The first shot fired in the United States’ nascent war against illegal drug smugglers remains shrouded in mystery.

President Donald Trump announced the strike on Sept. 2 in a social media post. Eleven narcoterrorists belonging to the Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua had been on board, he asserted, saying they had been carrying illegal drugs and were “heading to the United States.”

Two months on, the Trump administration has not provided evidence confirming most of those details. Was the boat and its crew associated with Tren de Aragua? Were there illegal drugs on board? Was it headed for the U.S.? Or had America just destroyed a boat full of innocent civilians?

Why We Wrote This

The Trump administration claims it has legal justification for killing alleged “narcoterrorists.” Here’s why many experts, including conservatives, remain skeptical based on what the administration has shared so far.

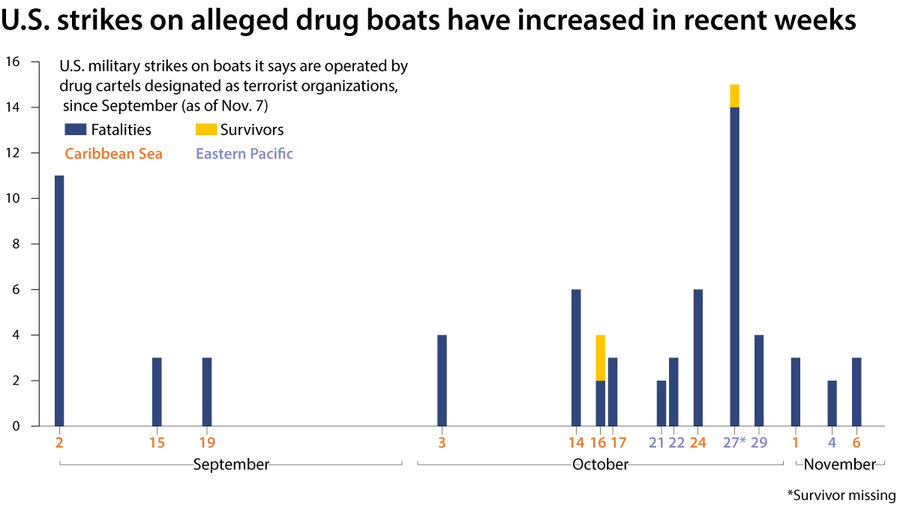

Meanwhile, the strikes have continued – 17 to date, resulting in 70 deaths, according to public reporting.

“All of these decisive strikes have been against designated narcoterrorists, as affirmed by U.S. intelligence, bringing deadly poison to our shores, and the President will continue to use every element of American power to stop drugs from flooding into our country,” said Anna Kelly, a White House spokesperson, in a statement.

The strikes are lawful, according to the administration, because the United States is in an armed conflict with drug-trafficking groups it has labeled as foreign terrorist organizations. Drug overdoses, the administration says, have killed more Americans than Al Qaeda, the terrorist organization responsible for the 9/11 attacks.

No one disputes that illegal drugs being smuggled into the U.S. are harming Americans. But many legal experts – even some who appreciate Mr. Trump taking the drug threat more seriously – believe he is using his war powers in unlawful ways.

“There has been no armed attack. There is no organized armed group [and] there is no armed conflict,” says Rebecca Ingber, a professor at Cardozo Law School and a former legal adviser at the State Department.

“Under international law, we’d call the targeted killing of suspected criminals an extrajudicial killing, and under U.S. domestic statutes it’s murder,” she adds.

Legal rationale for the strikes

The government says its legal authority for the strikes has been explained in a classified opinion from the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel. The strikes are lawful, according to the opinion, because cartels’ drug trafficking is an imminent threat to Americans. The opinion applies to a range of cartels broader than those the Trump administration has publicly listed as terrorist organizations, according to CNN, which first reported the existence of the opinion.

But legal experts say it is a weak justification for what is effectively an air campaign against seemingly defenseless boats that the government is claiming, without evidence, are transporting drugs to the U.S.

“There’s no doubt these narco gangs are engaged in smuggling drugs into the United States. There’s also no question that these illegal narcotics cause tragedies in the United States,” says Geoffrey Corn, director of the Center for Military Law and Policy at Texas Tech University.

But “the existence of an armed conflict is not based on some harmful commodity that’s brought into your country. It’s based on the existence of hostilities, hostilities in a very pragmatic sense,” he adds.

Administration officials have stressed that each strike came after meticulous intelligence-gathering.

“Targeting decisions are deliberate, based on comprehensive assessments and reviewed through established processes,” said a Pentagon official, who was not authorized to speak on the record, in an email.

In remarks to the media last month, Secretary of State Marco Rubio said that the approval for each strike “goes through a very rigorous process.”

“There are hundreds of boats out there every single day, and there are many strikes that we walk away from … because it doesn’t meet the criteria,” he added.

It’s understandable that the government might want to keep some details of its intelligence gathering confidential, experts say, but previous administrations have been more forthcoming about U.S. military operations overseas. The Obama administration quickly made public details of the operation that resulted in the killing of Osama bin Laden in Pakistan in 2011. President George W. Bush commissioned a bipartisan investigation that produced a public report describing the intelligence failures that precipitated the 2003 Iraq War.

Repatriating survivors raises questions

One of the strikes raises particularly thorny questions about the legality of the current U.S. conflict.

On Oct. 16, Mr. Trump announced that there had been a strike on a semi-submersible boat in the Caribbean. Four “narcoterrorists” were targeted, but two survived. The survivors were soon repatriated to their home countries of Ecuador and Colombia “for detention and prosecution,” according to Mr. Trump.

It appears unlikely that either man will be prosecuted in his home country, however. And the speed with which the U.S. surrendered the two survivors also casts doubt on the administration’s contention that America is at war with drug cartels, according to Professor Corn.

“In what war do you capture enemy operatives and send them home?” he says.

The episode suggests an administration that believes it has enough evidence to justify killing people in international waters, but not enough evidence to prosecute them in court, says Professor Ingber.

“If we had clear evidence of a crime – the kind of evidence of terrorism that would suffice to target and kill these individuals – we would [detain and] prosecute them. The president chose to do neither of those things,” she adds.

“That suggests to me that at least some voices inside the administration are aware that their legal theories would not hold up in court.”

It’s also unclear exactly what a “narcoterrorist” is. Terrorist groups are typically defined as having political motivations, whereas cartels are driven by the desire to make money. There’s also the fact that only small amounts of fentanyl, which Mr. Trump has repeatedly said has been on targeted boats, are smuggled out of South America.

“Eroded” guardrails

Voices raising concern over such issues would usually come from the army of lawyers working on military operations at the Pentagon and the White House.

But earlier this year, the Trump administration fired senior military lawyers, known as judge advocates general, serving in the Army, Navy, and Air Force. The administration has made similar dismissals of perceived anti-Trump lawyers and agents at the Department of Justice and the FBI. After the JAG dismissals in February, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth told reporters he didn’t want the lawyers to pose any “roadblocks to orders that are given by the commander in chief,” Military.com reported at the time.

Yet roadblocks are what JAGs are supposed to provide when the president issues a legally questionable order to the military, experts say.

The administration “wants [lawyers] who have to prove their political fealty to the president,” says Professor Corn.

They appear “to have set the conditions for a lack of criticism of its views within the system,” he adds. “The traditional guardrails have been eroded.”

In recent decades, these checks inside the executive branch have become the primary means of ensuring the president is using war powers lawfully, experts say. Courts in recent decades have backed Congress in giving broad deference to the president in military affairs. While the Constitution grants only Congress the power to declare war, legislators haven’t formally done so since World War II. A broad resolution the House and Senate passed authorizing the use of military force after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, is still in effect, but it’s been criticized as giving too much discretion to the president and lacking oversight mechanisms.

The Republican-controlled Senate voted largely along party lines last week to block a resolution that would have required congressional authorization for a U.S. strike on mainland Venezuela, though some Republicans have joined Democrats in asking the administration to give more details about the legality of the strikes. Trump administration officials told Congress last week that they had no current plans, or legal justification, to launch land strikes against Venezuela, CNN reported.

The United States has embraced a more ambiguous and open-ended approach to warfare since 9/11, as its enemies have shifted from sovereign nations to include more stateless and covert organizations.

While this has siphoned more power toward the president, supporters say it’s necessary to react to a more fast-moving threat landscape. Critics say it has given the president too much power and has led the U.S. into expensive forever wars that alienate some Americans and U.S. allies.

Professor Corn is in the first camp. He was an early and strong supporter of “a very pragmatic interpretation of armed conflict,” he says. He agrees with the administration’s decision to label drug cartels as foreign terrorist organizations.

“And good on the president for being more determined to interdict the flow of illegal narcotics,” he adds.

But, he notes, this expansion of counterterrorism criminal laws does not indicate nor justify the assertion that the U.S. is in an armed conflict with these groups.

“When the nation orders members of the armed forces to engage in lethal conduct, they have a right to expect legal and moral clarity, and I don’t think they have that now,” he says.

“That’s tragic, because somebody’s got to issue the order to attack, and somebody has to pull the trigger and watch the result. And they’ve got to live with that the rest of their lives.”