Leoš Janáček’s 1925 opera seems a thoroughly baffling creation — weirdly discursive musically and dramatically, full of that endearing Czech quirkiness, many-layered, with a fascinating if rather unlikeable heroine and, right at the end, a radiant burst of musical and psychological redemption (or something like that). Its subject, a woman whose curse is that her alchemist father used her as a guinea-pig for a life elixir 400-odd years ago, in a story written by the fantastical H.G. Wells-alike Karel Čapek, frolics about amid the humour and horror of immortality, and the opera broadens it out into, inter alia, a parable about humans trying to deal with an irrational world, plus various versions of our thirst for love.

And it takes place against the background of an interminable inheritance lawsuit, the Jarndyce of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, whose dusty absurdities are jovially exploited as our heroine Emilia Marty chattily drops bits of info like where she saw Joseph “Pepi” Prus (d. 1827) hide his will, driving all those lawyers mad.

A rich brew, indeed, and I only hope you saw it at Welsh National or Scottish Opera, where Olivia Fuchs’s excellent staging did it justice, or at Glyndebourne in Nikolaus Lehnhoff’s production, because you’re only going to get about twenty per cent of the opera’s potential and marvels in Covent Garden’s first (rather surprisingly) attempt.

There’s certainly a lot going on in Katie Mitchell’s staging, updated to present-day Prague, though it doesn’t include a huge amount of the stuff mentioned above, nor the sly humour of the original, inevitably nowhere to be found here. I don’t particularly want to go on about this director, who has done some worthwhile and occasionally brilliant (as well as truly ghastly) things in her 30-year opera career, but she evidently intended to make herself the story, droning on in a recent interview about quitting opera because of (did you guess?) misogyny. Actually she had first said this two years ago at a Goethe Institute lecture, but I guess not enough people had heard that; anyway somehow she found it in herself to swallow her pride — I mean honour her high-paying contract — one final time… In her chosen role as champion of women in an art form she (I think simplistically) finds devoted to their exploitation and destruction, she has taken a massively interesting piece and made it boring, narrow, mean. Neither has she done the heroine many favours.

It’s a bit of a pity, since there are some not entirely worthless (though not strictly relevant or necessary) ideas here, including the amusing one that Emilia’s breathless admirer Krista is actually a con-artist plotting with her boyfriend Janek to roll Emilia over and scarper to Berlin with the dosh. To explain this, the first scene is given over to a (whoop whoop! misogyny alert!) romantic Scissr date between the pair in Emilia’s hotel room, though frankly the ladies seem a bit stumped as to how they should proceed with their business, and call it a day just when things are getting interesting. Most of the time Krista is on her phone sending messages to the presumably broad-minded Janek; these are interminably unscrolled above the stage — and above the surtitles of the actual opera, which turns out to be rather pointlessly going on in the next room of Vicki Mortimer’s split-screen stage, where the lawyers are doing the exposition of the plot. Nobody could possibly assimilate all this: so we rather unwillingly read the messages, letting music and drama do their thing, ignored, off to the side. Sure, the legal stuff in itself is pretty silly, but the absurdism of its presentation is arguably kind of important for the atmosphere of the opera.

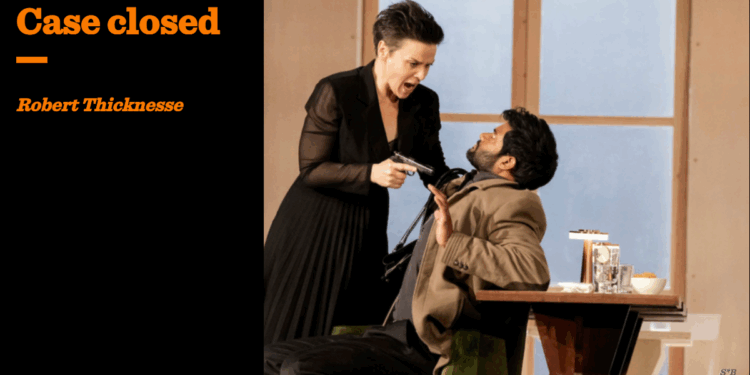

And things never really settle down. You could say the same about Janáček’s music, for sure, at its bittiest and most staccato in this opera, though there are frequent irruptions of significant lyricism or spiky heraldic nobility, harking back to the freaky court of Rudolf II where the story originates. Certainly all the men in this opera are, for the sake of argument, petty and peevish, but it’s surely unwise (and certainly tiresome) to treat them with such contempt as here: Emilia — even in the outstanding performance of Ausrine Stundyte — can hardly carry the opera entirely on her own, particularly since she is such a glacial and unsympathetic character. Heather Engebretson as her unexpected new squeeze works hard, but it’s a minor role, and can hardly be expected to fill the vacuum. Of all the men, Alan Oke with his cameo as the old crock who was Emilia’s lover in one of her previous lives is the only one who is allowed any individuality, and has fun with it.

Nobody minds (well, actually plenty do) directors intelligently mucking about with these pieces that we see all the time, though Makropulos is perhaps a bit too obscure and intricate to respond all that well to massive intervention; Emilia’s decision to go over the old Sapphic fence is perfectly understandable after hundreds of years of doing the regular stuff — though the thing is really that she’s sick to the bottom of her soul of everything, and I doubt these exciting hookups are going to radically change that. One wonders too why she passes on the cursed formula of the elixir to Krista at the end, since this would seem rather a dreadful thing to do. But like most of the other issues actually raised by those misguided male fools Janáček and Čapek, we never find out.

What remains is the ritual of performance, neatly enough done on stage if you like this kind of “realistic” bustle and detail. Jakob Hrůša conducts a performance that is bracing, marvellous, exhilarating, but so divorced from the stage that it feels merely parenthetical for the most part, between its grand, busy intro and ecstatic playout.

Naturally, any adverse reaction to this show is being characterised as chauvinist and reactionary, whereas you might think the true chauvinism lies in hollowing out a rich and wonderful creation simply to harp on about men being frightful and women amazing, which of course we all accept anyway. But after all, nobody has to go.