HAVING walked around the world for 27 years, facing everything from polar bears to gun-wielding thieves, Karl Bushby is finally heading home.

The nomad has hacked through deadly jungles, survived -51°C winds, and slept on ice in the middle of the ocean during his incredible adventure.

The former Brit paratrooper, who hasn’t been in the UK since the 1990s, is due at his mum’s house in Hull in a matter of months.

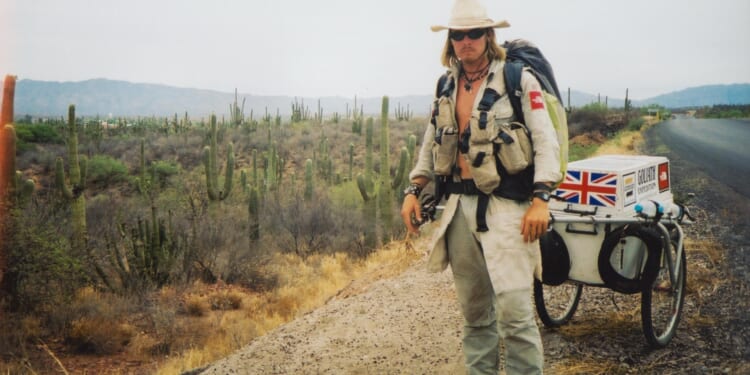

The epic feat, dubbed the ‘Goliath Expedition’, will see Karl become the first person to walk around the world “with unbroken footsteps”.

He expected the mission to take him eight years, but almost 27 years later, he’s still walking.

The inspiration for the mammoth adventure came from his time in the forces.

Karl joined the army at 16, and like other paratroopers, “learned to do everything on foot”, a lesson that would shape a 27-year global trek.

“The army was all about distance and stamina and ability to be independent” he said.

“And so within that environment, the idea kind of really shaped itself with the question, well, how far could you go?”

Karl defined the mission with two simple rules. Firstly, that he could not use any form of transport to advance.

And secondly, that he could not go home until he arrived on foot.

“It’s incredible how complicated the world can get when those two rules meet reality,” he said.

After eleven years of service in the military, aged 28, he set off from Punta Arenas, a small city near the tip of Chile’s southernmost Patagonia region.

Back when he began in 1998, Karl had no sponsors and the trip was about “pure survival.”

“There wasn’t any funding” he said. “It was just find what you can eat and keep moving. But you could find enough food on the side of the road.”

Walking up to 30 kilometres a day, Karl was living as cheaply as possible, sleeping in his tent and foraging for his food.

“In Latin America, you can get away with a pocket full of rice, a pair of shorts and a t-shirt,” he remembered.

He camped on “just about any surface you can imagine” — from hammocks in the jungle to pans of ice in the middle of the ocean.

Throughout the hike, Karl encountered endless challenges that threatened to bring his mission to an abrupt end.

In Peru, he suffered from a serious stomach infection, and multiple secondary infections which caused him to double over in pain every ten feet he walked.

“I mean, you’re living on trash by the roadside, so these things happen,” he said.

Karl was in an alarming state and was hospitalized for a course of antibiotic treatment.

“They almost knocked me unconscious for a couple of days.”

Held at Gunpoint in the Jungle

Once recovered, he continued north, traversing the entirety of the Americas, including the notorious Darién Gap, the only land bridge between South and Central America.

Connecting Colombia and Panama, it is known to be one of the most inhospitable regions in the world thanks to its dense jungle and the criminal activity that takes place within it.

Karl undertook this “absolutely exhausting” section of the journey in 2000.

During the crossing, he got held at gunpoint multiple times, both by the Colombians and the Panamanians.

“You’re creeping or sneaking through the front line of the fighting between what was then the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, the Colombian army, and guerilla groups.

“That was one of the most difficult, scary things I’ve done. It was incredibly frightening”

The more kilometres Karl got behind him, the more his support grew.

He set up a website to receive donations and managed to secure a book deal to fund the technical equipment and specialist logistics required for the extreme winters coming in the next leg, which would take him through North America and deep into the Arctic.

‘Battling -98°C Arctic Winds‘

From Alaska, he began the Bering Strait crossing into Russia, a famously hostile polar landscape that saw him battle “lethal temperatures” of -51 degrees Celsius with windchill factors making it feel like -98.

Out there, survival meant eating whatever the Arctic provided, whale, seal blubber, and even polar bear meat.

A French adventurer, Dimitri Kieffer, who joined Karl for this treacherous section of the trip, took his gloves off “for a second” and lost the tips of three fingers.

In 2006, Karl and Dimitri became the first people to cross the strait on foot, a trek that involved walking on ice for a brutal 14 days, navigating shifting ice floes, dangerous open water, and the possibility of being crushed between icebergs.

Karl still grimaces at the memory: “Oh my God. It was absolutely wicked” he recalled.

“Those were really very uncomfortable days. When you’re right out there in the Arctic, the vastness is just staggering.

“There’s a horrifying beauty to it. Horrible place. If I never saw snow again, I would live happy.”

It was out on these frozen ice fields of North East Russia that Karl faced his next life-threatening encounter.

Polar Bear standoff

“We were trapped between piles of sea ice and a cliff. And there was a stretch we were walking along between the two.

“A polar bear was right there in the middle of that stretch, digging something up.

“We inched our way towards it. And at one point, to get a better look at us, it stood on its hind legs and just rose into the sky like a skyscraper.

“It was a terrifying moment because there was nothing we could do. If it decided it wanted us, we were dead.

“We had nothing with us at that point because we weren’t allowed to carry firearms while we were in Russia.

“So we had literally nothing. That got pretty tense.”

Despite the challenges, Karl’s motivation to complete the mission has never wavered.

“People stick to some pretty tough jobs and pretty tough lifestyles. But they get on with it and knuckle down.

“And that’s basically just the same with me. That’s all it is. It’s just a different kind of job.

“It’s not like I’m going sightseeing here. Funding is very limited. I struggle to get to each waypoint.

“From someone in the nine to five’s perspective, it looks like it’s a life of willy-nilly wandering down roads, but it’s not. It’s pretty intense work.”

Karl made his way across Russia and Central Asia, all while dragging his custom-built trailer that he tied around his waist, with food and water weight alone adding 200 pounds (over 90kg).

“I live pretty comfortable” he said “by my standards maybe”

“But I put up with a lot of weight, which is difficult to move between places.

“Especially when you’re going up hills and mountains. That can absolutely be a workout.

“I carry everything with me, from -40 degrees to the Indian desert, I’m always covered.”

’30 Days of Misery‘

He continued his progress across central Asia, until he reached the shores of the Caspian Sea in Kazakhstan.

Due to visa restrictions and political tension, Karl found himself “trapped” on the wrong side of the world’s largest inland body of water, unable to travel through Russia to the north, nor through Iran to the south.

True to his resilient spirit and relentless drive, he “had no choice” but to swim the 300 kilometres across the sea, bypassing both Russia and Iran, and arriving in Baku, Azerbaijan’s capital.

Karl had little swimming experience and said he had “never imagined” crossing an open sea when he set out on his epic challenge.

“All we had to do was push out about 10km a day swimming.”

“I do not like swimming — I hated it, it was misery. But at least we could do it.”

After the Azerbaijani government stepped in to assist, Karl was accompanied by coastguard members and two national team swimmers.

The gruelling swim took 31 days to complete and the expedition continued, with Karl’s sight set firmly on reaching Europe.

Finally, the home straight

With a mind-blowing 48,000 kilometres behind him, having navigated countless dangerous situations, a global financial crash and the Covid-19 pandemic, Karl is finally on “the home straight”.

Now in Romania, he has less than 2,000 kilometres to go and will be back on British soil in under a year.

His thoughts have turned to his long-awaited homecoming: “It’s pretty scary, having spent so much time on the road” he said. “It’s alarming when it gets real. Now actually, we’re going to make it home.”

But the challenge isn’t over yet. He sees the trek as having three obvious “gaps”, that were identified from the beginning, stages that would require extra grit, resilience and imagination to complete.

He’s already faced the ruthless Darién Gap, a lawless jungle straddling South and Central America, and braved the bone-chilling Bering Strait, where Arctic waters turn to ice.

But his third “gap” and potentially his toughest test is still ahead: the infamous English Channel.

He’s hoping to persuade the authorities to let him walk through the channel tunnel, rather than having to get back in the water.

Asked if he’s excited about the prospect of returning to the UK, Karl says “the general feeling is no,” but he’s keen to reconnect with family, who he hasn’t seen in over a decade.

Karl also plans to throw himself into non-profit work and “get busy quickly with another mission.”

Looking back on a lifetime on the road, Karl says the expedition hasn’t just tested his body, it’s shaped his view of humanity.

From the truckers in the far north of Russia, who would pass Karl regularly on the road and leave tins of food in the snow for him, to the family in Peru who took him in and nursed him back to health, he says the kindness of strangers has carried him through.

“The world is your support network,” he said. “One of my biggest lessons is how overwhelmingly friendly the world is.”

“For someone who watches the 24 hour news cycle, the world is imploding. It’s the most dangerous, horrible place that could ever be.

“But that’s not the case. The vast majority of everyone I’ve ever met in this world has been amazing.

“I get to stand in front of kids in classrooms from time to time. It’s a pleasure to be able to give them the Karl report on the state of the world.

“It’s a lot better than it would appear.”