Lori Lober is a busy woman. Her Facebook shows a life spent watching American football with her girlfriends, drinking cocktails on exotic holidays, and going out for dinner in Kansas City, Missouri, with her husband John.

‘Every morning, I wake up and thank God for another day,’ says the former interior designer. ‘And then I spend as much time as possible with my loved ones.’

Lori’s life may seem like a retirement dream, but it’s one she never takes for granted. Because nearly 25 years ago, at just 38, Lori was diagnosed with terminal breast cancer and told she had only a 2 per cent chance of living for five more years.

‘The doctors led me to believe I was never going to reach 40,’ she says. ‘The cancer had been missed for three years. By the time they found it, it had spread throughout my body.’

Today, however, Lori is 62 and cancer-free. She believes her miraculous recovery is due to an experimental cancer vaccine she received in 2002, alongside eight other women with advanced breast cancer and very few other treatment options.

Now, The Mail on Sunday can exclusively reveal that a 20-year follow-up of the trial set to be published next month will show that all nine women are alive and with no sign of the disease. It’s an extraordinary outcome.

While statistically unlikely that just one woman diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer would survive for another two decades, the chance that nine such women could is estimated at roughly one in 63trillion.

Experts say that vaccines such as the prototype received by these women are the future of cancer treatment.

Lori Lober is now cancer free at the age of 62. She believes her recovery is due to a vaccine she received in 2002 alongside eight other women who also had advanced breast cancer

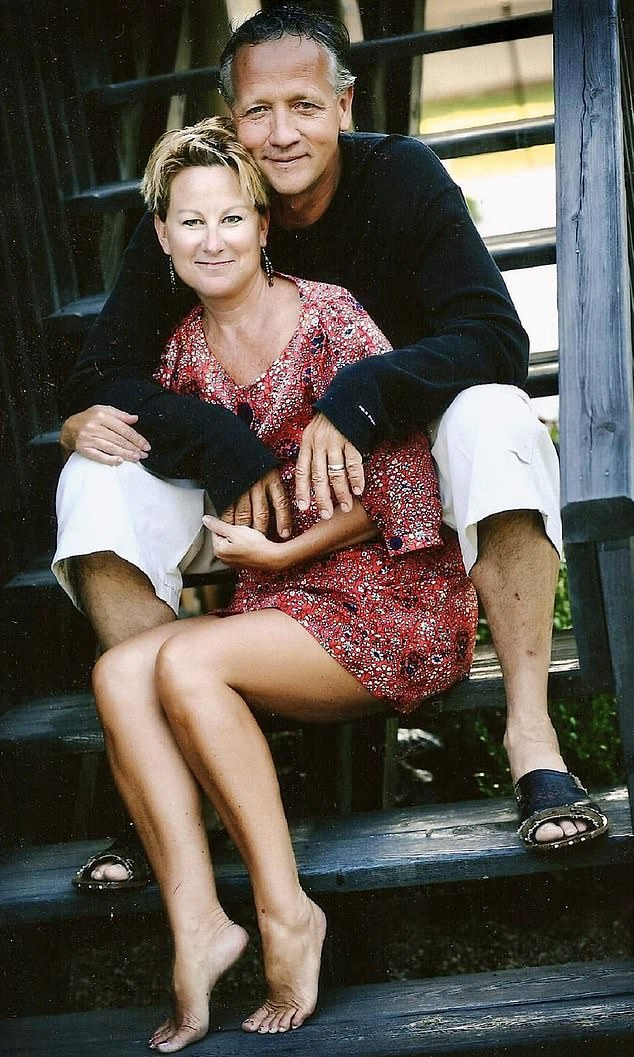

Lori with her husband, John. The American was diagnosed with breast cancer when aged 36

She is now thriving, enjoying a busy lifestyle which includes watching American football

Until recently, cancer vaccines were considered, among researchers, a pipe dream – even the stuff of science fiction. However, in the past five years alone, thousands of British patients – and countless more around the world – have received vaccines for lung, skin and ovarian cancers as part of landmark trials. And within just five years or so, it’s possible that some could even be available on the National Health Service.

But, crucially, experts believe the decades-old vaccine given to Lori may hold the key to boosting the effectiveness of all cancer jabs in development – potentially paving the way for a cure for aggressive forms of the disease.

‘Studies like this show vaccines do work for cancer,’ says Dr Lennard Lee, associate professor at the University of Oxford and a cancer vaccine expert. ‘These women show if you can activate a person’s immune system to fight cancer, it can stay active for decades.’

The need for new cancer treatments is clear.

Cancer mortality rates have fallen by over a fifth since the 1970s, and advancements in surgery and radiotherapy, as well as new immune-boosting and chemotherapy drugs, mean that patients are twice as likely to live ten years or more after diagnosis.

However, in the same period, the number of people developing cancer has risen by almost 50 per cent, largely due to an aging population and increase in rates of obesity.

For some cancers – such as pancreatic and brain cancer, which tend to only be diagnosed once they’ve already spread – very little progress has been made.

But now experts believe vaccines could be the key to reducing deaths from all cancers.

‘People may be incredulous that you can vaccinate against cancer,’ says Dr Serena Nik-Zainal, professor of genomic medicine at the University of Cambridge and a scientist at Cancer Research UK. ‘But the idea is that one day we won’t see the type of mortality associated with cancer right now.

‘Vaccines could allow cancer to become more like diabetes – something that people can just live with. And we think this can happen in our lifetime.’

Unlike traditional vaccines, which prevent diseases from taking hold by boosting the body’s ability to defend itself against foreign invaders, cancer vaccines aim to treat the disease after it’s occurred, by training the body to protect itself against its own damaged or abnormal cells.

Exposing the body to molecules associated with a specific cancer, these jabs effectively turbocharge the immune system to recognise and destroy cancer cells. It means that, should the cancer return, the immune system will spot it immediately and destroy the cells before they have time to spread.

It’s a project that’s been in development for decades, with plenty of false starts.

But in the past five years, progress has skyrocketed due to breakthroughs made during the race to find a Covid-19 vaccine.

So-called mRNA vaccine technology is at the heart of this advance – the same technology that is used in the Pfizer and Moderna Covid jabs.

Short for messenger RNA, mRNA is found inside cells: it’s the genetic code the body uses to produce proteins – molecules that form the building blocks of new cells, hormones, enzymes and other compounds.

In this type of cancer vaccine, man-made mRNA is injected into the body, programmed with codes that instruct it to produce specific protein molecules that prime the body’s immune system to fight cancerous cells.

It’s a technology that’s already been used to create a vaccine for deadly skin cancer melanoma – vital stage three trial results are expected to be published next year. And the world’s first trial of an mRNA lung cancer vaccine – called LungVax – was announced just last week, after years of research by scientists at Cambridge and Oxford universities.

However, these new treatments are unlikely to be slam-dunks.

In the case of the melanoma jab, early results suggest it can reduce the risk of death by 44 per cent. It also costs £400,000 per patient, making it potentially prohibitively expensive for the NHS.

Meanwhile, a prostate cancer vaccine approved for use in the US failed to get the NHS green light after officials decided its efficacy – reducing the risk of death by nearly a quarter – was not enough to justify its £70,000 per patient price tag.

For this reason, experts say the striking results from the Lori Lober vaccine study could prove significant in the hunt for a highly effective cancer jab.

The trial, which was carried out by Duke University, North Carolina, pre-dated mRNA technology. Instead, the researchers involved used something known as a dendritic cell vaccine, an older and more basic jab than mRNA, which uses the body’s existing cells to fight the cancer.

In the case of these nine participants, cells were removed from their bodies and then programmed to specifically target a protein in the body called HER2. For around a fifth of women with breast cancer, their body produces too many of these HER2 proteins, which encourage cancer cells to grow and spread much faster than normal.

By targeting this protein, the researchers theorised, they could slow, and more easily kill, the cancer cells.

In 2002, when the researchers, led by Dr Herbert Kim Lyerly, professor of surgery and immunology at Duke University, developed the vaccine, the process was so expensive they were only able to afford to trial it on nine patients.

All the women had advanced cancer and a very poor prognosis because it had spread throughout the body, making it near-impossible to cure.

Most women who are diagnosed at this stage live for no more than a few years, and often less.

The women went through standard breast cancer treatment, although each slightly differed in what they received – including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy and other experimental medicines. In Lori’s case, this had involved six months of chemotherapy before and after a double mastectomy.

Then, once as much of the cancer as possible had been removed, the participants were given the vaccine – a single dose injected into their arm. After this they took an immune-boosting breast cancer drug called trastuzumab once a month.

At the time, not many people believed the trial would actually work, according to Prof Lyerly. ‘People used to laugh at the idea of a vaccine,’ he says. ‘There wasn’t much enthusiasm about this approach at all.’

But, in 2007, a follow-up revealed all nine women were cancer-free. And now, 20 years later, all are alive and well.

It’s important to stress that the trial, given its small size, can’t prove anything more than an association between the vaccine and the women’s survival.

Medicines are almost always approved only after thousands of patients have taken part in what is known as a double-blind randomised control trial – the gold-standard for medical research.

However, experts say that the striking findings deserve close attention.

Prof Nik-Zainal describes the trial’s results as ‘incredible’.

‘Metastatic HER2 positive breast cancer patients are usually dead within five years,’ she says. ‘To see this result after 20 years is very impressive.’

However, experts say perhaps the most significant finding from the trial occurred when the blood from the nine women was examined, and they all had sky-high numbers of a specific type of immune cell, called CD27.

This has been historically overlooked in cancer vaccine research, says Prof Lyerly. Instead, most vaccine trials have focused on boosting CD8 immune cells, which hunt down and kill tumour cells. By contrast, CD27 cells, are ‘helpers’, meaning they simply assist the killer cells in finding the cancer.

But CD27 cells could be even more crucial to producing a long-term immune response, the Duke team hypothesised.

To try to prove this, researchers gave mice a dendritic cell breast cancer vaccine.

They then injected them with CD27 antibodies to boost their immune response.

The combined therapy cured cancer in 90 per cent of the mice, compared with 6 per cent that received the vaccine alone.

The implications of this finding are potentially staggering.

While the original vaccine unwittingly caused this immune system response naturally, simply boosting CD27 alongside any other targeted vaccine – whether it’s a mRNA, dendritic cell or any other type – could dramatically improve results for a range of cancers.

‘This study shows how important CD27 is in that long-term response and tumour control,’ says Professor Hendrik-Tobias Arkenau, a consultant medical oncologist at Ellipses Pharma and cancer treatment expert. ‘And this theory can apply for many different cancers as well as different types of vaccine.’

Not everyone is so convinced.

‘The problem with many of these therapies is that it’s very hard to get the engineered cells in the right place at the right time,’ says Professor Thomas Powles, director of Barts Cancer Centre. ‘You often end up losing half of them on the way. And then, when the cells do get into the cancer, they’re too exhausted to do anything. We need to sort these problems before they can become a productive therapy.’

Prof Powles adds that he is wary of trials involving fewer than 50 patients or that come from just one hospital. ‘It does look promising,’ he says. ‘But we would need to launch a much larger study to come to a proper conclusion.’

Prof Lyerly agrees – and reveals that his team are preparing to run larger studies. But he hopes that his vaccine project – now nearly 30 years in the works – will have broad implications for all corners of cancer research.

He says: ‘I just want this to open up people’s thoughts into strategies they hadn’t considered. It can’t just be coincidence that all these women are still alive’.

For Lori, the fact she is alive, 25 years on from her diagnosis, is unequivocally due to the vaccine.

‘I know it’s been instrumental in my whole journey because I’ve met so many women with stage four breast cancer who have done other studies, had the exact same treatments I had, or made the same lifestyle changes as me – and none of them are here today,’ she says. ‘It’s not that they did anything wrong, they just didn’t have access to this vaccine.’

NHS patients already getting the high-tech life-saving injections

Some patients have already received pioneering cancer vaccines on the NHS.

The first vaccine for melanoma skin cancer was tested on Health Service patients in spring of 2024.

The jab is personalised to each patient’s tumour – using the same technology that created the Covid-19 vaccines – to instruct the body to make proteins that attack the cancer. Early results suggest that the therapy can drastically improve the survival chances of patients with the disease – the deadliest form of skin cancer.

Steve Young, 52, from Stevenage in Hertfordshire, was one of the first to receive the jab. He describes it as his ‘best chance of stopping the cancer in its tracks’.

Mr Young, pictured left, was diagnosed with melanoma after a lump on his head – which he thinks he may have had for around a decade – turned out to be cancerous.

More than 60 other people also received the high-tech jab at hospitals in London, Manchester, Edinburgh and Leeds.

Experts say that many cancer vaccine developers are aiming to get their treatments approved by 2030.