The U.S. immigration court system has shape-shifted under the Trump administration, through policy changes, widespread courthouse arrests, and the firing of immigration judges.

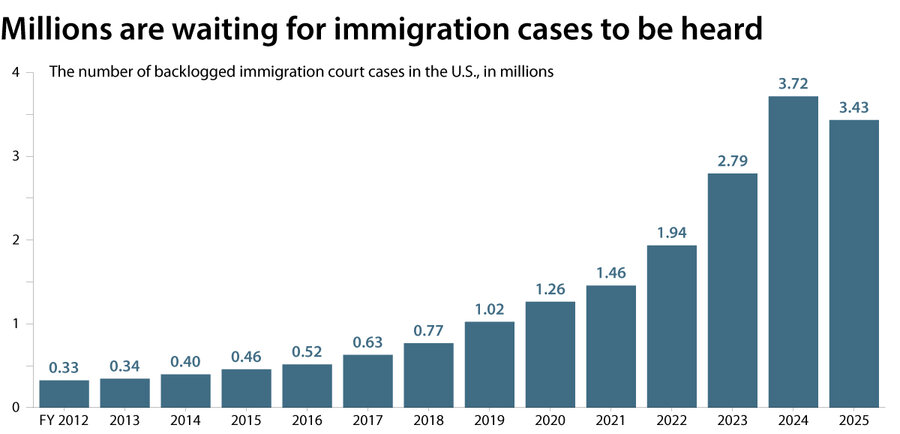

Immigration courts have always operated with unique features. The system is part of the executive branch – not the judicial branch – and housed under the Justice Department. They are run by judges who settle questions like whether to order an immigrant deported or grant them asylum. Over the past decade, the courts’ backlog of cases grew more than eightfold, hitting a high of 3.7 million at the end of fiscal year 2024, according to an analysis by TRAC, a data-gathering organization.

The U.S. immigration court system is “in crisis” because of its high caseload, as well as a need for increased funding and a greater focus on high-priority cases, says a report published on Thursday by the Migration Policy Institute.

Why We Wrote This

Immigration courts play a significant role in deciding who can stay in the United States. The Trump administration is transforming this system to speed up removal proceedings and detain more people in the process.

Typically inconspicuous, immigration courts have drawn public attention this year. In March, the government admitted that the deportation of Kilmar Abrego Garcia to El Salvador violated an immigration judge’s earlier order banning his removal to that country. Federal law enforcement this spring began widespread detentions of people present for immigration court hearings, and arrested New York City Comptroller Brad Lander at an immigration court in June. Faith leaders have organized to accompany immigrants to their hearings for moral support.

The Trump administration cites efficiency to justify some of its recent changes – including assigning military lawyers to serve as immigration judges – and touts a substantial reduction in pending cases. Critics, meanwhile, say the moves trample the due process rights of immigrants, such as having their case heard. As the administration seeks to expand its deportation campaign, immigration courts are likely to stay in the limelight.

How does immigration court work?

There are 73 immigration courts nationwide, with hearings run by about 600 immigration judges appointed by the Justice Department. The government recently onboarded additional judges, some serving temporary terms.

Immigration court is a system of administrative law. Some observers call its proceedings “civil” – as in noncriminal. But these courts don’t follow federal civil-procedure rules like district courts do.

“Immigration court isn’t really a court,” at least not as outlined in Article III of the Constitution, says Alison Peck, author of “The Accidental History of the U.S. Immigration Courts.” “It’s not part of the independent judicial branch of government.”

Immigration judges decide who gets deported and who gets relief, such as asylum – if the applicant seeks protection as a defense against deportation. These judges can order immigrants deported for a variety of reasons, such as entering the country illegally, overstaying a visa, or committing a crime unrelated to immigration. Immigrants don’t need convictions from state or federal courts before they’re ordered removed in this administrative setting.

A notice to appear starts the process in immigration court, known as removal proceedings. Noncitizens before this court – called respondents – are entitled to lawyers. But because these respondents aren’t criminal defendants, they lack the right to legal counsel at the expense of the government. Children often appear in immigration court without representation.

Immigration judges don’t always have the final say. Within 30 days, respondents whose cases were denied may appeal to the Board of Immigration Appeals. Subsequently, noncitizens may petition a federal circuit court of appeals for review, then the Supreme Court.

How backlogged is the court system?

As of August, there were 3.4 million cases pending in immigration courts. The backlog often results in yearslong waits for hearings, which is a point of frustration for pro-enforcement and pro-immigrant advocates alike.

Last fiscal year, the number of pending cases shrunk by more than 700,000 cases, according to the Executive Office for Immigration Review, which oversees immigration courts. That office says there were more than 4.18 million pending cases at one point, a higher figure than TRAC has reported. Observers attribute the drop to a variety of factors, including fewer new cases as illegal entries plummet and more respondents placed in detention, where cases might move faster.

Experts of the court say delays in adjudication can mean immigrants build up more ties to the U.S. while they wait, such as landing jobs and forming families. Critics say unauthorized immigrants who want to stay are incentivized to prolong or evade court proceedings. At the same time, the backlog delays people with legitimate asylum claims from receiving a decision on their request for protection.

How have immigration courts changed under Trump?

The administration has sought to speed up removal proceedings, detain more people in the process, and pursue more fast-track deportations that can bypass the courts.

“There’s been a real focus on things being faster and more efficient – and a very, very black-and-white application of the law,” says a member of the National Association of Immigration Judges, who asked not to be named due to retaliation fears and restrictive orders on speaking with the media.

Policy changes set by the administration have rolled back “previous safeguards” that were “almost to the level of law, because those policies were so ingrained in the immigration system,” says the immigration judge, who is not speaking on behalf of the Executive Office for Immigration Review or the broader Justice Department overseeing immigration courts.

A shift toward more detention has had the greatest impact, says the judge. A decision this year from the Board of Immigration Appeals says immigration judges lack the authority to release certain immigrants from detention on bond. Detainees are challenging what they consider unlawful detentions through habeas corpus petitions in federal district court.

In other cases, the Board of Immigration Appeals has empowered immigration judges to reject an asylum application if the form is incomplete, or if the immigrant doesn’t establish eligibility on first impression of their case.

Media reports have also documented mounting arrests of immigrants at immigration courts – with and without dismissal of their cases. The government is often preparing those detained for fast-track deportations called “expedited removal,” which can be carried out without a final order from an immigration judge. Immigration advocates say the possibility of arrest might deter respondents from attending hearings. There’s also a catch-22: Not showing up could result in a deportation order in the immigrant’s absence.

Is the administration scaling back due process rights for immigrants?

That’s one of the biggest debates, including what process is “due” in each case. President Donald Trump, along with top officials, has lamented judicial processes and rulings that have curbed the White House’s deportation push.

The United States has “some of the worst, most dangerous people on Earth,” Mr. Trump told NBC News in May. “I was elected to get them … out of here, and the courts are holding me from doing it.”

Many immigration lawyers disagree with his approach. “We are seeing the erosion of due process,” says Jenine Saleh, a managing attorney at Human Rights First. “It’s procedural suffocation masquerading as efficiency.”

The immigration court system is being “undermined” and is “lacking impartiality,” says Lory Rosenberg, a former appellate immigration judge who now mentors lawyers. For one, she says, the appellate board has adopted the Trump administration’s view that more respondents should be held in custody during immigration proceedings. She also disagrees with the administration’s narrowing of asylum eligibility in cases where a person says they’re fleeing domestic violence.

Other critics of the system, including supporters of the administration, argue that immigration courts contain too much red tape.

“Part of the reason why we have this massive backlog is because there is so much due process built into the system,” says Andrew Arthur, a former immigration judge and resident fellow in law and policy at the Center for Immigration Studies.

In most cases, the Department of Homeland Security has to receive a removal order issued by an immigration judge before it can deport anyone, says Mr. Arthur. But due to legal, logistical, and sometimes diplomatic complications, not everyone ordered removed is deported right away. As of mid-September, there were nearly 790,000 final orders of removal that the government could execute, according to Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

What’s happening with the firing of immigration judges?

At the end of fiscal 2024, there were 735 immigration judges, according to the Justice Department. That number fell to 685 this past summer, the latest federal data available.

Now, the judges’ union says some 600 judges hold hearings. Under this administration, the union says 141 judges have departed because of firings, deferred resignation, or reassignment. The Justice Department on Oct. 24 announced a hiring boost of 36 judges that include several military officers.

The administration is training judge advocates general – military lawyers – to serve at least temporarily as immigration judges. Some concerned Democratic lawmakers say the move appears to violate the Posse Comitatus Act, which generally prohibits use of the military for domestic law enforcement.

At the judges’ union, “We’re grateful for any help we can get” to lower the backlog, says the immigration judge. At the same time, there are readiness concerns, and the union has pushed for the military personnel to receive proper training.

The service members are an appropriate stopgap, but “not a long-term solution,” says Cully Stimson, a former top Navy judge and current senior legal fellow at the Heritage Foundation. The plan “takes away from our duties to the military,” he says, adding that immigration judges need the same procedural tools that other federal judges wield to reduce their caseload.

What reforms for the court have been proposed?

The National Association of Immigration Judges has called for creating an independent court system. So have immigrant advocates, who also push for increased access to counsel. Some Democrat-led states, including California and Colorado, have created legal defense funds for immigrants to help obtain that aid.

Congress could reduce the court backlog by granting legal status to certain unauthorized immigrants, though that’s “unlikely in today’s political climate,” says the Migration Policy Institute report. The think tank advocates prioritizing cases that present national-security or public-safety risks, and allowing immigration officers outside the court to decide more asylum cases.

At the Heritage Foundation, Mr. Stimson has called for expanding immigration judges’ powers with contempt authority and more ways to end cases at early stages. Project 2025, a road map for the presidency developed by the foundation, suggests moving the court to the Department of Homeland Security, treating the judges as national security personnel, and decertifying their union.

Both sides of the aisle have supported increased resources for immigration courts. Congress has secured funding for up to 800 judges.

This story was reported by Caitlin Babcock in Washington and Sarah Matusek in Denver.