, but in many locations, we saw examples of Service Family Accommodation (SFA) and Single Living Accommodation (SLA) that were disgraceful. We note that the overall standard of maintenance has deteriorated since last year. We assess that if personnel are required to live in substandard and/or poorly maintained accommodation this fundamentally dilutes the value of the overall offer and is bad for morale.

It also judged that soldiers’ pay compared less well than it should with the pay of those in the civil sector. Many soldiers “were working alongside contractors who were undertaking similar or even identical roles for apparently higher rates of pay and often with a more manageable work-life balance”. The body approved an Army proposal for a retention payment of £8,000 to private soldiers and lance corporals. It is too early to tell if this has had any effect. Many experienced specialists could be much better paid outside the Army.

There are multiple reports of a significant number of troops being unfit to rapidly deploy on operations. This includes soldiers requiring dental treatment, a problem that could easily be solved by funding private dental care. In December 2024, junior defence minister Al Carns revealed that only 55,000 troops were fully fit to deploy at short notice. Given the apparently parlous state of military medical services, this is a significant weakness. It is not clear that the problem is being tackled with the urgency it deserves.

There is much rhetoric from the Army about exploiting new technology. Project Asgard is an ambitious initiative to create a “digital targeting web” linking surveillance systems to drones and conventional weapons, all enabled by artificial intelligence. This is now deployed in Estonia, and the Army hopes to soon conduct a live firing test exercise. And the Army is training soldiers to fly drones, using hundreds on exercises and is purchasing new attack drones.

But these plans will be of little avail if, in the near future, the Army failed in a war. Does the Army have the right weapons and equipment to “fight tonight”? The size of stockpiles of ammunition, fuel and spare parts is classified but analysis of exercises and operations over the last decade suggests that the Army probably has enough ammunition and spare parts for a light brigade to deploy and fight, but not enough for its armoured brigades and the heavy division of which they are part. And light forces have few if any armoured vehicles and are particularly vulnerable to attack by armoured forces.

This is why the Army retains two armoured brigades in the 3rd Division — the 12th and 20th. (Most NATO armies have armoured divisions with at least three armoured brigades.)

All the armoured brigades’ AS 90 medium self-propelled guns were donated to Ukraine along with all their ammunition. The 52 guns have been only partially replaced by 14 Swedish Archer guns, only enough for a single battery, rather than the four batteries required by a brigade. The aged CVR(T) Scimitar reconnaissance vehicles held by the armoured cavalry are obsolete.

Only one of four armoured cavalry regiments has received the replacement — the problematic and long-delayed Ajax scout vehicle. Many of the Warrior infantry fighting vehicles that should be with armoured infantry battalions have been issued to armoured cavalry regiments as a stopgap, pending Ajax’s arrival.

These issues were examined in the House of Commons Defence Committee 2024 report “Ready for War?” The committee wrote that “the UK’s armed forces require sustained ongoing investment to be able to fight a sustained, high intensity war, alongside our Allies, against a peer adversary”. The MoD has pledged to reverse these weaknesses, including investing £6bn in ammunition in this Parliament, including £1.5bn in an “always on” pipeline for munitions, and building at least six new ammunition factories in the UK. But the MoD is taking a long time to plan this initiative, with no evidence of any planning applications being made. There does not seem to be any indication that these declarations have yet provided any additional ammunition for the Army.

The government and MoD need to move faster and further, with greater urgency to rapidly rebuild the Army’s capability, halving the leisurely decade they have allowed for this.