Predicting the future isn’t easy and perhaps it would be better if economists stopped trying. But thanks to the successive governments’ policy of borrowing up to the very limit of what the bond markets will tolerate, the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has assumed an importance in policy-making that is greatly disproportionate to its competence. This has led to the surreal situation in which the Chancellor of the Exchequer spends Budget Day solemnly talking about a decimal point here and a decimal point there in projections of what the economy will supposedly be doing in 2030/31.

The OBR has an impossible job and it does it badly. The right complain that neither the OBR nor the Treasury factor in the dynamic effects of tax rises and tax cuts while the left complain that they don’t factor in the multiplier effects of public spending. The right have a stronger case because the OBR does indeed take a quasi-Keynesian approach. As David Smith reported at the start of this year…

In most economic models, higher public spending boosts the economy more than the tax rises needed to pay for the spending reduces it. In the long run, of course, high taxes can damage economic growth. The OBR’s budget time forecast was for a range-topping 2 per cent rise in GDP this year, because of this higher public spending…

The OBR has since downgraded its growth forecast to 1.5 per cent but even that looks optimistic (the IMF forecasts 1.3 per cent).

Some dynamic effects — which is to say, changes in people’s behaviour — are fairly predictable. Steep rises in tobacco duty in recent years have led to a booming black market which is obvious to everyone except HMRC (of whom more in a moment). Recent rises in alcohol duty have led to some people drinking less, although it has conspicuously failed to reduce the number of people dying from alcohol-related causes. Tax revenues from both alcohol and tobacco have fallen since 2021 despite tax rates rising. This is the much-maligned Laffer Curve in action and it took the OBR by surprise.

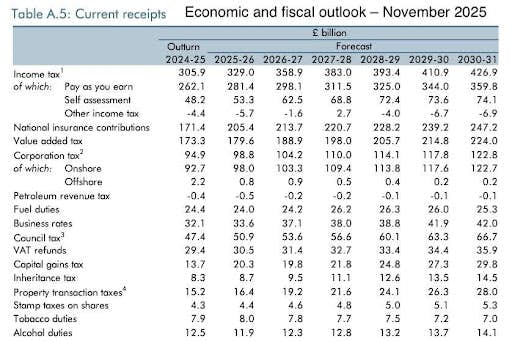

In last week’s budget, it was quietly announced that tobacco duty will once again rise by inflation plus two per cent and alcohol taxes will rise by the rate of inflation. As usual, the OBR modelled the effects of this. Bearing in mind that tobacco duty revenue fell from £10.2 billion in 2021/22 to £7.9 billion in 202425, and that illicit cigarettes are available for a fiver or less to anyone who is prepared to make the slightest effort, you might think that the OBR would be forecasting a further decline in the tax take. But no. It heroically predicts that tobacco duty receipts will “raise £8 billion in 2025-26, a 0.8 per cent increase relative to 2024-25, as the increase to duty rates offsets reductions in consumption”. The OBR does accept that revenues will start falling in 2026/27 “in part due to the substitution from tobacco products towards vaping”, but not as sharply as they have been falling recently and it does not mention the illicit trade as a factor.

By contrast, the OBR thinks that alcohol duty receipts will fall this financial year before rising year-on-year until at least 2030/31. It thinks that alcohol consumption will fall by 6.4 per cent this year and then hold steady, with more alcohol tax rises leading to more alcohol tax revenue. It puts this down to “a combination of factors such as a growing trend of alcohol moderation, with substitution to no- and low-alcohol alternatives, and a response to higher prices”.

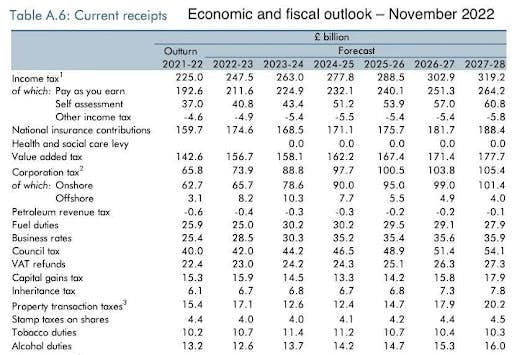

Maybe they are right about alcohol consumption. Probably not, but I wouldn’t necessarily bet against them. Forecasting is difficult, as I say. All I can say with confidence is that their track record is woeful. Compare the figures for alcohol and tobacco duty in the table above with their forecasts from 2022 below.

Three years ago, we were told to expect £11.2 billion of tobacco duty and £14.2 billion of alcohol duty. We actually got £7.9 billion of the former and £12.5 billion of the latter, a shortfall of £5 billion, the same amount the government would have saved if it had pushed through its welfare reforms. £5 billion was described as a “black hole” when those welfare reforms collapsed. It is the equivalent of twenty sugar taxes or ten family farm taxes. It is serious money and a reminder that when people buy less alcohol and tobacco, non-drinkers and non-smokers have to pay more tax.

The OBR’s figures were not wrong because the government threw a curve ball in the meantime. Under both Sunak and Starmer, alcohol duty and tobacco duty went up as forecast. People just changed their behaviour more than the OBR expected — which, in the case of tobacco, meant people switching to the black market.

Even a year ago, the OBR was miles off target with its prediction for 2024/25, forecasting tobacco duty revenue of £8.7 billion, an overshoot of £800 million. In March, when the financial year in question had nearly ended, its forecast was still £500 million off! And yet we are now supposed to believe that hiking the price of tobacco will not have the same effect on tax revenue as it has had every year since the pandemic?

It doesn’t help that the OBR is being given duff information about the size of the black market from HMRC. As I have said several times before, it is a mathematical impossibility for illicit tobacco to make up only 13.8 per cent of the total market, as HMRC claims. The number of cigarettes sold legally fell from 23.4 billion to 14 billion between 2021 and 2024 — a drop of 40 per cent — and the amount of hand-rolling tobacco sold legally fell from 8.6 million kilograms to 4.5 million kilograms — a drop of 48 per cent. At the same time, according to the ONS, the total number of smokers fell by 20 per cent, from 6.6 million to 5.3 million. In other words, legal tobacco sales have been falling at more than twice the rate as the number of cigarettes being smoked. It is blindingly obvious that the black market has picked up the slack.

I contacted the Office for Statistical Regulation (OSR) about this anomaly. At first I was told that there was nothing to worry about because tobacco tax receipts had “decreased broadly in line with overall UK consumption”, with both tax revenue and the number of smokers falling by around 20 per cent. But this is a red herring because tobacco taxes have risen enormously. HMRC’s own figures show that the tax rate on cigarettes has risen by 37 per cent since 2020 (not including last week’s increase) and the tax rate on hand-rolling tobacco has risen by 76 per cent. There has also been a great deal of inflation. The fact that tax receipts have fallen sharply despite a big increase in taxes and prices is further evidence that something is very wrong.

Even if you assume that there were no illicit tobacco sales in 2021, the data since then shows that they must now make up 28 per cent of the market, twice as much as HMRC claims. And since there clearly was a black market for tobacco in 2021, the true figure must be even higher. When serious attempts are made to gauge the size of this market by collecting discarded cigarette packs, they find that a quarter of manufactured cigarettes in the UK are illicit, and there is no doubt that the proportion of hand-rolling tobacco sold illegally is much higher (as even HMRC accepts).

It would be better to have no statistics at all than to have bad statistics

When I pointed this out to the OSR, I was told that “you make some good points” and that they “will ask HMRC to explore ways to use its statistics bulletins to address the issue of whether illicit use is growing (and therefore a bigger tax gap) more directly than it does at present.” They said that they will “also ask HMRC to continuously monitor whether its methods are optimally capturing tax gap and market size information, and what other ways they can assure the quality of the output(s).” Whether this will make any difference, I can’t say, but the regulator is at least aware of the problem and has recently announced a review into the quality of HMRC’s statistics.

It would be better to have no statistics at all than to have bad statistics. The OBR’s projections are baloney and HMRC has its head in the sand. In the absence of reliable estimates, we should work on first principles. Do extortionate taxes drive people to the black market? Yes. Has that happened with tobacco in Britain? Obviously. Will further tax rises make the problem worse? Almost certainly.