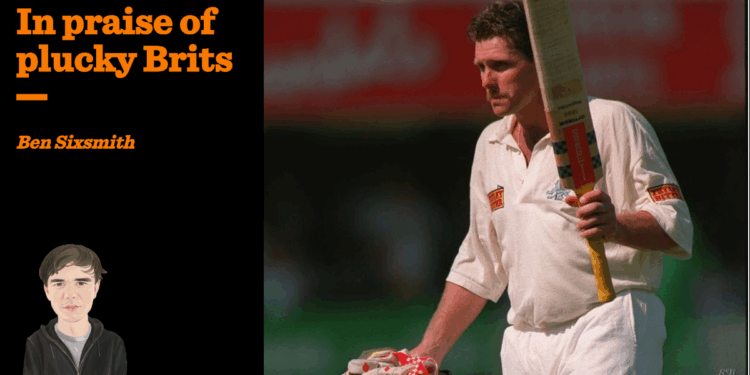

Robin Smith, English batsman and Hampshire captain, has died aged 62.

Smith — nicknamed “Judge” or “Judgey” — came from a different era of English cricket — an era where England were quite, quite bad. In a team where batsmen came, failed and went, though, Smith was a genuine success, averaging over 43 in Test matches.

Smith played in a time where English batsmen were often overwhelmed by fast bowlers like Malcolm Marshall of the West Indies or Terry Alderman of Australia. If the English line-up is fragile now, back then it was practically ethereal.

Cometh the hour, cometh the man. Smith was a strong, brave player who stood up to the might of the West Indies pace attack and defied the barrage on his stumps and head. (He was unusual in having a higher batting average against the West Indies than against other teams.)

In one innings, the ferocious Courtney Walsh hit Smith on the jaw and broke his finger. Smith kept batting.

Alas, the weak state of the English team throughout his career — he never played in a team that won a series against the West Indies or a match against Australia — means that Smith has been underrated. Now, England has all-time greats like Joe Root and Ben Stokes. Then, England had a class of men that I still think of as “plucky Brits”.

The plucky Brit is defined as much by their character as by their talents. The plucky Brit is an underdog — indeed, an underdog who rarely, if ever, prevails. But the plucky Brit still performs with bravery and honour. If nothing else, they can boast of moral triumphs.

English cricket was full of plucky Brits. There was the ageing pair of Brian Close and John Edrich — taking on a fearsome West Indian pace attack that included Michael Holding and Wayne Daniel. Close was covered in enormous bruises.

There was David Steele. Steele, a prematurely greying man that one journalist described as “a bank clerk who went to war” was an unassuming choice for a new batsman. Despite this, he stood up to Dennis Lillee and Jeff Thomson of Australia — one of the best fast bowling duos in history — and scored four fifties in an Ashes series. He became an unlikely choice for BBC Sports Personality of the Year.

Plucky Brits don’t have to be cricket players, of course. Michael David “Eddie the Eagle” Edwards came last in both of his events at the 1988 Winter Olympics but was loved for being an improbable yet enthusiastic participant. Tim Henman and Paula Radcliffe (who transcended her “plucky Brit” status by somehow becoming a dominant athlete) were examples of very good performers who, despite their best efforts, were not quite world beaters. “Come on, Tim” was meant to be encouraging but often sounded somewhat plaintive.

There was something sad about the celebration of plucky Brits. English and British sportspeople could not be expected to win — they were just applauded for doing their stubborn best. It’s tempting to suspect that this was influenced by a broader sense of British decline. Britain might have grown a lot less powerful, throughout the twentieth century, but it was still more virtuous than, say, swaggering Yanks (or, in sport, arrogant Australians). Britons remembered (at least until the final decades of the century) the doomed courage of Captain Scott. Britons remembered the innovative courage of Dunkirk. We could not be world beaters any more, perhaps, but we were plucky Brits damn it.

We expect more from our sportspeople nowadays. The 2012 Olympics proved that Britain was actually capable of producing gold medal winners who weren’t named “Steve Redgrave”. Since the 2005 Ashes, we actually expect English cricket teams to win rather than just being valiant in defeat. England even had a sniff of World Cup success.

Quite right. Sport is about winning. Britain should be expecting more from itself — not just in sport but in political, economic and cultural terms. At least in some areas of society, decline has been a choice — a product of complacence, oikophobia and overregulation. Here, the concept of the “beautiful loser” can be damaging.

Sometimes, amid decline, one can only make the most of one’s circumstances

Still, this was not the fault of a Close, or a Steele, or a Smith. Sometimes, amid decline, one can only make the most of one’s circumstances — maximising one’s abilities and refusing to succumb to anxiety or despair. When Brian Lara scored a dominant 375 in St John’s in 1994, England could have crumbled against the mighty duo of Courtney Walsh and Curtly Ambrose. Smith strode out and scored 175.

Smith had a difficult life after his retirement, dealing with alcoholism and depression. (Tragically, according to a recent Times interview, he was just about to meet his first granddaughter.) Still, we can all follow Smith’s example as a player — to stand up to intimidating odds and do one’s best.

After all, however difficult life can get, few of us have to withstand anything quite as ferocious as a bouncer from Courtney Walsh.