The ancient enmity between China and Japan has erupted into one of the most dangerous faceoffs in the Asia-Pacific in decades, with Tokyo openly threatening Beijing with military action if it invades Taiwan.

It is believed that the Chinese president, Xi Jinping, has ordered his forces to be ready to seize the island by 2027 and is now warning Tokyo would ‘bear all consequences’ if it dares to get in the way.

Officials from the two sides have since traded barbs, with one from China warning of decapitating ‘dirty necks’, seen as a direct threat to Japan’s prime minister, Sanae Takaichi.

The war of words suddenly moved much closer to the brink this week when Japan scrambled fighter jets after spotting what it said was a Chinese military drone near Yonaguni, its southernmost island, just a short distance from Taiwan’s east coast.

At the same time, a formation of Chinese coast guard vessels sailed for hours through waters around the Senkaku Islands, a chain controlled by Japan but claimed by China, prompting furious protests from Tokyo.

Analysts say the timing is no accident – the incursions came days after Japan’s new leader, hardline conservative Takaichi, told parliament that a Chinese attack on Taiwan could amount to a ‘survival-threatening situation’ for Japan and might trigger a military response.

The ‘survival-threatening’ line is enshrined in Japan’s security law, and it means an attack on its allies is seen as a direct threat against the country.

In response, China’s defence minister, Jiang Bin, issued a stark warning, saying: ‘ Should the Japanese side fail to draw lessons from history and dare to take a risk, or even use force to interfere in the Taiwan question, it will only suffer a crushing defeat against the steel-willed People’s Liberation Army and pay a heavy price.’

With all the violent rhetoric, reports indicate that Tokyo is now considering building its own nuclear arsenal, a concept that has been considered taboo for decades.

The row has quickly spiralled – Beijing has discouraged travel to Japan, while Tokyo has advised its own citizens in China to avoid crowded public places and stay alert.

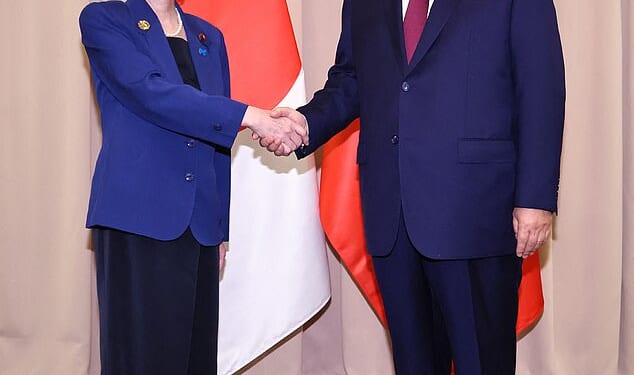

Japan’s new prime minister Sanae Takiachi seen shaking hands with China’s Xi Jinping – weeks after this photograph was taken, the two find themselves embroiled in a bitter war of words

Chinese soldiers marching at a military parade in September. Senior military officials have allegedly been told to prepare for an invasion of Taiwan by 2027

A Japan Ground Self Defence Force battle tank taking part in a military exercise in June. The country has warned that an invasion of Taiwan would result in a military confrontation

China has even put releases of Japanese films on hold, according to officials in Tokyo, a symbolic slap in a relationship already strained by history and territorial disputes.

The fraught relationship between China and Japan is rooted in a history that still shapes politics on both sides.

In the 1930s and 1940s, Japan occupied large parts of China, and the memory of atrocities such as the Nanjing massacre, where hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed, remains central to China’s national story.

Beijing regularly accuses Tokyo of downplaying those wartime abuses. Japan carries its own fears – it sees a rising China determined to reclaim regional dominance and push American forces out of East Asia.

Japan’s warning that it could fight if China invades Taiwan marks a sharp break with decades of strategic ambiguity.

Taipei lies roughly 68 miles from Yonaguni and sits astride sea lanes that carry much of Japan’s trade and energy.

Tokyo’s new security strategy, adopted in 2022, explicitly calls Taiwan’s stability ‘indispensable’ to Japan’s own security and sets out plans to acquire ‘counterstrike’ capabilities, including missiles that can hit enemy bases.

Analysts read that as code for helping the United States repel a Chinese assault on Taiwan.

On the other side of the strait, US and allied intelligence services say President Xi Jinping has instructed the People’s Liberation Army to be ready by 2027 to invade Taiwan.

China’s claim to Taiwan goes back to the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, when the defeated Nationalist government fled to the island and set up a separate state.

The Communist Party has never accepted this split – for Xi Jinping, bringing the island under Beijing’s control is tied to the idea of national rejuvenation and restoring China’s full territorial unity.

Losing Taiwan, in Beijing’s view, would mean accepting permanent division and foreign interference on its doorstep, a humiliation Chinese leaders say they will never tolerate.

Taiwan capital Tapei’s skyline, seen in August 2025. China’s threats that it could invade the island by 2027 has triggered a furious reaction by Takiachi

Officials stress that readiness to invade does not mean will, but the 2027 date has become a focal point for war planning in Washington, Tokyo and Taipei.

A series of reports this year detail Chinese efforts to build amphibious ships and militarised civilian ferries capable of moving large forces across the Taiwan Strait, along with missile and air power designed to keep US and Japanese forces at bay.

For Tokyo, that ‘danger year’ is fast approaching – in March, Japan unveiled its first formal plan to evacuate more than 100,000 civilians from remote islands near Taiwan if war breaks out.

Residents of Yonaguni, Ishigaki and Miyako would be hustled onto ferries and aircraft and taken to safer prefectures within days.

Japan is also building an underground bunker on Yonaguni and deploying more missile units across its southwest islands, turning fishing and tourist communities into the front line of a possible superpower showdown.

Professor Allen Carlson, an expert on Chinese foreign policy at Cornell University, told Daily Mail that the prospect of war ‘is more present than has been the case in quite some time’.

He said: ‘A Taiwanese declaration of independence would be considered intolerable to China, and would likely lead to military action. Any action that Beijing considers to undermine its claim to Taiwan is viewed as a threat and could lead to Chinese retaliatory measures.’

Mr Carlson believes that although there is no immediate indication that China is moving to invade Taiwan, ‘it is looking to actively pressure Japan to back down from the position it appeared to take last week, which involved a strengthening of its security commitment to Taiwan.’

He added: ‘The island is central to Beijing’s long-term strategy. Domestically, bringing Taiwan under the control of the People’s Republic of China is central to the completion of the country’s project of national unification.

‘Internationally, as long as Taiwan remains outside of Beijing’s control, it places a limit on China’s ability to emerge as a global naval power.’

Nonetheless, the sense of looming peril is feeding into a dramatic military build-up – Japan has about 247,150 active military personnel and spends roughly $57 billion a year on defence.

Its army field around 1,443 warplanes and 521 tanks, and operates about 159 warships. Tokyo currently has no fully fledged aircraft carriers of its own, though it has converted two helicopter carriers to operate F-35 B jets.

Members of the Japan Self Defence Forces marching in formation in November 2024. The country has 247,150 active military personnel

Japan has zero nuclear warheads, but it does run a sophisticated, layered missile defence network built around Aegis destroyers and Patriot batteries.

China towers over those figures. Its armed forces count roughly two million active personnel and an official defence budget of about $266.8 billion.

It has around 3,309 warplanes, roughly 6,800 tanks and a fleet of about 754 warships, including three aircraft carriers.

Western estimates say China now has about 600 nuclear warheads and some 400 intercontinental ballistic missiles, alongside a growing arsenal of land, sea, and air-launched cruise missiles and anti-missile systems such as the HQ 19 and HQ 29.

Mr Carlson assessed: In terms of economic conflict, China is in a stronger position, especially vis-à-vis its ability to impose controls over the export of rare earth metals to Japan.

He continued: ‘In the immediate theatre, Japan has some advantages, but overall China’s naval capabilities far exceed those of Japan. The question is what domestic reaction either side would face should a conflict result in casualties.

‘Arguably, such a situation might so enflame nationalist sensibilities in China that it could have a destabilising impact on domestic politics.’

Although Japan spends far less on its military, it boasts 1443 warplanes and 521 tanks, and operates about 159 warships. It has also converted two helicopter carriers to operate F-35 B jets, pictured

China’s army dwarfs Japan’s – in September, the country showed off its huge arsenal in a military parade, including the intercontinental strategic nuclear missiles, DongFeng-5C

The disparity in raw numbers heavily favours China, yet geography and alliances matter. Japan lies astride the so-called ‘first island chain’ that blocks Beijing’s outward maritime expansion.

US bases and treaty commitments on Japanese soil make Tokyo a key node in any conflict over Taiwan or the East China Sea. The United States Indo‑Pacific Command regards Japan as indispensable in deterring Chinese aggression.

US forces stationed on Okinawa and mainland Japan, bound to defend the country under a 1960 security treaty, would be central to any fight over Taiwan or the East China Sea.

Successive US presidents, from Barack Obama to Joe Biden, have publicly confirmed that this treaty covers the Senkaku Islands as well as Japan’s home islands, meaning a clash over the rocks could legally trigger American intervention.

That is what makes the coast guard drama so alarming in Western capitals.

Chinese vessels, some armed, have been pushing into the waters around the Senkaku Islands ever more frequently, setting records for the number of days they patrol close to the islands.

This week’s formation, which spent several hours inside the 12 nautical mile zone claimed by Japan, was described by Beijing as a ‘rights enforcement’ mission.

Tokyo called it an unacceptable violation of sovereignty and said it had shadowed the ships and ordered them to leave.

A China Coast Guard vessel seen near one of Japan’s off Uotsuri Island, part of the Senkaku Islands

The disputed Senkaku Islands continues to be one of the biggest bone of contention between Japan and China

The incident followed a long pattern – Chinese coast guard intrusions around the islands have risen sharply in recent years, often lasting days and sometimes involving ships that appear to be armed.

The pattern is designed, analysts say, to normalise a constant Chinese presence around territory that Japan administers, gradually undermining Tokyo’s effective control and testing how far Washington is willing to go in defence of its ally.

Mr Carlson believes the wrangling over the islands is one of the main catalysts that could trigger a conflict between the two nations. He said: ‘The last juncture at which a clash appeared possible was in 2012 when the two sides nearly came to blows over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands.

‘During that crisis, nationalist protests in China against Japan raged, but both sides ultimately stepped back from the brink. This time, while the territorial dispute did not ignite the current spat, it has become entangled with it as Beijing, in its efforts to place pressure on Tokyo, has expanded its activities in and around the islands.

‘The most likely trigger for conflict would then be an inadvertent engagement between Chinese and Japanese vessels, which could easily spiral into a more direct confrontation should either side suffer casualties.’

At roughly the same time as the Senkaku patrol, Japan’s Air Self-Defence Force detected a suspected Chinese drone near Yonaguni.

Fighter jets were scrambled to monitor the craft, which appeared to be operating near sensitive airspace close to Taiwan.

The scramble was officially justified as a routine response, but it demonstrated how quickly a drone malfunction or misreading of intentions could spark a wider confrontation.

Mr Carlson believes this is all part of China’s plan to apply pressure on Japan to shift from its rhetoric over Taiwan. He said: ‘ [China] is trying to pressure Japan to retract the Prime Minister’s recent statement.

‘I think this is part of a coordinated effort on the part of the Chinese to achieve this goal, and sort of that to make clear to Japan the resolve it has to oppose any measures that appear to strengthen Taiwan’s position in relation to China.’

The political atmosphere has become more combustible than ever before in recent times. After Takaichi’s remarks in parliament, China’s consul general in Osaka posted a message on X that many in Japan read as a personal threat to the prime minister, saying in effect that her ‘dirty head’ should be cut off.

The post was later deleted, but not before it triggered a formal protest from Tokyo, which branded the language outrageous. Beijing has distanced itself from the wording, saying it was a personal comment, but has not softened its criticism of Japan’s stance on Taiwan.

Public opinion in Japan is deeply split over how far to go. A Kyodo news agency poll released found the country almost evenly divided on whether Japan should consider military action in support of Taiwan, if China attacks.

Support for Takaichi’s tougher line exists, but so do fears that her rhetoric could drag the country into a catastrophic war.

Behind that anxiety lies an even more sensitive debate – nuclear weapons. Since the late 1960s, Japan has adhered to three non-nuclear principles – not to possess, produce or allow nuclear weapons on its territory.

The bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the testimony of hibakusha survivors have given those principles near-sacred status in post-war Japanese politics.

The horrific bombings of Hiroshima, pictured, and Nagasaki contributed to Japan’s decision not to develop nuclear weapons

But the world around Japan has dramatically changed since then.

China, Russia and North Korea all have nuclear arsenals and are modernising them. Washington’s security guarantees have looked less dependable in recent years, especially under Donald Trump.

A Reuters investigation found a growing number of senior ruling party lawmakers are willing to talk about once-unthinkable options, such as nuclear sharing arrangements that would see US nuclear weapons based in Japan.

There are even considerations of Japan eventually developing its own nuclear deterrent if the American umbrella frays.

Takaichi herself has long criticised the principle that bans the introduction of nuclear weapons into Japan.

This week, she refused to clearly state whether the three principles would remain untouched in an upcoming revision of the country’s security strategy.

Separate reports say her administration is considering a formal review of the doctrine, although officials insist there is no plan to possess or produce nuclear arms.

Critics say even debating such moves risks shredding Japan’s moral authority on disarmament and sparking a regional arms race, potentially pushing South Korea and others to develop their own bombs.

Supporters argue that when encircled by nuclear neighbours and facing a possible war over Taiwan, Japan can no longer afford to abide by the principle.

Chinese soldiers conduct aerial landing behind enemy lines during a live fire exercise in November 2025

According to Mr Carlson, Japan’s current political landscape could be what dictates its future nuclear stance.

He explained: ‘Should Japan shift its position on nuclear weapons, the driver for such a change would go well beyond this current spat, and stem more from underlying changes in Japanese domestic politics alongside shifting strategic assessments of the threat posed by China and the reliability of the US commitment to Japan.’

For now, the nuclear taboo still holds, but it is far weaker than it was a decade ago.

If war did break out, the lineup of friends and foes is already taking shape.

On one side would stand Japan, backed by the United States and, on some level, Australia. The Oceanic nation has deepened defence ties with both Washington and Tokyo and participates in the Quad grouping aimed at managing China’s rise.

Some analysts believe the Philippines, which has granted US forces expanded access to its bases and is itself on the frontline of maritime disputes with China, is likely to offer support, at least with logistics and staging.

Some European NATO states could send ships, impose sanctions and provide intelligence, even if they stay out of the actual fighting.

China would count on its increasingly close partnership with Russia, formalised in a ‘no limits’ declaration and built up through repeated joint bomber patrols and naval exercises over the Sea of Japan and nearby waters.

If war broke out, China can count on the support of Russia’s president Vladimir Putin. The two countries have forged a close partnership

Moscow has already welcomed political backing from Beijing over Ukraine and has every interest in seeing Washington tied down in Asia.

North Korea, which has supplied Russia with millions of artillery shells, ballistic missiles and even thousands of troops for the war in Ukraine, would almost certainly cheer China on and could threaten US bases in Japan.

Officials in Western capitals worry about an even darker scenario. In it, China moves on Taiwan while Russia tests NATO in Europe, with North Korea acting as a spoiler in Northeast Asia.

A clash over a drone or a coast guard ship near the Senkaku Islands could suddenly be entangled with battles in Ukraine or the Baltic, drawing in multiple nuclear-armed states at once.

It is that chain reaction that prompts some strategists to warn of a realistic route to World War III starting in the waters between China and Japan.

But Mr Carlson believes the most important actor in any alliance would be South Korea. He explained: ‘Would Seoul stand side by side with Japan and the United States, or would it equivocate given its proximity to China – and the potential implications of a military conflict for the South’s relationship with North Korea?

‘The key actors would be Japan, South Korea, and the US, not to mention Taiwan itself.’

Yet for all the apocalyptic talk, there are still reasons to believe both Beijing and Tokyo want to stop short of open war.

China’s economy is slowing, according to figures, and foreign investment plummeted to a 30-year low in 2024. In recent days, its military modernisation showed signs that it had hit some turbulence, including high-profile purges and concerns over corruption in its missile forces.

On the other hand, Japan’s society is rapidly ageing, its birth rate is falling, and its recruitment pool is shrinking, making a long war hard to sustain.

Despite their history and tension, the two countries remain major trading partners, and any conflict that closes the Taiwan Strait or East China Sea would shatter supply chains, sink markets and plunge the global economy into crisis.

In that vein, Mr Carlson agrees that a war between the two would have severe consequences for the rest of the world.

‘It would have an incredibly destabilising impact, particularly as it would all but demand US involvement, which would mean the world’s two largest powers would be stepping towards military engagement’, he said.

‘It strikes me that neither Xi nor Trump has any interest in going down such a road, and, therefore, I suspect that both leaders will be looking for a way to de-escalate the current spat.’

Donald Trump and Sanae Takiachi shake hands last month. A conflict between Japan and China will force the US to step in to defend Japan, according to experts

However, that does not remove the danger – it simply means all sides are relying on deterrence and brinkmanship instead.

Japan is betting that clearer red lines, stronger alliances and more capable armed forces will dissuade China from gambling on a quick strike against Taiwan or the Senkaku Islands.

China is hoping that steady pressure, constant patrols and fierce rhetoric will gradually wear down Japanese resistance and convince Washington that the risks of defending its ally are too high.

In between sit ordinary residents of islands like Yonaguni and Ishigaki, who are now uncertain about whether or when war will break out.

For now, the crisis is still a contest of words, patrols and military exercises.

Together, these old wounds and territorial standoffs have kept tensions simmering for generations.

With Chinese drones probing Japanese airspace, coast guard ships loitering around disputed rocks and leaders trading threats of ‘crushing’ defeat and decapitation, the hated Far East rivals are clearly on a collision course.

Whether the world witnesses another uneasy standoff or watches the spark that sets off a global conflict may depend on how carefully Beijing and Tokyo navigate the next few years, as the 2027 clock ticks louder over Taiwan.