Astronomers have picked up a radio signal from a mysterious interstellar visitor speeding through our Solar System.

Using South Africa‘s MeerKAT radio telescope, researchers detected hydroxyl radicals (OH) around the object on October 24.

‘These molecules leave a distinct radio signature that telescopes like MeerKAT can pick up,’ explained Harvard professor Avi Loeb, who has been studying 3I/ATLAS since the summer.

Analysis revealed the OH molecules were moving at roughly 61 miles per second relative to Earth.

And they suggest the surface temperature of the mysterious object is around –45°F.

‘This absorption signal constitutes the first radio detection of 3I/ATLAS,’ Professor Loeb added.

The detection comes just days after 3I/ATLAS passed near the orbital plane of Earth, making it easier to observe.

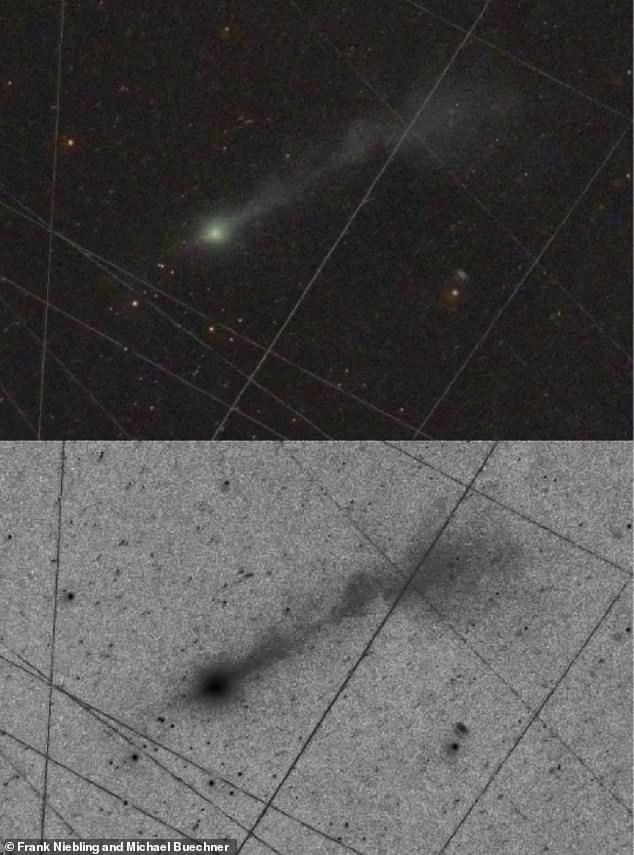

Optical images captured on November 9 reveal that the object is ejecting enormous jets of material stretching nearly 600,000 miles sunward and almost 1.8 million miles in the opposite direction – roughly the diameter of the sun or the moon in the sky.

At its current distance of 203 million miles from Earth, these distances represent the first clear measurements of the vast size of 3I/ATLAS’s activity.

Optical images captured on November 9 (pictured) reveal that 3I/ATLAS is ejecting enormous jets of material both toward and away from the sun

‘Given that the anti–tail jets are only stopped at about 620,000 miles, their ram pressure exceeds that of the solar wind by a factor of a million,’ Loeb noted.

The solar wind flows at roughly 250 miles per second, a thousand times faster than the outflow speed expected from a natural comet.

‘This implies a mass flux of about 2.2 million pounds per second per million–square–mile section of the jet, adding up to a mass loss of 50 billion tons per month,’ Loeb said.

Summing over the full area of the jets, the total ejected mass is comparable to the minimum mass of 3I/ATLAS itself.

‘Assuming a solid density of 0.5 grams per cubic centimetre, the object must be at least three miles across, and if most of its nucleus survived perihelion, it could be six miles or larger,’ Loeb added.

For comparison, the famous interstellar object 1I/’Oumuamua measured only a few hundred feet.

The extreme scale of 3I/ATLAS’s jets raises fundamental questions. If the object were a natural comet, the jets should move much more slowly and require months to reach the observed distances.

Instead, the extraordinary mass, density, and collimation of the outflows suggest something unusual may be happening.

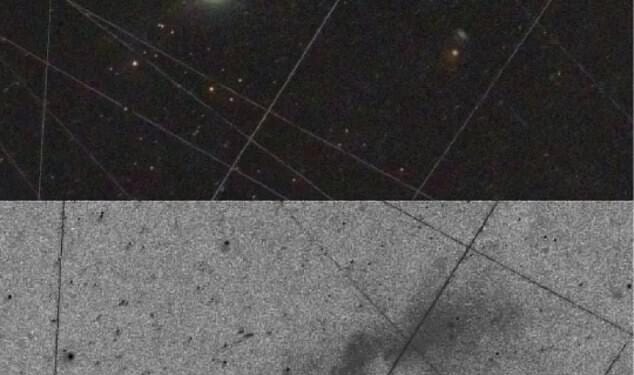

South Africa’s MeerKAT radio telescope (pictured) detected absorption lines from OH molecules, made of oxygen and hydrogen, around the object on October 24

‘The numbers are challenging for a natural comet explanation,’ Loeb said. ‘The required mass loss, the rapid perihelion brightening, and the size all point to anomalies.’

Spectroscopic observations from space telescopes like Hubble and Webb, planned as 3I/ATLAS approaches its closest point to Earth on December 19, will allow astronomers to measure the velocity, composition, and total mass of the jets.

These observations may help determine whether 3I/ATLAS is a conventional icy comet or perhaps powered by technological thrusters, which could produce similar jets with far less mass loss.

Meanwhile, the Juno spacecraft is scheduled to probe the object on March 16, 2026, when it passes 33 million miles from Jupiter, using its dipole antenna to search for low–frequency radio signals. Observatories around the world are also monitoring the object, partly because its trajectory aligns within 9 degrees of the direction of the famous 1977 ‘Wow!’ Signal.

Loeb added: ‘3I/ATLAS is giving us a rare opportunity to study an interstellar object in real time.

‘The combination of radio and optical data shows it is shedding massive amounts of material, moving at incredible speeds, and behaving in ways that challenge our understanding of natural comets.’