A presidential candidate in Honduras backed by President Donald Trump is leading the preliminary count to become the Central American nation’s next leader, scrambling a narrative about the U.S. war on drugs that the Trump administration has pushed in recent months.

The United States has carried out more than 20 military strikes on alleged drug-trafficking boats off the coast from Venezuela this fall in the name of unseating an authoritarian leader who the U.S. says heads up a narco-terrorist operation. Yet Mr. Trump last week made endorsements and pledges in Honduras that seemed to contradict those goals.

Mr. Trump endorsed Nasry “Tito” Asfura of the conservative National Party just days before the election, saying the two could work together to combat drug trafficking. Two days later on Nov. 28, Mr. Trump pledged to pardon former President Juan Orlando Hernández, a member of Mr. Asfura’s party, who was extradited to the U.S. in 2022 and sentenced to 45 years in U.S. prison, convicted of drug trafficking. At the Manhattan-based trial, the U.S. prosecutor said Mr. Hernández as president of Honduras had boasted that he and his collaborators were “going to shove the drugs right up the noses of the gringos.”

Why We Wrote This

President Donald Trump has vowed to attack drug trafficking across Latin America. But in promising to pardon a convicted trafficker from Honduras, he has swayed politics and unsettled policy.

The incongruity of chasing and attacking alleged drug traffickers in the region, at the same time that a powerful political player convicted of these very crimes is promised a U.S. reprieve, points to political and ideological motivations by the Trump administration, experts say, rather than a security plan.

“There is a strategy from the White House to consolidate the right in the western hemisphere,” says Lester Ramírez, a Honduran political analyst who teaches public policy at the Central American Technological University in Tegucigalpa. “It’s about creating a hegemony of the right.”

Tipping the scales

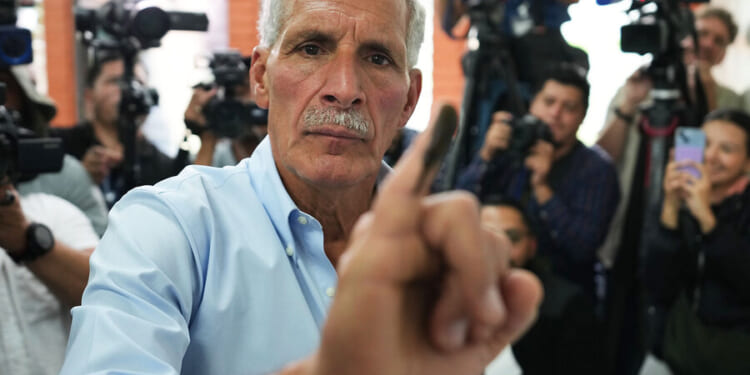

With just over 57.3% of votes counted by Monday afternoon, Mr. Asfura, a former mayor of Tegucigalpa, has 39.91% of the vote. He’s closely trailed by populist candidate Salvador Nasralla (39.89%) from the Liberal Party, and Rixi Moncada from the ruling LIBRE party has garnered 19.86% of the vote. The difference between Mr. Asfura and Mr. Nasralla is just 515 votes. There is still a chance that Mr. Nasralla could emerge as the next president.

In a flurry of social media posts last week, Mr. Trump called Ms. Moncada a “communist” and Mr. Nasralla a “borderline communist.” He painted Mr. Asfura, referred to as Tito and Papi colloquially here, as “the only real friend of Freedom in Honduras.”

Mr. Trump’s comments came after official campaigning ended.

“Of course it tipped voters,” says Mr. Ramírez. Before the U.S. endorsement, Mr. Asfura was polling several percentage points behind Mr. Nasralla. “It helped Tito’s image and the National Party’s ability to say, ‘We are close with the U.S., and if you vote for us, the country will be benefited by Trump’s new policies toward Honduras.’”

Gisselle Wolonzy, co-founder of Centuria, a Honduran political consulting firm, says that drug trafficking taints politics across the spectrum in Honduras.

All three political parties in the presidential race this year have alleged links to drug trafficking, she says. The brother-in-law of outgoing President Xiomara Castro resigned from Congress after a video emerged allegedly showing known drug traffickers offering him money.

When Mr. Hernández was extradited 3 1/2 years ago, Hondurans took to the streets in celebration. But he still finds supporters today. Iris Sevilla sat at the entrance of a polling station Sunday with a plate of pupusas on one leg and her 2-year-old daughter on the other. She voted for Mr. Asfura and says she’s unfazed by the pardon promised to Mr. Hernández. “Even if Juan Orlando was like that … it doesn’t matter if he was a drug trafficker,” she says. “When people were in trouble, in poverty, he helped them.”

In recent months, Mr. Trump has justified boat strikes and a U.S. military buildup off the coast of Venezuela, where authoritarian leader Nicolás Maduro was recently labeled the head of a narco-terrorist organization, in the name of fighting drug trafficking, says Eric Olson, senior adviser to the Seattle International Foundation, a human rights and democracy advocacy organization focused on Central America.

At face value, pardoning a proven drug trafficker, convicted in U.S. courts as was Mr. Hernández, doesn’t fit that larger narrative. But, “if you listen to [Mr. Trump] carefully, he says that the trial against Juan Orlando was manipulated by Joe Biden, his eternal political enemy,” Mr. Olson says.

President Trump “sees this as something ideological,” Mr. Olson says. The Hernández trial was “a political operation by the left and not legitimate. There is no evidence of that, but that is how [Mr. Trump] sees it, so he concludes that Juan Orlando is not a drug trafficker and is a right-wing person.”

In endorsing Mr. Asfura, he also wrote that the two would “work together to fight Narcocommunists, and bring needed aid to the people of Honduras.”

Communism has reemerged as a boogeyman in Latin America in recent years. Ms. Castro, in office since 2021, has strengthened the country’s relations with Cuba and Venezuela, both of which are sanctioned by the U.S. and are experiencing deep economic crises and political mismanagement.

U.S. interests in the region right now do have “more to do with the left versus right,” says Ms. Wolonzy.

Political alignment

Many here view voting for Mr. Trump’s pick as a pathway toward reversing U.S. policies that hurt Hondurans, says Mr. Ramírez. That includes record deportations and the recent cancellation of temporary protected status, which put an estimated 70,000 Hondurans at risk of deportation from the U.S. Many Hondurans rely on remittances from the U.S., which made up nearly 26% of the country’s gross domestic product in 2024.

There is also a strong evangelical, conservative base in Honduras that aligns with Trump administration policies.

The outgoing government has cooperated with U.S. deportations, receiving roughly 13,000 more Honduran deportees so far in 2025, compared with last year. Honduras is also host to a decades-old U.S. military base.

“If Asfura wins, it will be due to Trump’s endorsement. That could compromise him and his party,” says Ms. Wolonzy. “When a president like Trump formally endorses you to the world, there’s a certain pressure to follow his plan,” she says, even though exactly what the U.S. will be asking for from Honduras is unclear.

Given that, she’s keeping her eye on social media: There might be another message from Mr. Trump, she says, that indicates where the country may be heading.

Whitney Eulich reported and wrote this story from Mexico City. Yuliana Ramazzini Montepeque reported from Tegucigalpa, and Audrey Thibert contributed reporting from Boston.