This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Georges de La Tour, one of the greatest painters of the seventeenth century, is an enigma. The wonderful exhibition of La Tour’s paintings currently on show at the Musée Jaquemart André in Paris doesn’t solve that enigma — which may be because so little is known about him.

After the document acknowledging his baptism on 14 March 1593, he drops out of the record until 1616. By then he was 23 and a fully-fledged artist with a studio of his own. No one knows where he trained or to whom he was apprenticed, let alone how he learned to paint candlelight in such an extraordinarily luminescent way. No other painter, not even Honthorst or Joseph Wright of Derby, ever captured the exquisite mysteries of candlelight in the way Georges de La Tour did.

Exactly how he managed it is unclear. He might have travelled to Italy as a young man and seen some of Caravaggio’s pictures in Rome. Or perhaps he could have gone to the Low Countries and seen candlelit pictures by Dutch artists such as Hendrick ter Brugghen or Gerard van Honthorst. But there is nothing that proves he did so. Many art historians have nevertheless concluded from the evidence of his paintings that he must have been to Italy or the Netherlands. Others don’t agree. As with so much about him, the absence of documentary evidence means the dispute cannot be resolved.

La Tour didn’t paint portraits of rich merchants or aristocrats as almost every other major seventeenth-century artist did. It was the surest way to make money as well as a reputation, yet La Tour seems never to have tried it. Why not? No one knows.

Perhaps the artist, who was desperate to achieve aristocratic status, resented the position of subservience that painting the portrait of a rich patron would inevitably force him to adopt. Though he sold his paintings to dukes and to religious and civic institutions, the only patron from whom he accepted commissions seems to have been the King of France.

He married a minor member of the aristocracy and tried to persuade the authorities that his wife entitled him to aristocratic status. He spent a great deal of effort to get himself ennobled. He failed; though other artists of his generation from Lorraine were elevated to the aristocracy, he never was.

We know about La Tour’s doomed attempts to join the ranks of the aristocracy because it is one of the few topics mentioned by the surviving documents which refer to the adult Georges de La Tour. This primary evidence says very little about his pictures other than recording the prices of some them — which has simply made the fog of mystery surrounding him thicker.

There is continuing debate about whether all of the pictures attributed to him actually are from his own hand. The matter of his authorship is made all the more difficult because he often didn’t sign and date his work. Many copies of his paintings were made whilst he was alive and whilst most of the copies are clearly inferior in skill to the works of the master, some are not.

Furthermore, despite his success during his lifetime, La Tour the man was soon forgotten after his death. But his pictures were not forgotten: they were attributed to other artists. Velazquez, Murillo, Ribera and Zubaràn have all been credited with pictures now attributed to La Tour.

It was not until the early twentieth century that La Tour the painter was rediscovered. The man responsible was Hermann Voss, a German art historian (and later the curator of Hitler’s collection of looted art). Ever since Voss identified La Tour as the artist who painted The Newborn, connoisseurs and scholars have been arguing about which pictures are genuine La Tours — and which are 17th-century copies or even 20th-century fakes.

There is mystery, too, about La Tour’s personality and whether it related to his art. He was born in Lorraine and lived through a period of extraordinary violence there. The Thirty Years’ War started in 1618 and arrived in Lorraine in 1632, with the invasion by Louis XIII and Cardinal Richelieu.

The Duchy of Lorraine was then independent of France and nominally under the control of dukes who answered to the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperors. Lunéville, the small town in Lorraine where La Tour lived with his wife and ten children, was sacked and burned by French troops, who proceeded to ravage much of the countryside, robbing, raping and murdering wherever they went.

The appalling suffering of the civilians was made worse because disease and famine followed in the wake of war. According to some estimates, Lorraine lost more than half its population. La Tour lost his wife and seven of his ten children to varieties of disease. He himself would die of plague aged 58 in January 1652.

Where in La Tour’s work is the cruelty and brutality that caused so much suffering in Lorraine? Surprisingly, it never appears. On the contrary, many of La Tour’s paintings convey a mysterious sense of calm, peace and love. His depiction of St Sebastian — whose bloody martyrdom was a favourite topic of artists both before and after La Tour — is gloriously serene, with Irene gently ministering to his wounds as she contemplates the single arrow that has bloodlessly pierced Sebastian’s body.

Even the picture which is traditionally referred to as Musicians Fighting does not convey violence or even the threat of it. The musicians seem to be playing rather than brawling. As for The Newborn, La Tour’s picture of a young woman with a new-born child in her lap with an older woman looking on (assumed to represent the Virgin with Christ and St Anne), it transports you into a wonderful candlelit world where everything seems to be secure and nothing can intrude on permanent tranquillity.

The contrast between the beautiful, placid atmosphere that characterises many of La Tour’s paintings and the ugly brutality of the events through which he lived represents yet another aspect of the enigma that envelops him. The relation between an artist’s life and their work is never straightforward, but in La Tour’s case, the tension between the life and the work is particularly acute.

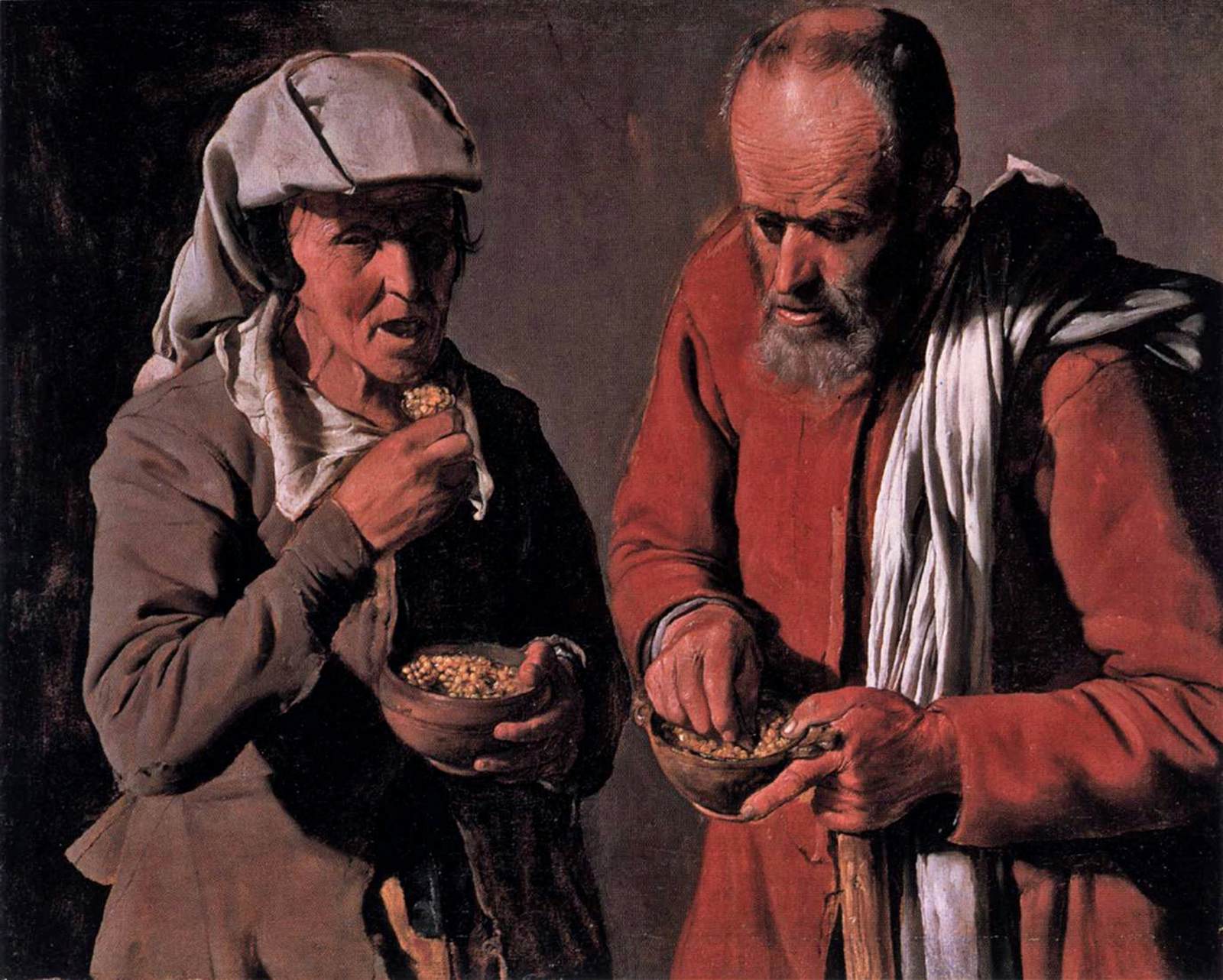

It is certainly not true that he was indifferent to other people’s suffering. Some of his most affecting pictures depict it. The Pea-Eaters is a meditation on two old people who have lost almost everything except their dignity. They are dependent on charity, and their wrinkled faces and hands are etched with their misery. La Tour does not condemn, patronise or judge them. He portrays them as victims of circumstance. Behind their sad, shabby exteriors, their basic humanity marks them out as our equals.

The same is true of La Tour’s pictures of a blind hurdy-gurdy player, of a peasant and of a blind old man with his dog. Artists had depicted such people before but usually as objects of derision or contempt. Without ever glossing over or minimising their pitiable condition, La Tour paints them as individuals who have a soul and who, behind their rags and their disabilities, are no different to us. We are only one piece of bad luck away from sharing their condition.

Whilst La Tour the artist’s pictures are full of sympathy for the suffering of his fellow creatures, the behaviour of La Tour the man was not. The year before he died, he flew into a rage and beat a ploughman named Louys Fleurette so badly that the poor man had to have extensive treatment from a surgeon.

Fleurette launched a complaint, which Georges de La Tour’s son Etienne settled for his father by paying the injured man’s legal and medical costs, awarding him compensation of 140 francs. (It was a substantial sum. For comparison: in his lifetime, La Tour’s most sought-after pictures sold for 700 francs.)

This wasn’t the first time Georges de La Tour attacked an apparently blameless citizen of Lunéville. He beat up an official who visited La Tour’s home to collect taxes he owed, then did the same to the next official who arrived. He attacked Bastien Drouin, another resident of Lunéville, for reasons that aren’t recorded.

La Tour knew how “to seek power and follow it”. It was not one of his most attractive characteristics. When the French invaded, he quickly abandoned the local officials of Lunéville whom he had known for most of his life and attached himself to the French invaders. He became friends with the governor imposed on the town by the French and, later, made him godfather to one of his children. He managed to wangle an invitation from Louis XIII to visit Paris. The visit was a great success: the King loved the painting La Tour offered him — it may have been of Saint Sebastian and Irene — paid him well and commissioned more work from him, granting him the title of “Painter to the King”.

He may have been a hit with French royalty, but he was widely hated by the residents of Lunéville, not least for hoarding grain during a time of famine and feeding his own dogs — he had many of them — rather than distributing his surplus food to starving neighbours. He refused to pay the special taxes levied to fund the rebuilding of Lunéville and to provide emergency help for the hungry and the indigent.

La Tour claimed that his wife’s noble status meant he was exempt and that, in any case, painting was a noble art — so as a painter, he was noble and so exempt anyway. The courts disagreed. They held that his wife was indeed exempt from tax, but the exemption did not hold during wartime. They dismissed his claim about the nobility of painting. La Tour had to pay his share.

What was behind La Tour’s egregious behaviour? Probably nothing more than an attachment to crude self-interest — an attachment so strong that it blinded him to the obvious suffering of the people all around him. But his eyes were opened to that suffering once he picked up his brushes and got behind an easel.

The magnificent painting entitled Job Mocked by His Wife demonstrates very clearly La Tour’s capacity to empathise, at least in paint, with the misery of others. It depicts a very old, almost naked man, crouching pitifully, as if awaiting yet another blow, in front of the huge figure of his much bigger and much younger wife, who towers over him.

An even more affecting example of La Tour’s capacity to recognise suffering and engender pity for it is The Tears of St Peter. This stunning picture represents Peter, the rooster next to him, as he realises that he has done exactly what Christ told him he was going to do: he has betrayed Christ. Peter’s expression captures perfectly a mixture of remorse, incomprehension and inconsolable sadness. Peter doesn’t understand how or why he could have betrayed Christ, the man he believes to be God. He only knows that he has done it. He desperately needs forgiveness. But he cannot forgive himself.

The show at the Musée Jacquemart exhibits 30 out of the 40 surviving pictures thought to have been painted by Georges de La Tour. But some of La Tour’s greatest works are missing. The Louvre, which has several, refused to lend any of them. So if you want to see de La Tour’s Joseph the Carpenter with the child Christ, for example, you will have to walk across Paris to the Musée du Louvre.

Exhibitions devoted to Georges de La Tour are rare. London has never had one, and the last one in Paris was nearly 30 years ago. La Tour’s pictures are excellently hung at the Musée Jacquemart André, but there is a problem. The curators have chosen to show the paintings in a series of very small rooms and hundreds of visitors to the hugely popular show are crammed into those tiny spaces, which are sometimes so crowded that it is almost impossible to get through the people to see the pictures.

Still, the struggle is worth it. La Tour’s paintings, especially the ones that depict scenes lit by candles, reproduce badly. Photographs cannot capture the amazing nature of the light that diffuses through those pictures, magically imbuing people and objects with cosmic significance. If you only know La Tour’s work through reproductions, you are in for an astonishing surprise when you encounter the real thing.

Georges de La Tour: From Shadow to Light is at the Musée Jacquemart André, Paris, until 25 January 2026.